Getting Shafted, Left, Right and Center

By Prof Brian Child

Most rural people in forests and drylands have insecure land rights, especially in Africa.

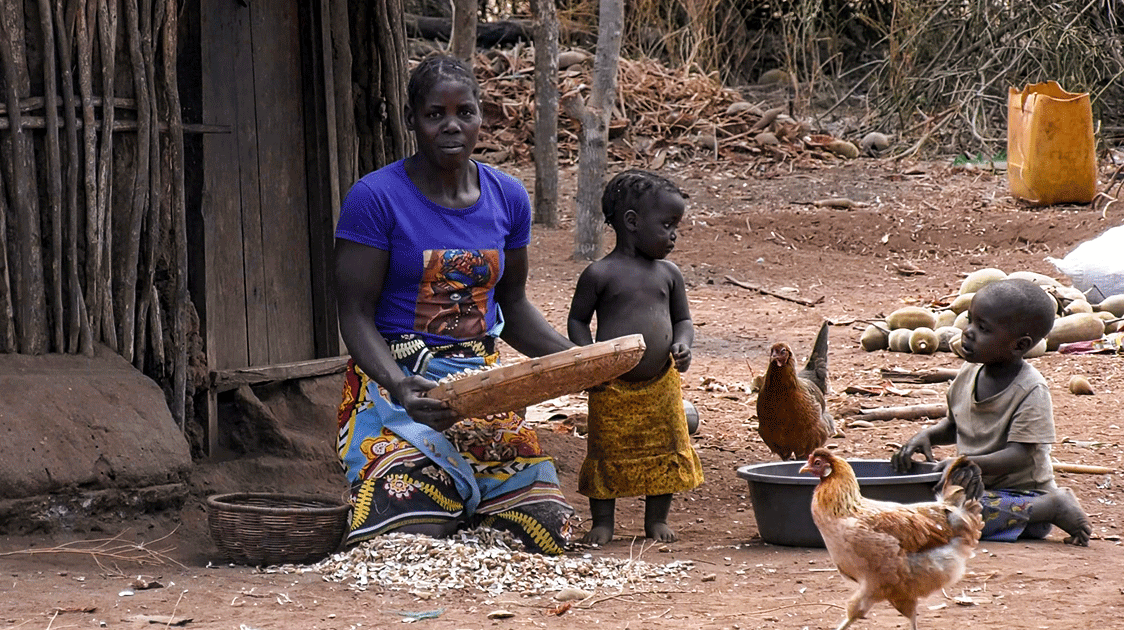

The perpetuation of so-called communal land is a tragedy, holding people in neo-feudal conditions, where the land is owned ‘on their behalf’ by the state, and they are the ‘subjects’ of traditional leaders who allocate land at the local level and to whom they are beholden for their homes and farms.

Politicians and officials support such ‘traditional’ systems despite their problematic social and economic consequences and are wide open to abuse, corruption, and resource extraction.

Pre-colonial land ownership in Africa was fluid, with few examples of formalized individual or group tenure, the primary designation being tribal territories and kingdoms.

Low populations and old and infertile soils meant Africans moved to new places once the land was used up; it wasn’t worth fighting over. Reader (1999) compared the ancient graveyards of Africa, which contain few signs of violence, with the history of Europe, which is brimful of castles, battles, and skirmishes as kings, dukes, and lords protected their high-value land.

Indeed, Reader speculates that conflict in Africa was relatively rare until the European and Eastern slave trade set people against each other. In the early colonial period, Africans were often consigned to ‘native reserves’ or ‘tribal trust lands’.

A few were created to protect local people from colonial exploitation. Still, most served to subjugate Africans and, to this day, facilitate the extraction of wealth by the modern economy and elites without proper recompense.

An example from South Africa, although a particularly egregious situation, illustrates the nature of the political forces and economic consequences at play in the perpetuation of communal lands. Communal lands were an instrument of oppression and extraction, but they remain ubiquitous in Africa (and beyond), holding in place a quasi-feudal system of governance.

Unfortunately, non-ownership of land was reinforced in the post-independence socialist period, while in many countries, control over wild resources was further centralized.

In the Republic of Congo, for example, age-old local systems of local forest management and communal territories ended abruptly in 1963 when all land was nationalized under the guise of scientific socialism.

