The Correlation Between Poaching and Culling

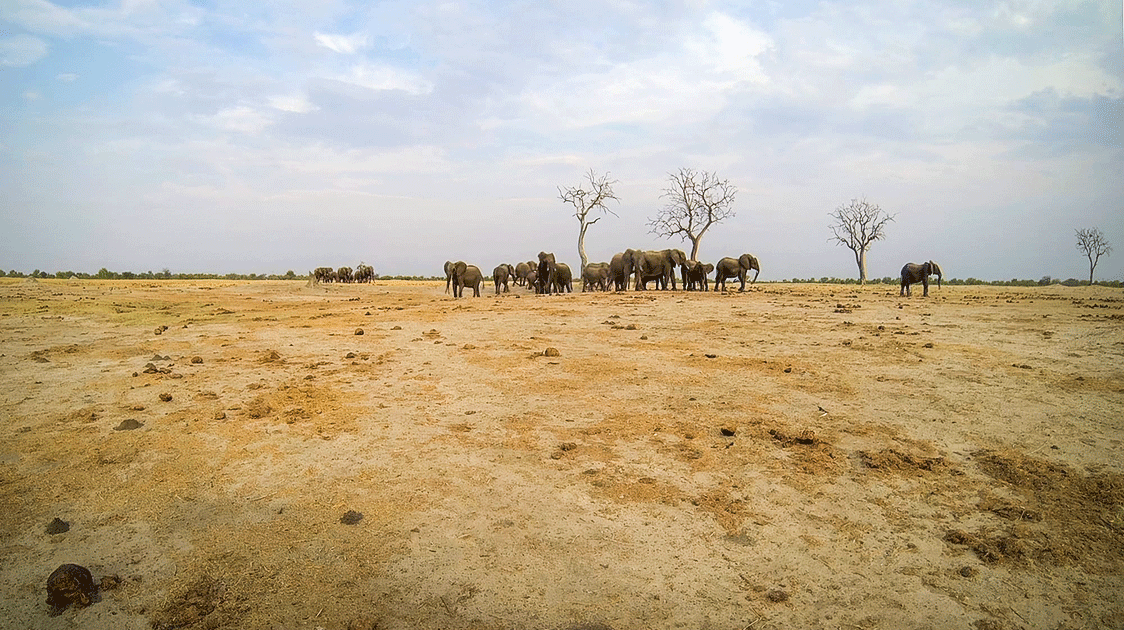

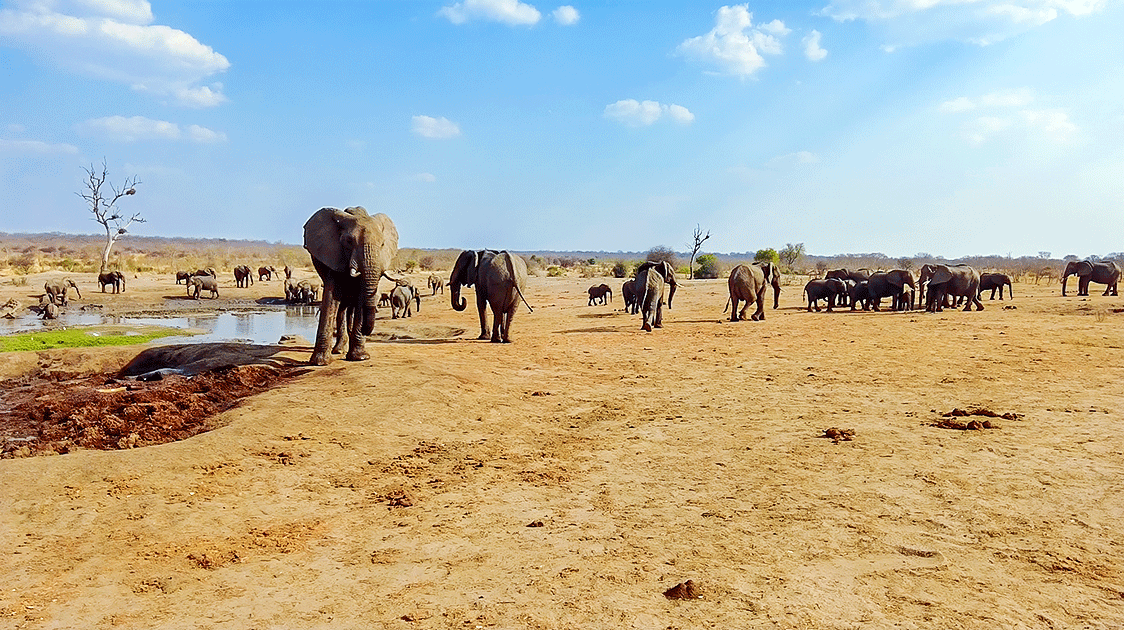

When Ted Davidson, the park's first warden, arrived in Hwange in 1922, he realized that the provision of water was the key factor in the park's development. The region is semi-arid, with an average annual rainfall of around 25 inches, most of which falls between November and March.

