It’s a Human Right, Silly!

By Ian Cox

The environmental right is a human right. Its purpose is to protect us from an environment that harms our health or well-being rather than protecting the planet from us.

The South African Government is obliged to protect this right we have been promised in section 24 of the Constitution to an environment that is not harmful to our health or well-being for our benefit, and for the benefit of future generations, “through reasonable legislative and other measures that prevent pollution and ecological degradation promote conservation and secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development”.

That is a tall order given that many people who hold positions of power and influence in government and amongst opinion makers to whom the government listens strongly believe that we are the environmental threat.

Parliament recognised this when it started laying down the framework for the reasonable legislation that the Constitution requires. Thus, the National Environmental Management Act, 1998 or NEMA, which is the overarching framework law that applies to all environmental law-making in South Africa, lays down clear principles about how environmental law-making and other measures must work.

First and foremost amongst these “environmental principles” is that environmental management must not only place people and their needs at the forefront of its concern but also serve our physical, psychological, developmental, cultural, and social interests equitably.

The second key principle is that development must be environmentally and economically sustainable.

Other fundamental principles include that:

- Environmental management must be integrated, acknowledging that all elements of the environment are linked and interrelated, thus requiring a balanced approach that pursues the best practicable environmental option.

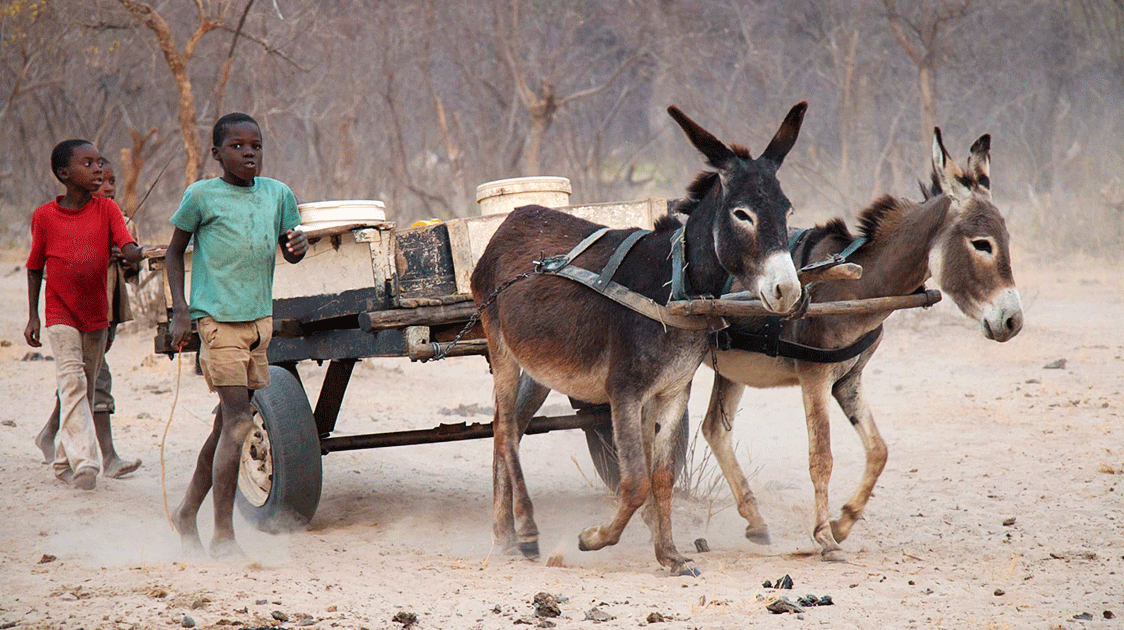

- Environmental justice must be pursued, ensuring that decision-making must not unfairly discriminate against persons, especially the vulnerable and previously disadvantaged.

- Access to environmental resources must be equitably distributed.

- People must participate in environmental governance.

- Decisions must consider the needs of all affected and interested parties.

- Community well-being and empowerment must be promoted.

- Both good and bad social, economic, and environmental impacts must be considered.

- Intergovernmental cooperation and harmonisation must be promoted.

- Global obligations must be discharged in the national interest.

Unfortunately, there is a tendency in government to ignore these principles in favour of what ultimately is a narrow conservationist perspective that sees people as a problem that threatens sustainable environmental management rather than the beneficiary of that management.