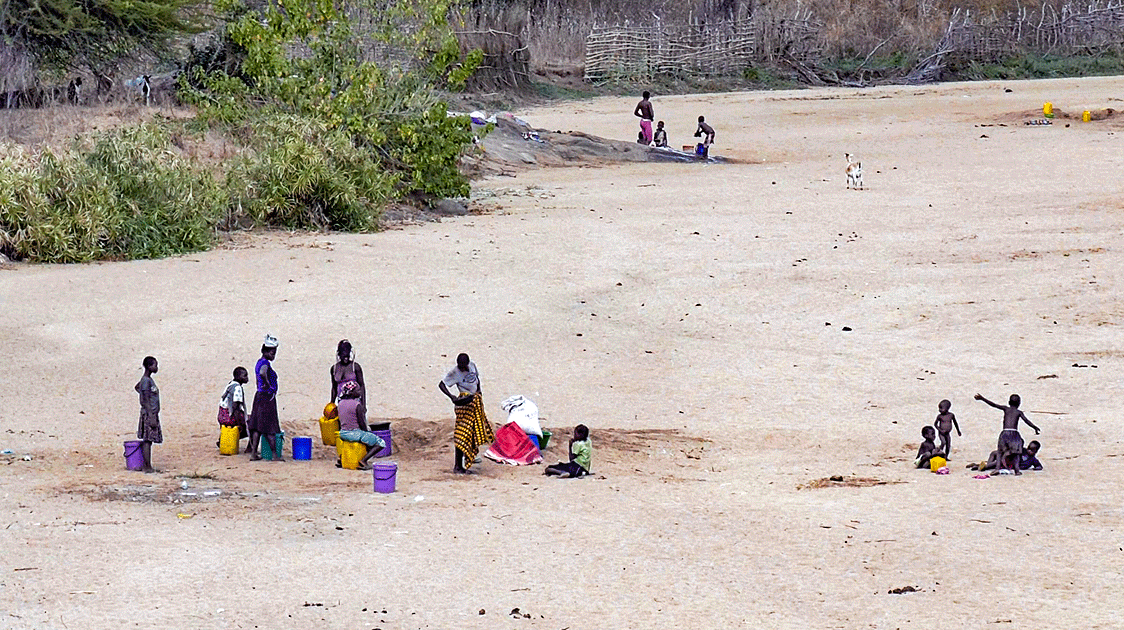

Even today, only 10% of rural land in Africa is registered, leaving undocumented and informally registered land susceptible to land grabbing, expropriation, and corruption.

Over 99% of forests and a similar proportion of drylands remain ‘communal’.

Good traditional management does exist, and some local leaders are exceptional. The system may even have been reasonably effective when populations were low and land was plentiful.

However, the opportunity costs of communal lands increase exponentially with human population growth and globalization. Communal lands are usually associated with hierarchical and personalized governance and dualism in which the elites have property rights, but the poor do not.

Modern title trumps local ownership rights, opening the door to corrupt elites and even outsiders to grab and sell off land that does not really belong to them.

The outdated institution of communal lands exacerbates poverty, environmental degradation, and the scourge of land-grabbing.

Owned by no one, they exemplify the persistence of bad institutions. Although they have not adapted to the rapidly changing circumstances of the 20th century, replacing them is controversial.

There is a strong attachment to the ‘traditional’ concept of non-ownership of land, especially by people in power who benefit from the system.

Poverty remains despite the economic consensus that persistent rural poverty can only be addressed if the fundamental failures in property are rectified, including titling individual farmers in productive areas or a more sophisticated combination of personal and village-based tenure in forests and drylands.