By July each year, most natural waterholes dry up in all but exceptionally wet seasons. Water-dependent game animals were forced to leave the park, and conflict was inevitable with a rapidly increasing human population bordering the park.

Most of Hwange National Park is flat and sandy, with little run-off during the rains; consequently, there are no perennial rivers and very few small water- courses.

There are, however, numerous natural pans formed over thousands of years by animal activity. These pans are seasonal, only filling with the arrival of the rains.

The game park sits above a network of fossil riverbeds containing vast amounts of water, so a program was started to sink boreholes near established pans and pump water into them.

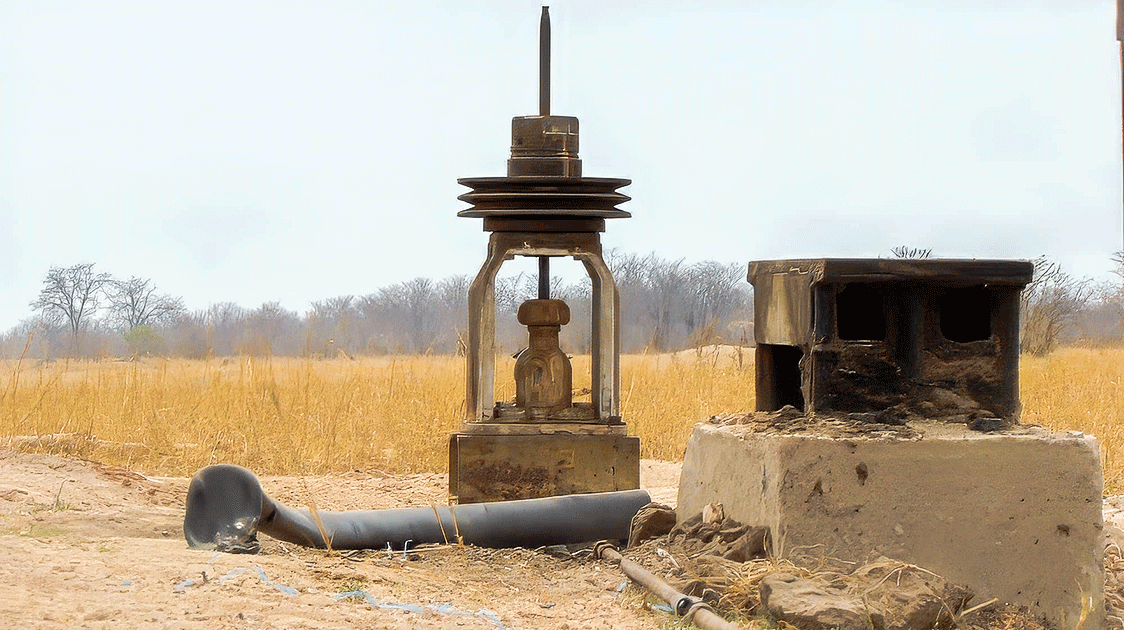

As wildlife populations expanded, elephants in particular, the water demand increased. The windmill system was unable to cope.

Diesel engines replaced windmills in the 1950s and 1960s, and the efficiency of the water supply system improved considerably.

