Free-market Environmentalism: The USA Versus Africa

By Zig Mackintosh

The Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), based in Bozeman, Montana, USA, is a conservation and research institute dedicated to free-market environmentalism. PERC is committed to working with conservationists, policymakers, scholars, and journalists to understand the root of environmental conflict and move toward innovative solutions.

Their particular interest is in how markets encourage cooperation instead of conflict over natural resources and how property rights make the environment an asset by giving owners incentives for stewardship. The idea is to nurture a culture of creative conservation and environmental entrepreneurship to replace the often ineffective and acrimonious political culture; the ultimate aim is to improve environmental quality.

CNN founder Ted Turner's 113,000-acre Flying D Ranch, just outside Bozeman, is an example of environmental entrepreneurship in action. Turner bought the ranch in 1989 and was determined to rewild it, replacing cattle with bison. In the USA, there are two classifications of bison: conservation herds, considered "wild", and commercial herds, considered "domesticated." Approximately 30,000 wild bison live in conservation herds, and around 500,000 bison live in commercial herds.

Harvested game meat in the USA, except for bison and alligator, cannot be sold. The commercial bison business started in the late 1960s, but it wasn't until the 1980s that the industry gained momentum. Today, there is a high demand for bison meat, a motivating monetary incentive without which Turner may not have invested in Flying D Ranch and his rewilding project.

Today, Turner is the second most prominent landowner in the USA, owning around 50,000 bison on ranches throughout the West. His restaurant chain, Ted's Montana Grill, serves buffalo burgers, ribeye steaks, and other bison meat dishes and is expanding nationwide.

Brucellosis is a bacterial disease capable of devastatingly affecting bison, cattle, and elk. In 2009, Turner Ranches agreed to hold a quarantined herd of 86 bison from Yellowstone National Park for five years for monitoring in exchange for 75 percent of the herd's offspring to offset costs.

The animals were kept on a 12,000-acre paddock separate from the resident ranch bison. As a result of this partnership with Yellowstone, Turner now owns one of the only privately held herds of Yellowstone bison, thought to be the gold standard of bison genetics.

So, what do PERC and Ted Turner's bison herds have to do with Africa and its wildlife?

Southern Africa embarked along this environmental entrepreneurship road in the 1960s thanks partly to the research of two American Fulbright scholars, Dassmann and Mossman.

The Henderson brothers commissioned them to assess the feasibility of marketing the meat from harvested wildlife without decimating game populations on their Doddiburn Ranch in the southwest Lowveld region of Zimbabwe. The researchers' conclusive results showed that wildlife was a better economical land-use option than cattle, especially in semi-arid areas.

The concept gained little traction mainly because private ownership of wildlife was not permitted. The revolutionary Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975 changed this and gave the landowner ownership of the game; he could now benefit from the resource.