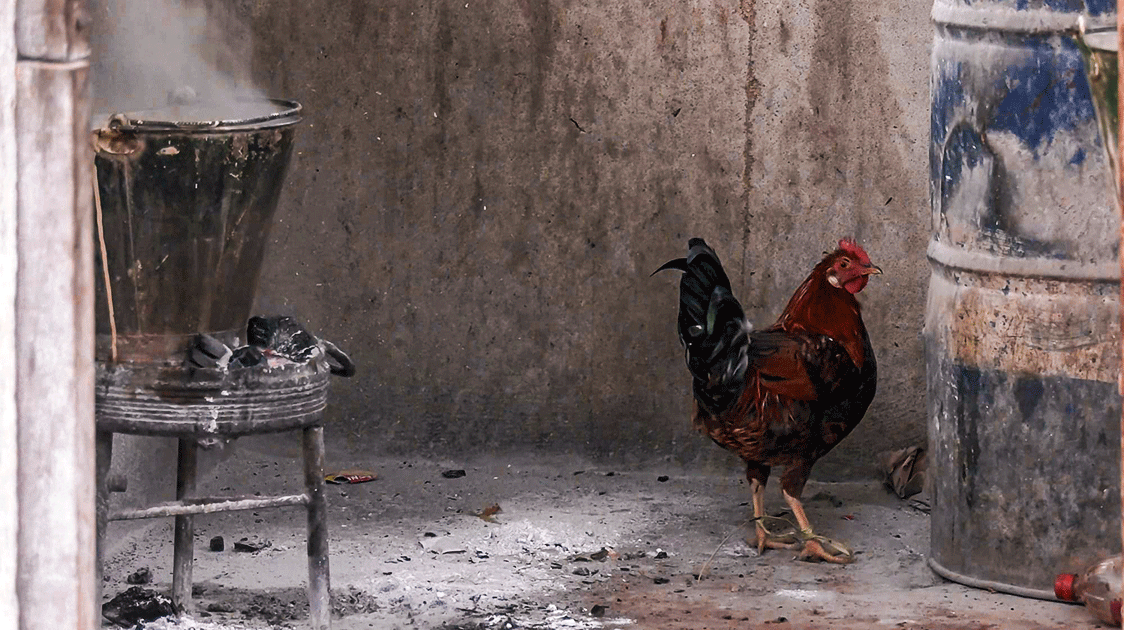

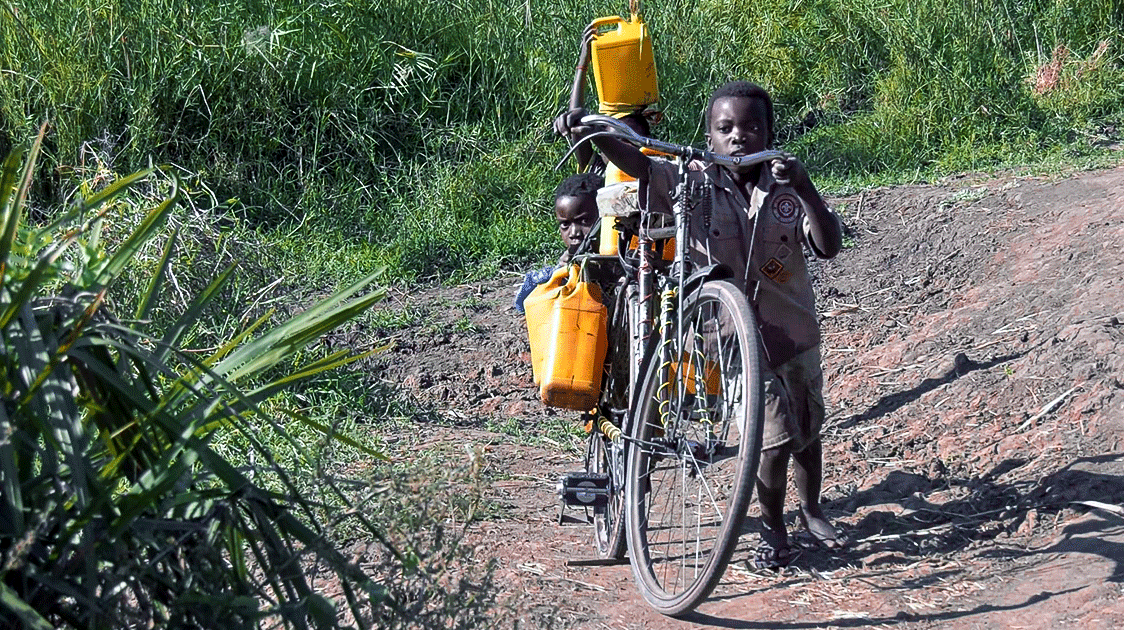

If land rights are weak, local rights to forests, fisheries, wildlife, and other wild resources are even weaker. People have few rights to wildlife or forests, so they use domestic crops and animals (which they do own) to exploit unowned land and grazing.

These diametrically opposite systems governing domestic and wild species have massive consequences, including on the managerial norms of state agencies. Thus, agricultural ministries encourage local people to improve their farming, while wildlife agencies do the opposite.

