Kenya’s Dirty Little Secret

The insidious propaganda that safari hunting in Kenya was closed because it was decimating the wildlife populations was perpetuated by animal rights activists and NGOs to the point where it was accepted as the truth by the public. But nothing could be further from the reality.

In the early 1970s, elephant poaching across the country exploded, and safari hunters who were on the ground confronted it daily.

The chairman of the East African Hunters Association first reported the problem to the Kenyan Government in 1973, which promptly shut down the legal safari hunting of elephants. The association then commissioned Ian Parker, an ex-warden of Kenya Parks and an expert in the ivory trade, to investigate. Parker named his report "Ebur", the Latin name for ivory.

The report was given to the U.S. Embassy and the British High Commission, both of which wanted nothing to do with it. The British High Commission attempted to discredit Parker by calling him a fanatic and a hunter, which he was not; he was an ex-game warden.

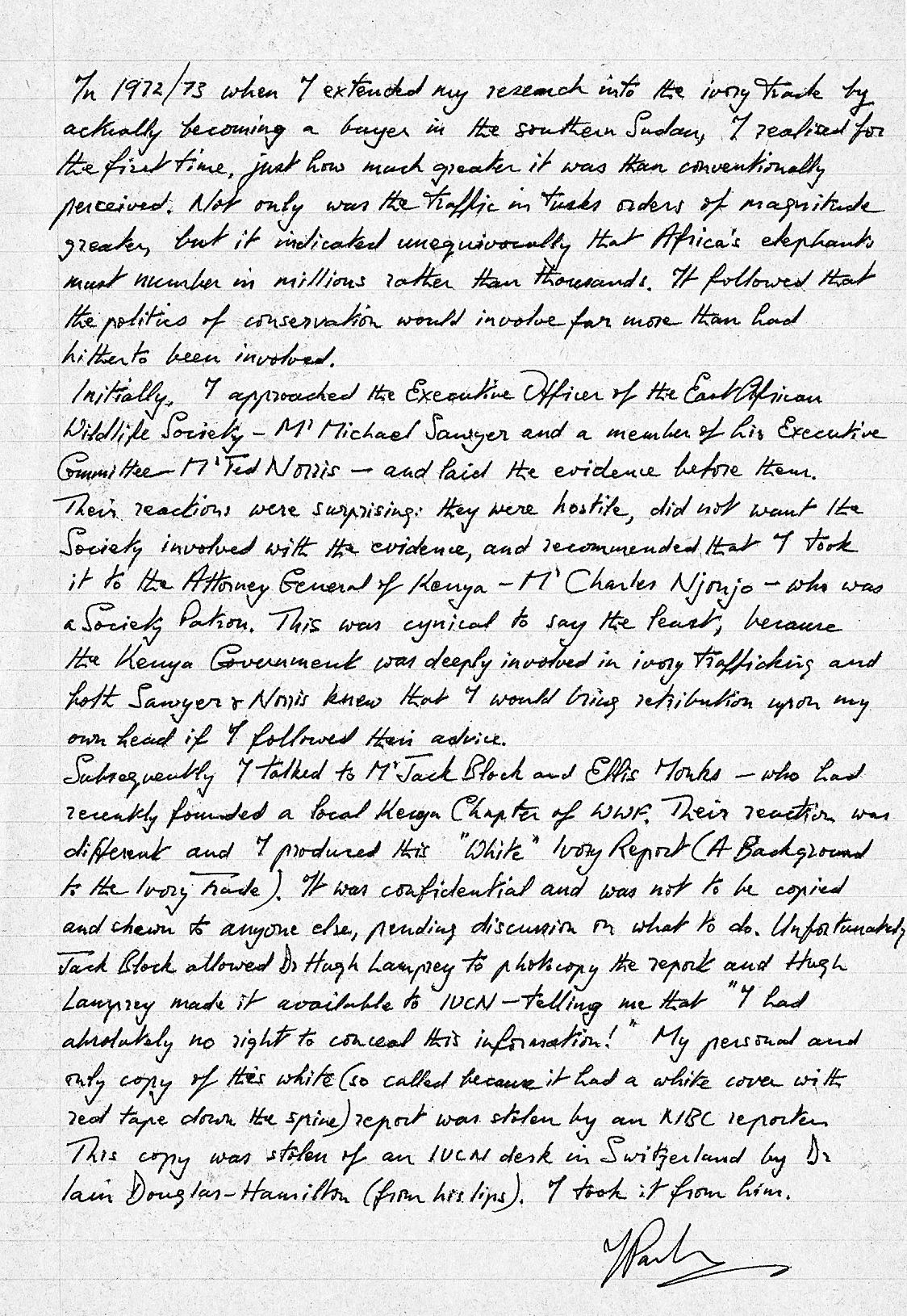

In his hand-written letter (below), Parker reveals that his confidential report was leaked to the IUCN, and an NBC reporter stole his personal copy.

The Kenyan Government abruptly stopped all safari hunting in 1977, and the poaching problem was blamed on professional hunters. Kenya's animal rights NGOs have used this lie to further their objectives and fill their coffers.

A report by the Washington Post at that time reveals the fait accompli.

Below are the contents of a confidential letter written by Ian Parker in February 1975, which lays out exactly how the saga unfolded.

CONFIDENTIAL

In July 1974, I was asked to prepare a report on the East African ivory trade and its political implications. I agreed to do so on a professional basis. The sponsors requested that their names be kept secret.

The report was completed in October 1974. Its salient features were:

1. Current and past policy toward ivory lacked appreciation of its role as a currency, availability and the situation of the majority of people who exploited it. Summarised the position is that irrespective of the needs and lusts of men, if elephants are born, in time they will die.

In dying, they leave freely available ivory. Potentially this is the largest source of tusks in Africa. It is unreal to expect people living in poverty and in proximity to elephant populations not to take advantage of such wealth.

In the circumstances, no law is likely to succeed in preventing its use.