You see, very few officials or their advisors understand what environmentally and economically sustainable actually means.

There is a tendency to think that environmental means the same thing as ecological. The result is that environment is often taken to mean the physical world we live in made up in essence of the planet without human beings.

But this is not how our environmental laws define the environment.

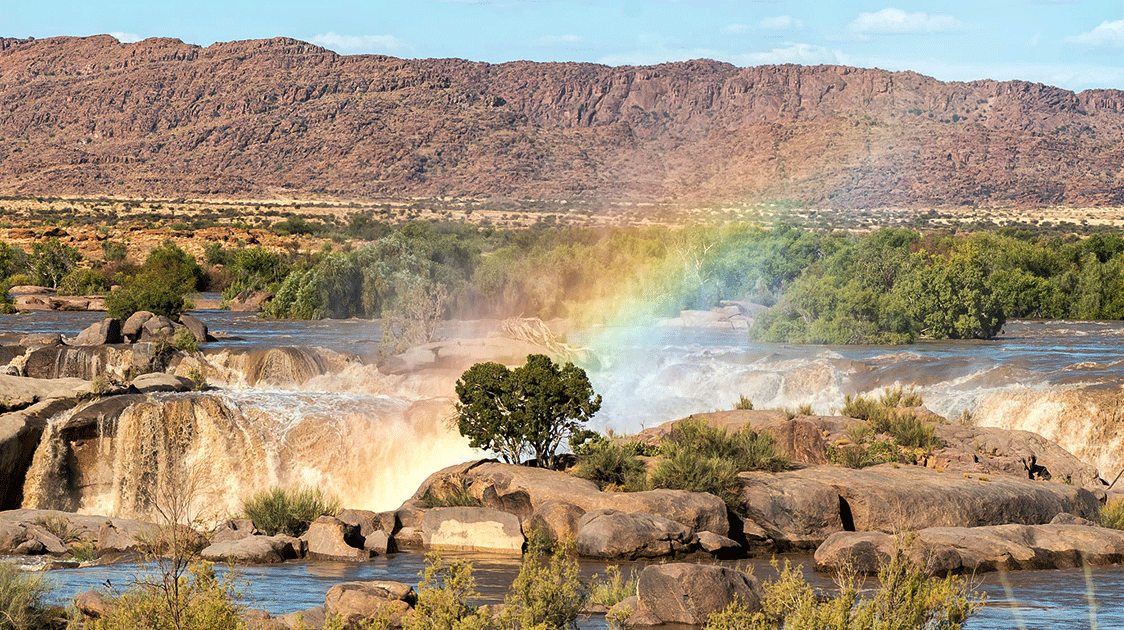

“Environment” is defined in NEMA in terms of the influence the biophysical consisting of “the land, water, and atmosphere of the earth” and “micro-organisms, plant and animal life” have physically, chemically aesthetically, and culturally on our health and wellbeing.

It follows that when we talk of the environment, we do not mean nature; we mean how nature affects us as human beings. When the law speaks of environmental harm, it does not mean ecological harm. It means how threats to ecosystems, species, or habitats do harm or may harm our health and well-being.

I have had this conversation with many senior environmental officials and senior and respected scientists who advise the government.

I can tell you that they do not get it.

Like the muggles in Harry Potter’s world, their eyes slide past the issue and fix on matters they do understand, like man as a polluter, as a destroyer of biodiversity, or a degrader of ecology.

This is hugely problematic because it blinds them to the true nature of environmental rights as human rights. It encourages a perspective that sees sustainable development from a perspective dominated by a conservationist outlook rather than one that balances conservation issues in a broader inquiry that considers socio-economic factors in the transformational context that the Constitution requires.

I believe that this misalignment between environmental practice and constitutional values is the cause of much of what is going wrong in the environmental space these days. One consequence is that present environmental practice increasingly undermines the rule of law and, indeed constitutional rights that underpin human dignity.

Another is that it weakens environmental management systems and thus will make it increasingly difficult for the government to deliver on its environmental mandate.

This is all doing and will continue to do great harm to human health and well-being.

(Ian Cox is an attorney practising in Durban, South Africa. He earns his living as a commercial lawyer but in his free time works to defend and uphold the Constitution in the environmental space. He has also been involved in defending initiatives to allow poor communities greater access to South Africa’s freshwater fishing resources.)