Claiming ownership of forests and wildlife, they seek to prevent communities from using them, sometimes even criminalizing age-old hunting-and-gathering livelihoods. They also claim most or all the income streams when these resources are exploited commercially (usually by outsiders), resisting the return of benefits to the communities that live with these wild resources.

Even when wildlife benefits do reach communities, officials expect them to be used for public amenities like schools or clinics. In contrast, agricultural profits are perceived as private income, benefit people directly, and are seldom taxed in this way.

The economic playing field is tilted dramatically against wild species, resulting in a highly dysfunctional political economy for them. Communities do not own wild resources and are disengaged from solving sustainability problems.

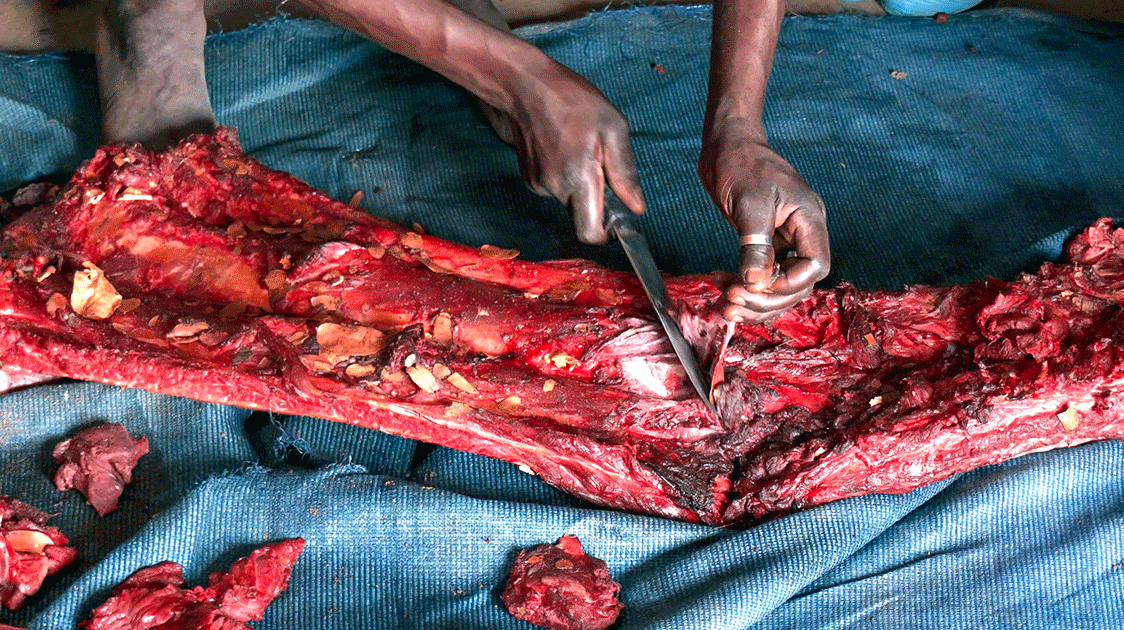

Forest communities in Congo, for example, were fully aware that overuse of bushmeat was threatening a major part of their livelihoods and were remarkably prescient about the causes of these problems.

However, when asked why they were not acting to save their own livelihood options, they simply said, ‘This wildlife is not ours’, leaving all responsibility for fixing the problem to the government despite knowing full well that the government lacked this capacity.

Even where local people have the right to pursue ‘subsistence’ uses, they are trapped in low-value commodity production (i.e., meat) because they are prohibited from undertaking active management or participating in the exchange processes that can add so much value to wild resources.

Local people consistently say it is ‘the government’s wildlife, and therefore it is the government’s responsibility to look after it’.

However, the effectiveness of public management relies on voluntary observance of rules of use because it is prohibitively expensive to impose and enforce rules through policing and punishment.

However, conservation rules in the tropics lack legitimacy. Local people continue to be excluded from making the rules and perceive conservation rules as privileging national or global users over local ones.

Westerners sometimes find it difficult to understand that de jure rules with no de facto legitimacy will simply be ignored, but in many disenfranchised communities, the norm is for everyone (including criminals) to exploit wild resources before someone else can, with use also exemplifying everyday forms of resistance and protest and ‘the weapons of the weak’.