The establishment of water points in Hwange National Park

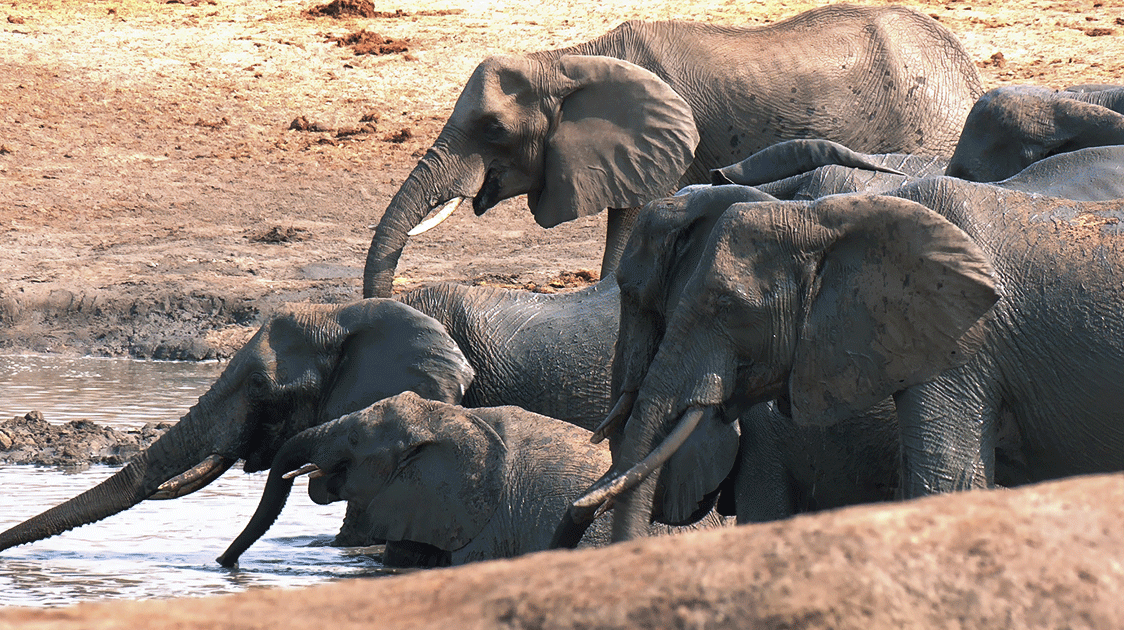

As water points multiplied and the park opened up, the animal population exploded, with elephants leading the way. With this increase, the damage to the habitat became all too evident.

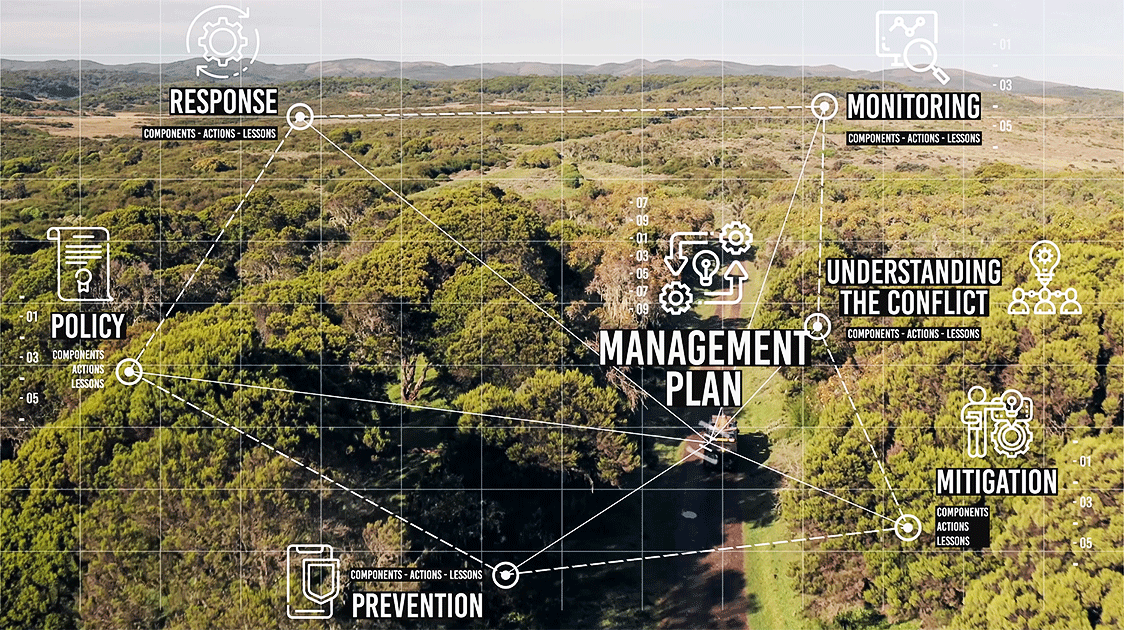

The authorities faced two alternatives: culling back the elephant numbers or letting "nature" take its course.

The stable limit cycle hypothesis is the widely quoted theory used to oppose culling.

This hypothesis can be viewed as a cyclical relationship in which elephant numbers increase while thinning out the forest and then decline when trees become sparse.

With the decline of elephants, the trees regenerate, and the cycle is repeated.

