Eating Til it’s All Gone???

By Hank’s Voice

Some critics of hunting assert that it should only be done for meat and that only indigenous peoples should be hunting, as they are true conservationists. But a 2016 paper by Ripple et al. published in the journal Royal Society Open Science presents concerns strongly suggesting such claims should be evaluated more critically, defined by legal vs. illegal, and properly addressed.

This summary was the first comprehensive global assessment of bushmeat hunting on terrestrial mammals. A surprisingly delayed treatise considering the seriousness of this subject, the level of which is summarized well in this direct quote, “Only bold changes will substantially diminish the imminent possibility of humans consuming many of the world’s wild mammals to the point of functional or global extinction”.

Their analysis showed that bushmeat hunting is a driver of a global crisis impacting 301 terrestrial mammal species threatened with extinction. Nearly all of these are in developing countries and are also threatened by deforestation, agricultural expansion, human encroachment, and competition with livestock.

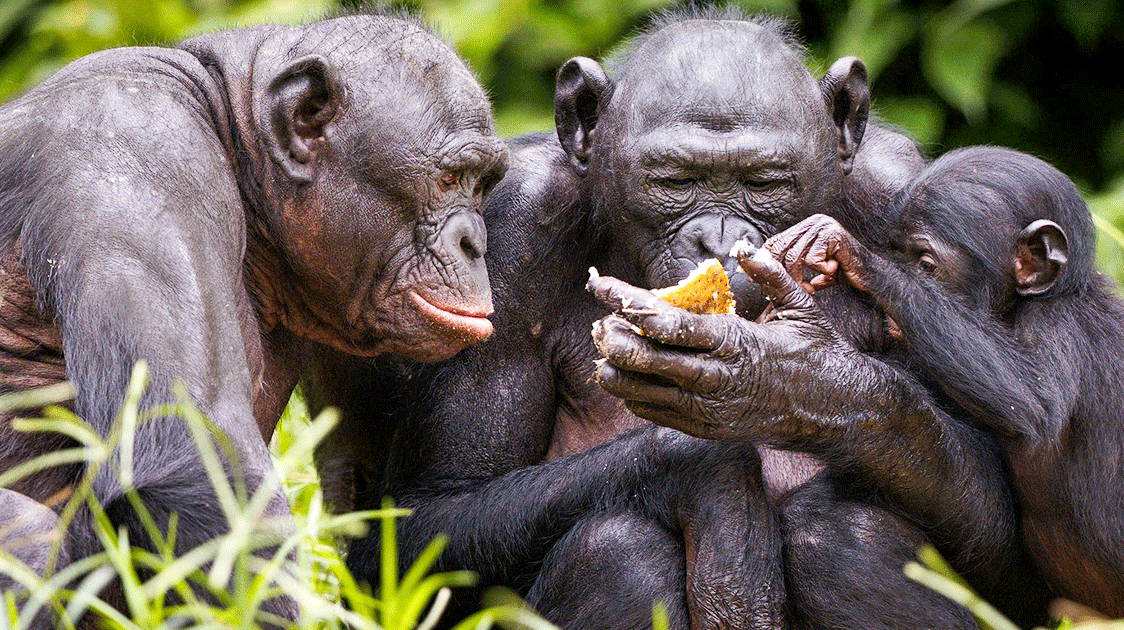

Orders with the most species affected are primates, even-toed ungulates, bats, diprotodont marsupials, rodents and carnivores. The regions with the most species threatened are Southeast Asia and Africa. Countries with the most endemics threatened are Madagascar, Indonesia, the Philippines, Brazil, Papua New Guinea, India, and China.

Only 2% of the species examined have populations considered stable or increasing. Between 1996 and 2008, the conservation status of 23% of heavily bushmeat-hunted species decreased (63 of 270 with data available). But 40 were already critically endangered by 1996.

The highest number of species declined was among primates and even-toed ungulates. Three species—the kouprey, Wondiwoi tree kangaroo, and little earth hutia—are possibly already extinct.

Bushmeat hunting affects 7% of all assessed terrestrial mammals and about 26% of all threatened terrestrial mammals on Earth, including 72 critically endangered, 114 endangered, and 115 vulnerable species.

And their habitats are threatened, too. Only 10.5% have ranges within protected areas, and 65 species range entirely outside protected areas. But protected areas too, are no longer any real guarantee of survival, as poaching pressures are increasing inside many parks and reserves, leaving empty landscapes.

Fencing areas as a potential solution has increased in the last few decades, but it also has problems: it restricts animal movements, decreases effective park sizes, and destroys ecological connectivity.

Bushmeat hunting is for both consumption and trade, is typically unsustainable, and is intimately tied to human development and food insecurity, emergent disease risks, and land use changes. And it absolutely must be distinguished from legal, regulated hunting which can be sustainable and of higher overall value.

It is also not a new problem but rather an accelerated one in many areas due to growing human populations, increasing trade, and widespread adoption of firearms and motorized transport, which increases efforts and spatial extent.

Left unchecked, it could result in the collapse of food security for hundreds of millions of people, and the vital ecological and socioeconomic services the affected species provide will be lost. Larger species are targeted first but are usually the least able to bear offtakes. Close to 60% of the largest threatened mammals weighing greater than 1000kg are at risk of extinction from human consumption.

No other taxonomic group contains terrestrial animals in the same size classes of large modern mammals, and their functional losses can rarely be compensated for, which leads to permanent ecosystem changes.