Officials and attendees at lofty meetings may fantasize that they are making rules, but for all intents and purposes, wild resources remain ungoverned. Without recognized property rights, a genuine stake in the forests, wildlife, or fish they live with, and participation in conservation policy, these policies lack local social legitimacy and economic integrity and will continue to fail.

This contrasts starkly with the North American public model, where people have long participated in the process of making conservation rules, which are aligned with the public good and adequately funded.

Local people have clearly lost their rights to use wild resources. However, they have also lost their rights to valorize these resources in legal markets, reflecting the antimarket norms established by Roosevelt and colleagues in the 1900s and perpetuated by special interest groups today (through global institutions such as CITES).

Taking rights away from people without their participation, consent, or compensation undermines their livelihoods and might even be called theft.

These high-handed decisions cause considerable anger and resentment, illustrated vividly in interviews with Scottish fishermen in the 1990s when Africans proposed listing the North Sea herring on CITES to make precisely this point.

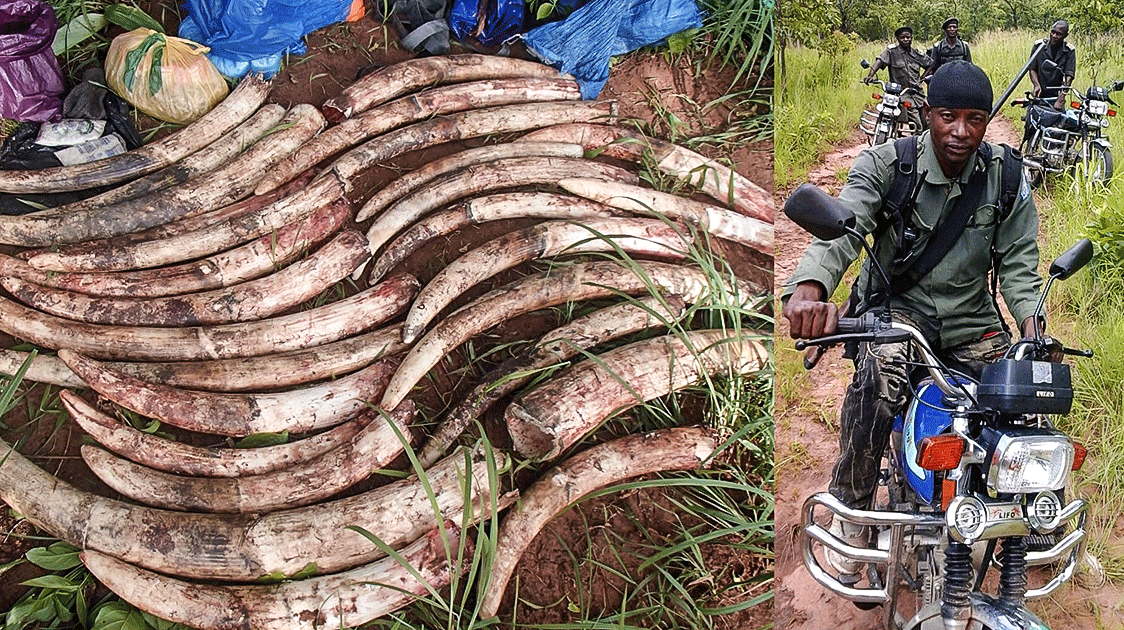

As with the prohibition of alcohol and drugs in the USA and bans on trade in 17th-century Europe, the overriding effect of bans is to shift use into the shadows and into the hands of criminals, stoking violence and criminality with serious social consequences for vulnerable people.

Removing the legal value of wild resources to local people removes any incentive to reinvest in them. This is a significant factor in the widespread loss of wild species across the planet.

Moreover, trade bans impose considerable opportunity costs on producer communities, given that the illegal trade in bushmeat, forest products, and high-value items like ivory, rhino horn, and abalone (excluding fish and forest products) is worth more than USD 8–10 billion.

The unthinking reflex of shutting down wildlife markets requires critical examination. Taking away rights from the world’s poorest people without compensation is legally and morally problematic.

By preventing the full economic value of the wild resources from being included in land use decision-making, it undermines the opportunity for local people to play a positive role in conservation. At the same time, it inflicts criminality on vulnerable people, including criminalizing age-old livelihood practices.

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)

Comments ()