There is a time lag whereby elephants do not respond quickly to environmental change; hence, the trend of elephants and trees is like sine waves, with the trees' peak slightly ahead of that of elephants.

The Western World often portrays Kenya as the darling of African wildlife conservation because of its protectionist standpoint.

Kenya's Tsavo National Park is one of Africa's largest, extending over 5,300 square miles. In the late 1960s, the park faced a severe over-population of elephants like the one facing Hwange National Park.

The Kenyan authorities followed the stable limit cycle hypothesis and did not intervene. In this decision, however, significant factors that had created the problem were overlooked, and false assumptions were made.

Firstly, animal populations were confined within artificial man-made boundaries; it was not a "natural" situation. Secondly, early elephant counts in the 1960s were grossly inaccurate, representing less than one-tenth of the actual numbers.

The last absurd assumption was that dead bodies return much-needed elements to the soil.

In 1971, a severe drought hit the region, and as many as 15,000 elephants and hundreds of black rhinos in and around the park died of starvation.

People from the neighbouring villages, who were also suffering from the effects of the drought, swarmed into the park to gather up the ivory that littered the landscape.

Once people had picked up all the ivory, poaching was the natural progression. This spawned a pandemic that swept across the sub-region. By the 1980s, the elephant population in Tsavo had been reduced to 6,000 from an estimated 36,000.

The irresponsible decision to allow Tsavo to self-destruct resulted in the desertification of thousands of square miles of Commiphora canopy woodland.

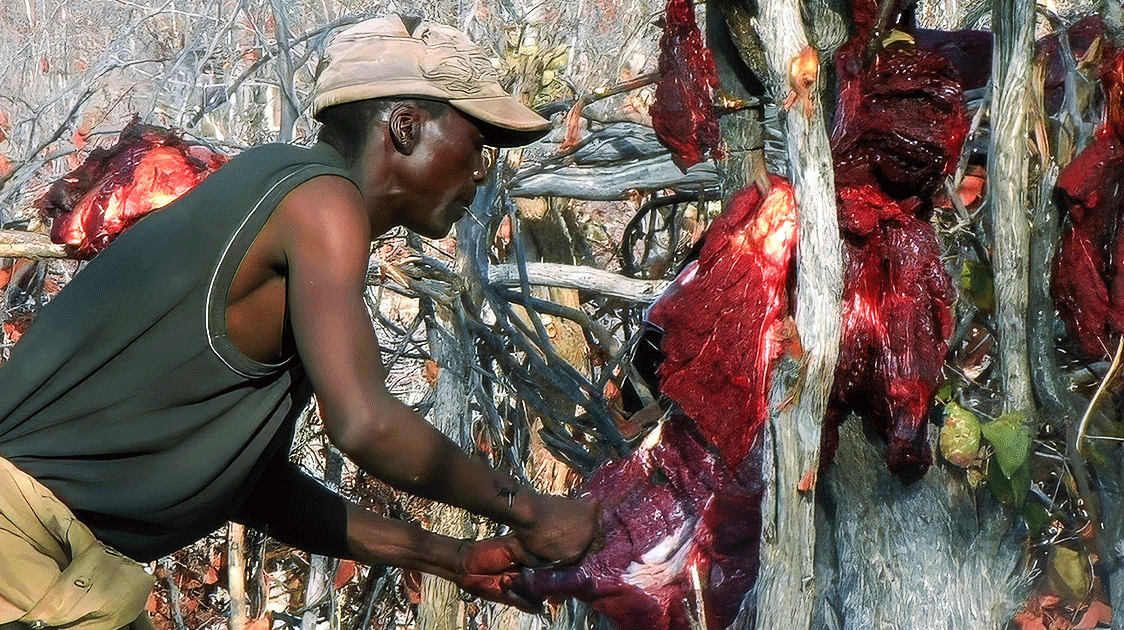

The Tsavo-type solution was unacceptable to the Zimbabwean authorities. Not only would the environment be totally destroyed, but it would also result in a waste of meat in a protein-deficient country, a loss in potential revenue from skins and ivory, and there was also the ethics involved in allowing animals to die of starvation.

Culling appeared essential to ensure the conservation of the elephants and the many selective grazers and savannah-dwelling species in the grasslands.

It was also considered that as the Hwange National Park was created through the artificial provision of water, it was not a natural environment and had to be managed.

Regarding the Zimbabwean Parks and Wildlife Act, the National Parks and Wildlife Management Authority protects all ecosystems and their components, not individual species. Consequently, a program to reduce elephant numbers was initiated.