Natural elephant mortality therefore provides an irremovable basis for an ivory trade for as long as elephants exist. Any law-making trade in ivory illegal merely drives the business underground.

This intrinsic aspect of the ivory trade has consistently been ignored. Conservationist argument against free-trading is that while collection of ivory from natural mortality is acceptable or even desirable, it would provide impenetrable cover for illicit elephant hunting.

This is true.

However, an intransigent ban on trading does not remove either the availability or attraction of ivory and if anything, increases the poverty of those who collect it in the first instance.

While the conservationists’ problem is clear, action taken does not seem suitable. More realistic laws are required, and until they are enacted, an illegal ivory trade will exist regardless of Governments and ideologies.

2. On the basis of comparisons between Customs records of East African ivory exports and those of imports by the 'consuming' countries, it is apparent that a substantial illegal trade was taking place long before East African independence.

From the records alone, it is difficult to conceive of this taking place without the connivance and participation of some senior British civil servants. Evidence involving former Game Wardens and Police officers in illicit ivory was presented.

3. Asian influence in the illicit trade was allied to their political fortunes in East Africa. The records suggest clearly that as soon as it became apparent that they were not an acceptable element in independent East Africa, Asians set about exporting capital.

Ivory was a substantial vehicle for such transference. However, in recent times Asian influence appears to have diminished and been replaced by African involvement.

4. Concurrent with the African take-over of ivory trading the volume of ivory exported has risen very sharply - over the 3 years 1971, 1972 and 1973, increases in volume over the preceding year were between 78% and 86% annually.

This is based on the East African records, which are shown to be grossly under-recorded (e.g. in 1973, Kenya's stated exports to Hong Kong were claimed as c. 146 tons, Hong Kong acknowledged imports of well over 200 tons).

Convincing evidence of the minimal monetary losses to East Africa for 1973 indicate that $19 000, 000.00 were banked outside the 3 territories. Of the 3 countries, Kenya was by far the most important in the ivory trade recently.