Large predators may have their prey bases depleted, and large-seeded plants may lose their necessarily large seed dispersal agents. Losing large herbivores also causes a systematic increase in the abundance of rodents, which excel at hosting and transmitting human-borne zoonoses.

Small mammals are also indispensable as they are the most documented frugivore seed dispersers. Removing them negatively affects forest regeneration and composition.

Although there may be an overlap in body size with birds and reptiles, their ecological roles are not always interchangeable. Bats especially fill very specific niches as specialized pollinators and seed dispersers. As such, they are unlikely to be replaced, yet they are the largest threatened group weighing less than 1 kg.

Significant, complex challenges exist, however, in addressing the bushmeat crisis. Many different ethnic groups are involved, as bushmeat is a cultural legacy for many, not just those who live rurally.

It’s also a delicacy or sign of affluence for city dwellers and expats. Food that is not always necessary for subsistence is lucrative commercially. Illegal, international trafficking is poorly monitored, even in developed countries such as EU nations.

Developed countries should be helping developing countries protect wildlife from such illegal, unsustainable use. The authors of this paper note that although several major summits on biodiversity conservation and protected areas, dating back to 1992, have been held, with developed countries committing to providing significant funding for biodiversity in the tropics, especially, little conservation progress has occurred, and unfulfilled promises remain.

Multinational companies extracting natural resources in developing countries should also accept responsibility for and properly address their impacts. Their activities often increase access to wildlands and wildlife, facilitating new non-subsistence hunt impacts and/or exacerbating preexisting ones.

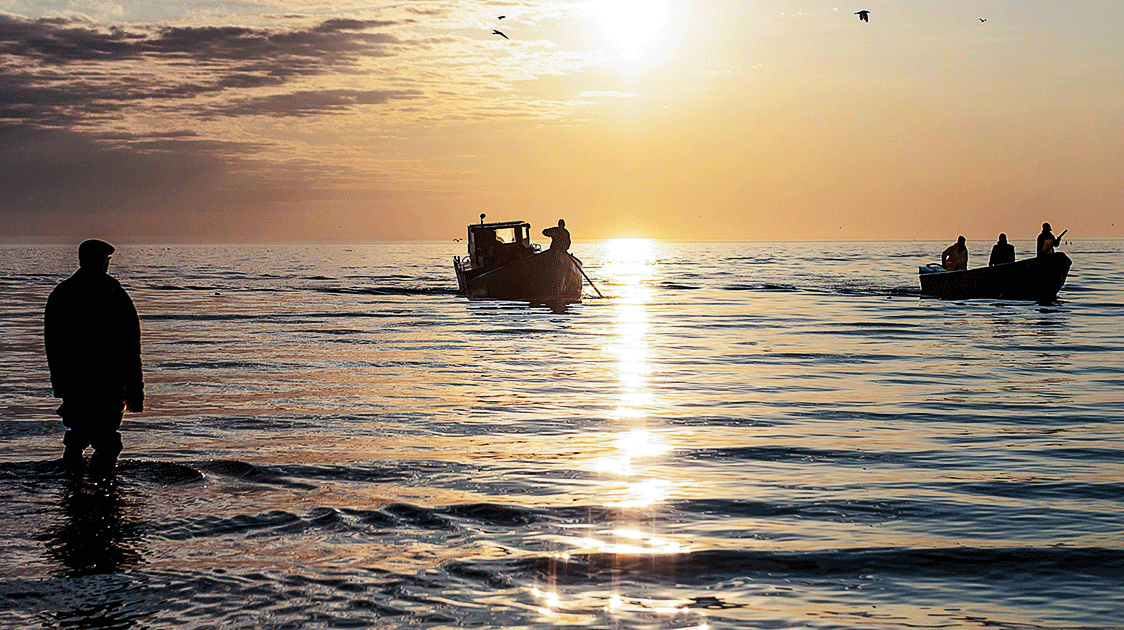

The authors of this paper offered the example of how the explosive increase of non-domestic (e.g. heavily subsidized by the EU) fishing in African waters appears to be an unexpected driver of the bushmeat crisis by forcing locals to depend on terrestrial bushmeat instead of their historically more sustainable marine resources.

Effective conservation, of course, is most readily accomplished when people have both food and income security. But in the case of bushmeat, the authors of this paper suggest that aid and transitions must be careful. Ensuring current food security without changing hunting practices won’t solve the bushmeat crisis.

Only a few hunters can be very effective, can migrate to hunt other areas, or switch to less preferred species. Tourism, via both safari hunting and photography, are suggested conservation tools that, properly done, can give wildlife higher value when utilized legally and regulated.

They also urge that science must provide a better platform for decision-making. Even simple data like basic biology and evaluation of the remaining numbers of affected species are needed.

And although the general public prefers charismatic large animals who, in turn garner more attention from researchers, ground-level data is needed for rates of harvest for all species. More research is also needed in Southeast Asia, which is the area most impacted but with the lowest number of publications.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, the following quote suggests that more cross-disciplinary exchange is needed to solve wildlife problems that are people problems, too:

“Good conservation paradigms cannot be built only on ecological understanding; they require a sophisticated evaluation of the drivers of human behaviour and insight and innovation as to how that behaviour may be changed.”

Indeed.

Interconnected, cascading chains of events and interactions requiring solutions not dissimilar in basic structure to the problem itself.