For culling to be effective, more animals must be removed than are recruited into the population each year. It only takes around 15 years for an elephant population to double in size, so there is little risk of over–culling.

Hardwood woodlands, on the other hand, take ten times as long to recover from elephant damage and only then where the effects are reversible.

So even if a mistake was made in calculating the off-take, it would only take 5-7 years to substantially increase the elephant population, whereas it would take over 100 years for the hardwoods to increase.

Caution was exercised with the culling program in Hwange. From 1960 until 1970, only a few hundred elephants were eliminated yearly. In 1971 and 1972, two thousand elephants were removed.

Soon after, the program was stalled due to the country's liberation war. No major culls were carried out until 1980.

In 1983, the goal was to reduce the population from 23,000 to 12,000, the level at which severe habitat damage in the park first caused concern. This figure was calculated considering vegetation composition, food availability and climate.

It was acknowledged that even 12,000 elephants were too many, as the vegetation state in the 1960s had not been closely monitored, and considerable habitat modification had probably occurred before it was recognized as such.

Furthermore, when the population reached 12,000, it was already increasing exponentially, so fewer animals had caused the damage than reported.

The ideal situation would have been to reduce numbers below the ecological carrying capacity and then allow them to build back up. This was, however, logistically impossible with the limited resources available.

In 1980, there was a considerable backlog of culling throughout Zimbabwe and a lack of the essential equipment with which to do it.

With serious over-populations in a dozen different areas and knowing that as elephant numbers increase and resources decline, the rate of destruction accelerates, the authorities could only do their best.

The Hwange operation was staged over three years as it was impractical to cull and recover products from 11,000 elephants in a single dry season. Continued population growth during this period meant some 13,000 animals had to be removed.

The exercise was completed in 1987 but was hardly over before a significant influx of elephants from the seriously overpopulated Chobe National Park and adjacent areas in Botswana entered the park.

The 1987 post-cull census in Hwange returned over 17,000 heads and included recently tagged animals that had travelled over 100 miles from west of the Chobe National Park.

Since 1987, there have been no substantial elephant culls in Hwange National Park for various reasons.

The international ban on the sale of ivory has made culling prohibitively expensive. The cost of mounting a culling operation of 1000 elephants is around USD 300,000.

While some money can be recovered through the local sale of ivory, meat, and skin, the only way to recuperate a culling operation's expense is through the international sale of ivory or with foreign funding.

Since the elephant was listed on CITES Appendix I in 1989, two one-off sales of raw ivory have occurred. The first was in 1999, when Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe sold ivory to a single buyer (Japan), and the second took place in 2008, when Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, and Zimbabwe were sold to China and Japan.

Examination of the returns from the sales indicates that the range states lost between 65% and 75% of the value expected under normal trading conditions.

Nevertheless, the CITES standing committee verified that the sale proceeds were used for elephant conservation and community development.

The present decision-making mechanisms of CITES do not readily lend themselves to providing incentives to conserve elephants.

When Ted Davidson established the park in 1922, there were between 500 and 1000 elephants in Hwange. Today, the population has exploded to around 40,000 or 7.1 animals per square mile, unevenly distributed across an area covering 5600 square miles.

If a National Park aims to sustain woodlands and areas of 'old growth' to maintain the levels of biodiversity associated with it, then woodlands, which receive less than around 30 inches of rainfall per year, will likely decline or be lost at elephant densities even as low as 1.3 elephants per square mile.

If the Zimbabwean wildlife authorities had sufficient money, acted in defiance of world opinion, and started culling back the elephant population in Hwange, the result would be much the same as in the 1983 culling operation. Botswana, notably the Chobe Game reserve, is still critically overpopulated with elephants, and Hwange would again be swamped.

Providing year-round water to the Hwange National Park has created a water-dependent, artificial environment. This provision has triggered an unnaturally high population of elephants, which is destroying a delicate ecosystem.

Turning off the water supply will not solve the problem, as there would be a mass, uncontrolled die-off of most wildlife species, including elephants.

If water continues to be pumped and nature is left to itself, a disaster on a scale surpassing that of Tsavo National Park will result.

Control and management of elephant numbers, not only in the Hwange National Park but also in neighboring Botswana, is the only solution.

The elephant poaching scourge that is affecting parts of Africa and the over-population problem that faces Zimbabwe and Botswana can be directly linked to the ban on the international ivory trade.

Africa has been denied using an essential tool in its wildlife conservation toolbox.

Comments ()