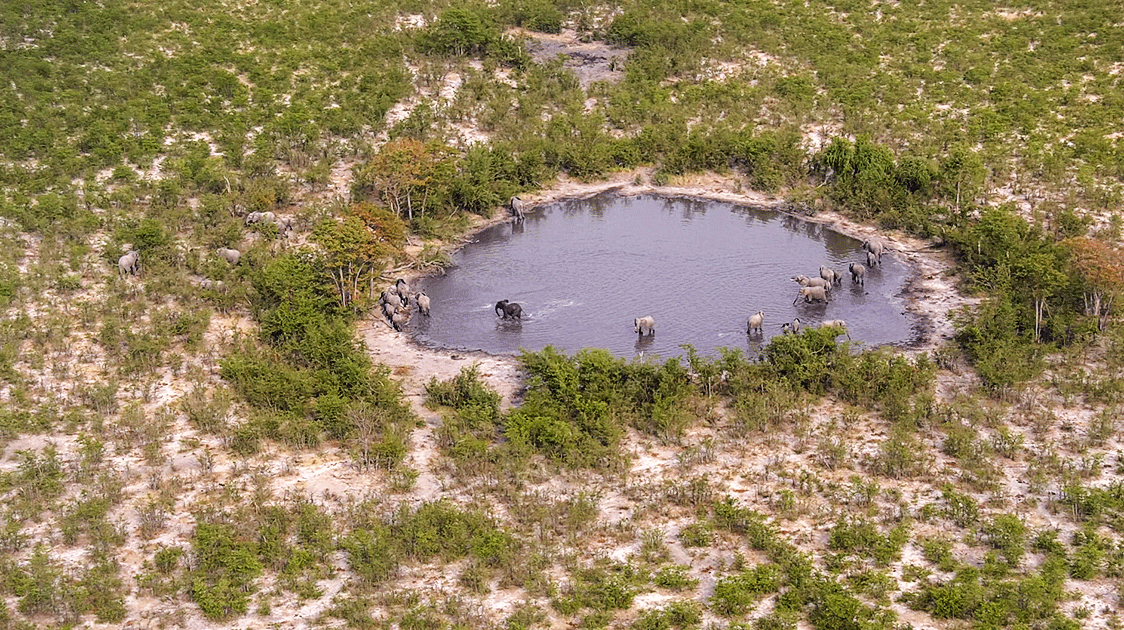

Between 1975 and 1989, the amount of land in Zimbabwe devoted to wildlife increased by 62%, from 59,700 to 97,000 hectares, a direct result of the new act. At that time, there was little safari hunting activity, and the emphasis was on cropping animals for meat sales.

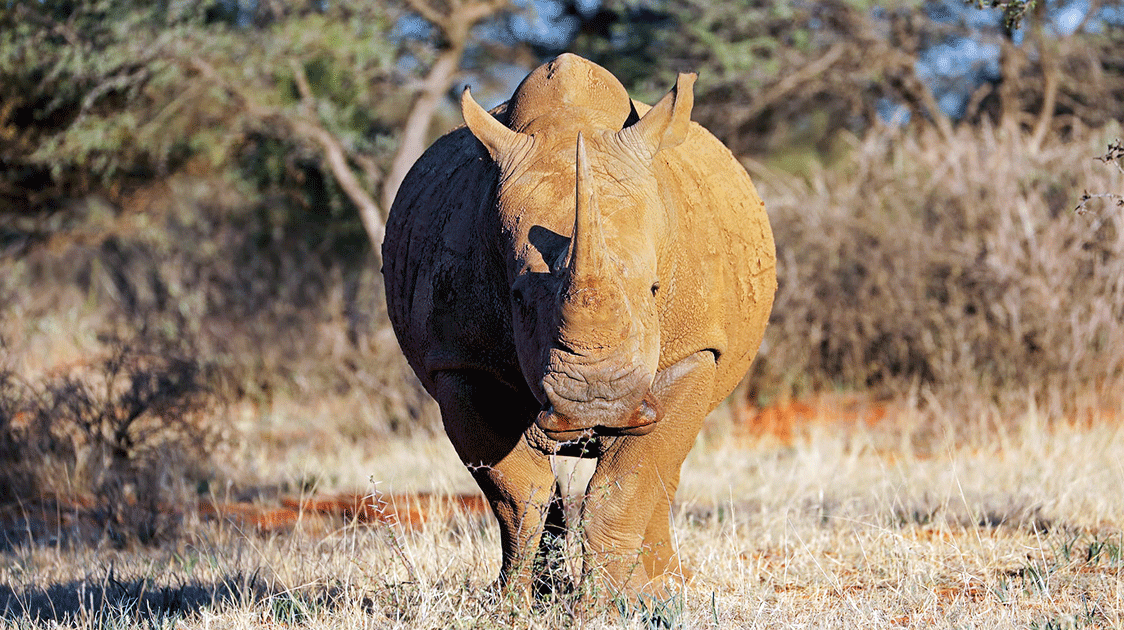

Things were also changing in South Africa. Faced with an overpopulation of white rhinos in the game reserves, the Natal Parks Board decided to allow private ownership of the species.

