Is Uncontrolled, Unregulated Gold Mining a Form of Poaching?

By Zig Mackintosh

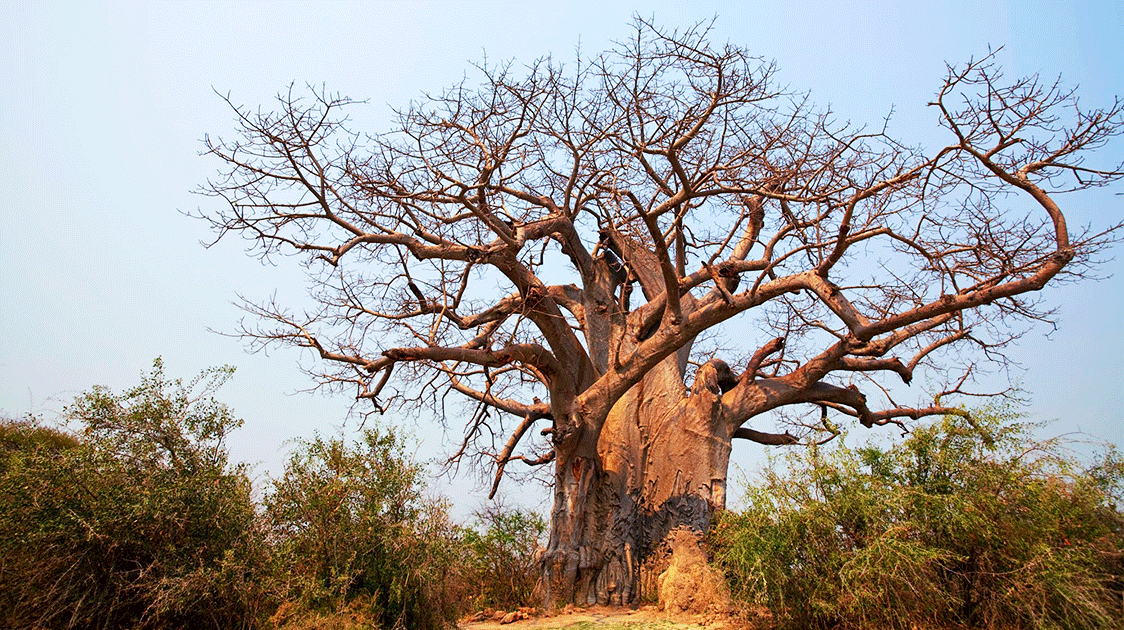

"Illegal" mining across Africa is a serious environmental concern. The Zambezi Valley in Zimbabwe, rich in gold deposits, particularly along riverbeds, attracts opportunist miners and organized syndicates.

Unemployment, poverty, and rising global gold prices are the main drivers for the practice, which is often associated with violence, unsafe working conditions, and exploitation of vulnerable groups like women and children. Deforestation, soil erosion, and biodiversity loss threaten the valley's ecosystem.

On the border of the Kruger National Park, zama-zama ("to take a chance" in Zulu) miners make enough money to afford to place orders for specific animals from poachers.

Entrepreneur and conservationist David Gunde and his company, Vinson, are driving the Coutada 7 wilderness restoration scheme along the banks of the Zambezi River in Mozambique.

While on location filming a documentary about the project, we stopped at a ramshackle gold mine on the banks of the Tsidze River, which flows into the Zambezi River.

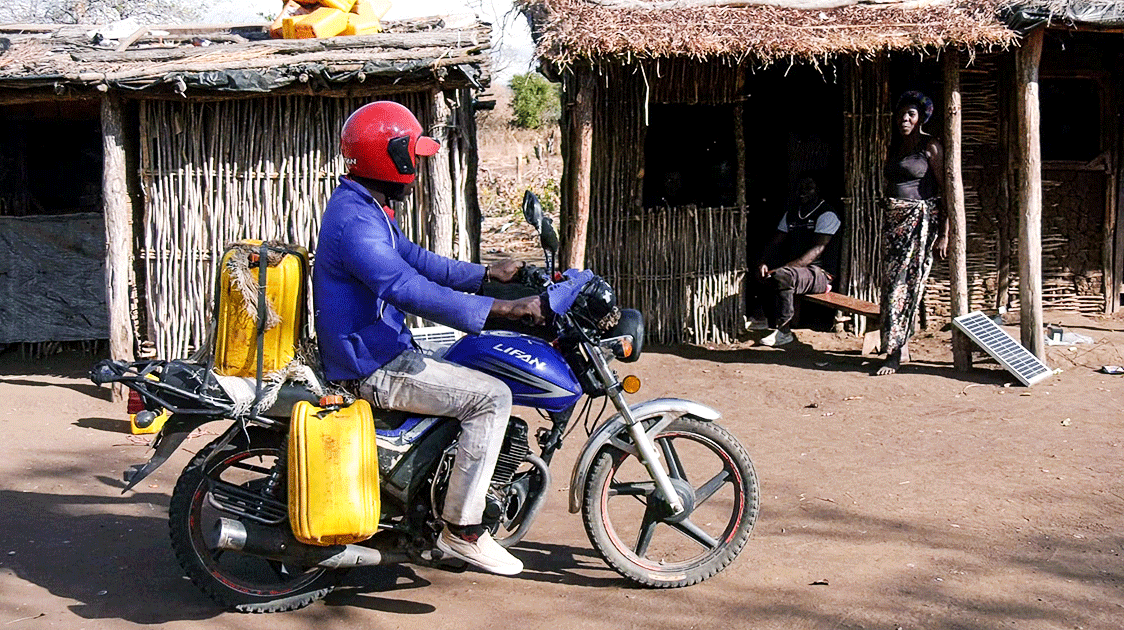

The miners have settled in the area with their families, and a small, makeshift village has mushroomed. There are a couple of tuck shops selling the essentials, a fuel supply shop, a clothing store, vendors hawking peanuts, a restaurant, a bakery and even a beauty salon. Gold dealers visit regularly to buy at source.

The makeshift mining village has all of the essentials

We arrived at lunchtime and ordered chicken and sadza (stiff maize-meal porridge) from the restaurant. Food is served fresh here, so it took some time for the cook to catch the squawking chicken darting between the huts, pluck it and throw it on the fire.

While this was happening, we visited the mining operation about 500m away. I expected to see a couple of guys panning the Tsidze River for alluvial gold but was surprised to see a massive, open-pit excavation operation.

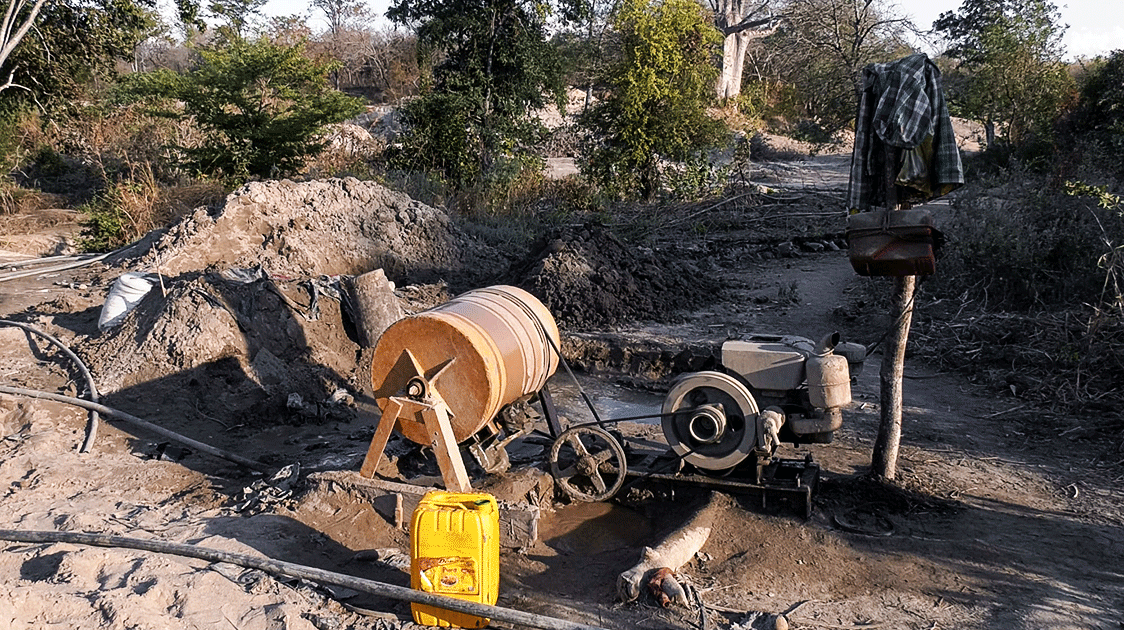

In some places, deep holes have been dug into the riverbanks, going down perhaps 100m or more horizontally. The rocks are shoveled or carted up to the surface by hand, put through a hammermill and crushed into sand.