The landowner could profit from his investment through photographic and hunting safaris and selling excess animals to other game ranchers. The transfer of ownership handed the private landowner the responsibility for the species' survival through protection from poaching and the provision of suitable habitat.

The rhino's range was extended, and the burden and cost of rhino protection shifted from the government to the private sector. By auctioning off excess rhinos from parks approaching maximum carrying capacity, the authorities can ensure that breeding performance is not depressed through overpopulation.

Money realized through the sale of these animals is plowed back into the organization for use in other conservation projects. This radical concept of private rhino ownership was the engine that drove the establishment of game ranching in South Africa.

During the mid-1980s, the safari hunting business started to grow in Zimbabwe, an upshot of the hunting bans in Tanzania and Kenya. It became apparent to the Zimbabwean wildlife authorities that the same model of wildlife ownership enjoyed on private land could be extended to rural communities.

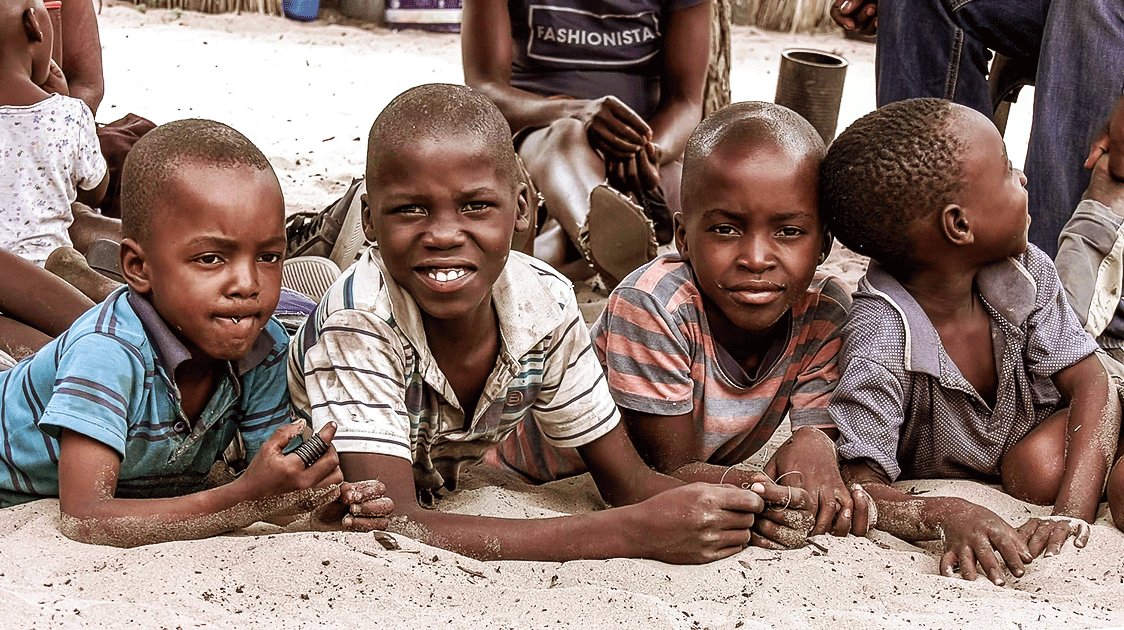

Campfire is the acronym for the communal areas management program for indigenous resources, a strategy devised to satisfy the needs of rural communities while conserving the environment.

The policy gives these societies the right to decide how - and whether- they want to conserve wildlife and habitats and the ability to benefit from them if they do.