The sand is then put through a concrete mixer-like tumbler, and heavy weights are thrown inside to grind the sand finer.

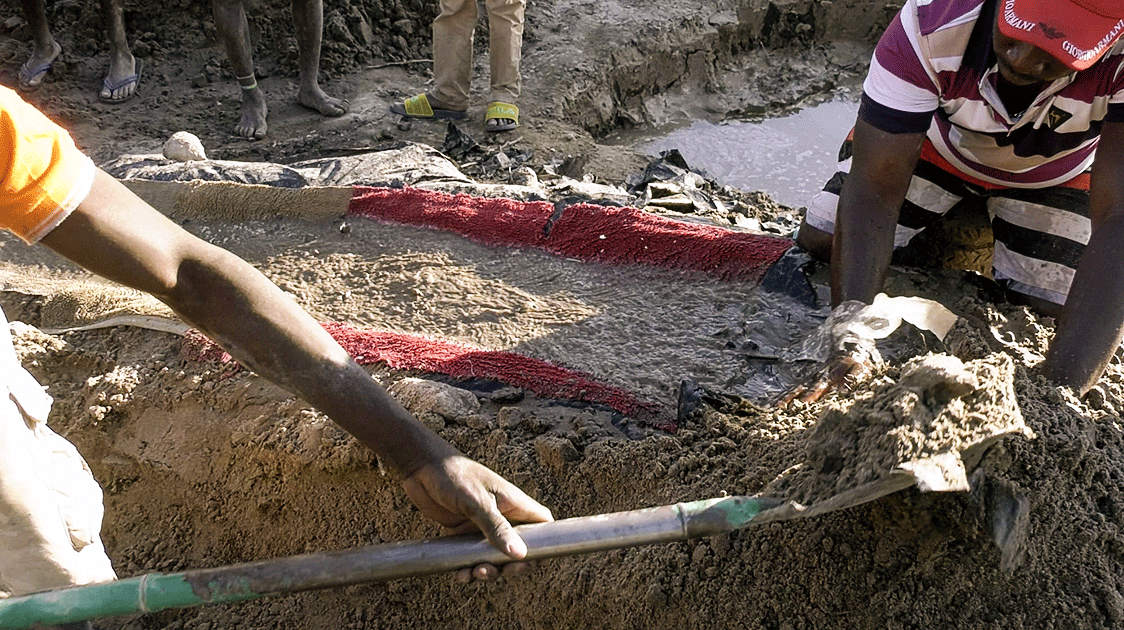

The gravity separation process

The next part of the process is gravity separation. The sand is shoveled onto a sloping channel covered with a ribbed carpet, and flowing water carries away lighter materials while the denser gold particles settle in the carpet's grooves.

The next step is amalgamation. Mercury is mixed by hand with the gold concentrate caught in the carpet. The mercury amalgamates with the fine gold particles to form a malleable mixture.

The amalgam is then squeezed through a cloth, allowing the excess mercury to pass through, leaving behind a solid gold-mercury amalgam. The mercury that passes through the cloth can then be reused.

The amalgam balls are then wrapped tightly in paper, put into a small tin can and placed over a small fire. The mercury vaporizes, and a small nugget of gold emerges.

Although a naturally occurring element, mercury is highly toxic to humans, animals, and the environment. When mercury vaporizes during heating, it poses a significant health risk and can cause neurological damage, kidney problems, and other severe health conditions.

Residual mercury not vaporized during amalgamation and washed into the river system transforms into methylmercury, a highly toxic compound that accumulates in the food chain.

This can persist in the environment for long periods, affecting ecosystems and communities far from the original mining site.

In the past, the mine produced 8-10 grams of gold daily, but the output has dropped dramatically to 1-2 grams. As production falls, the destruction of the river's banks and chemical use rises to compensate for the production loss.

The chief's son oversees the mining operations, and the local government authorities clearly know what's going on. As environmentally destructive as it is, calling it "illegal" is problematic. Who gets to decide?

There's not much else profitable going on around here; the wildlife has been poached out, and slash-and-burn agriculture prevails.

David Gunde has grand and noble plans for a conservancy in Coutada 7, where wildlife and agriculture form the backbone for community upliftment.

But it's an unenviable, mammoth task requiring substantial financial and governmental support.

(Zimbabwean native Zig Mackintosh has been involved in wildlife conservation and filmmaking for 40 years. Sustainable use of natural resources as an essential conservation tool is the fundamental theme in the film productions he is associated with.)

Comments ()