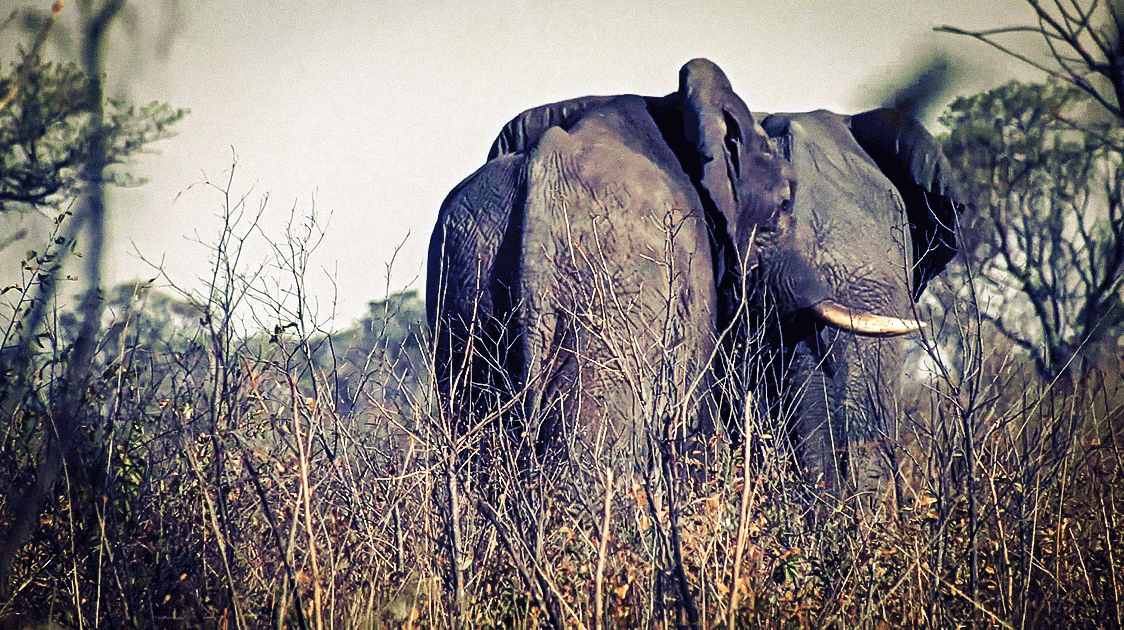

Safari hunting is the best wildlife use option in communal areas. Game populations are generally too low to support photographic safari operations but high enough to sustain controlled hunting.

Most safari hunting opportunities in communal lands are for dangerous game, the majority of which are considered problem animals, such as crop raiders like elephants and livestock-killing predators.

Trophy hunting benefits these communities in three ways.

The primary benefit is the revenue raised through trophy fees on the animals. The amount paid to District Councils averages $15,000 per elephant, constituting 95% of the total CAMPFIRE income.

The second benefit is the actual control of the problem animals, and thirdly, the meat from the hunted animals is distributed to the community.

An ancillary spin-off is an opportunity for employment within the hunting operations and curios production.

The local district council, not the central government, controls the revenue earned through sport hunting.

The people decide on how the money is used, whether in the form of cash dividends, infrastructure development such as wells, grinding mills, schools, and clinics, or compensation payment for damage by wildlife to crops and livestock.

Every major Zimbabwean national park has at least one boundary with a communal land. Communities in these regions have set aside areas along these boundaries for wildlife. This affords wildlife an extended habitat and creates a buffer zone between the people and the national parks.

Human encroachment on protected wilderness areas is held in check. The advent of Campfires has made wildlife valuable to the community, and pressure on individuals not to poach has increased significantly.

Free market environmentalism is alive and well in Southern Africa and has been extended to include rural peasant communities. The commercial use of wildlife products is not limited to a couple of species, as is the case in the USA. There is much that PERC and the United States conservation authorities could learn from the models that have been tried and tested in Africa.

(Zimbabwean native Zig Mackintosh has been involved in wildlife conservation and filmmaking for 40 years. Over the years, he has traveled to more than 30 countries, documenting various aspects of wildlife conservation. Sustainable use of natural resources as an essential conservation tool is the fundamental theme in the film productions he is associated with.)

Comments ()