5. Evidence was presented that many influential Kenyans were involved in ivory dealing. This included the President himself. The Chief Game Warden was obviously pivotal to all recorded ivory exports.

6. It was pointed out that the same level of "corruption" that pertained to ivory also applied very widely in many walks of life in Kenya. In the circumstances, it was considered pointless to single out ivory in the hope that, as a small facet, the 'rackets' might be stopped.

7. It was pointed out that the internal and international potential of the material in the report was considerable and dangerous. It could be used in a variety of ways to rend Kenya's political and social fabric.

In astute hands, the material could be used to embarrass aid-giving Governments before their own electorates if their disregard for obvious corruption in recipient countries could be demonstrated.

The information could badly damage Kenya's future ability to benefit from international charity. Internally, it could be used potently by the current Government's opponents.

8. It was concluded that if the report's sponsors wished to correct the ivory trade, they had no option other than to involve themselves in Kenyan affairs to a degree hitherto uncontemplated. This point was made starkly to get the point over.

However, it was NOT recommended the sponsors should so involve themselves.

Copies of the report were given to the British High Commission and the American Embassy, and they were asked to make comment.

Both returned the report with the statement that it was too "hot”. The report was then debated among the sponsors. Unanimously it was agreed that it should be put to no destructive use. It was felt that if merely divulged to the world public, nothing would be gained except embarrassment.

For all the corruption evident in it, it was accepted that the Kenya Government was maintaining an unparalleled level of civilisation in Africa. If the information in the report could be passed on to those in power in Kenya and thereby stimulate them to consider the consequences of current trends, no better use could be made of it.

The form in which the information should be presented and to whom were never decided. In the interim, someone leaked the existence of the report, its contents, author and the name of one of the sponsors to the Government.

The Director of Intelligence, Special Branch, Kenya Police, made a demand for the report. He claimed direct Presidential instructions to obtain it immediately and guaranteed freedom from prosecution, deportation or any other unpleasantness for sponsors and author.

Great urgency seemed apparent as requests included waking me at midnight. The Presidential demand was debated by the sponsors. The report could bring severe retribution on all having had anything to do with its production. It was felt that it might easily produce a violent reaction from the President, assurances to the contrary notwithstanding.

To offset any such happening, copies of the report were lodged in London with instructions that the information was to be released to the widest possible publicity in the event of any of the people connected with the report being troubled by the Kenyan authorities.

Having taken the foregoing precaution, it was decided to give a copy of the report to President Kenyatta, subject to the condition that it remained confidential and that he would discuss it with the author and the one sponsor known - J. Block.

The reasoning behind this decision was that if received constructively, it could lead to action to reduce the considerable social tensions that are building up in Kenya and which threaten its stability.

If, on the other hand, it was merely shelved, it would reveal a disregard for these tensions that would have considerable bearing on the motivation for current policies in all fields of Kenya's life. Either course would be of value to the sponsors.

During the frequent contacts that preceded and followed the handing over of the report (on 2nd February 1975) to the Director of Intelligence, he was warned that the international Press were aware that something was in the wind.

If they sought the information given in Customs records, they would have much of the basic material contained in the report and would publish it without reference to anyone in Kenya. It was in their own interests to put the report to quick use to avoid destructive criticism.

He made it abundantly clear that the President wished to avoid publicity at all costs and was certain that immediate action would follow his reading the report.

Naturally, I have done my best to locate the leaker who informed the Government that the report existed. Sources inside the Kenya Police Special Branch state categorically that it derived from either the U.S. Embassy or the British High Commission.

The weight of opinion favours the latter, though this admission might well be a fabrication. Several people knew of the preparation of the report, if not its content in detail, and have been spreading its existence around (e.g. John Eames has set at least two journalists from international papers onto asking J. Block and myself for copies).

A further bulletin will be sent you in due course. In the interim, you are asked to file this letter confidentially.

Signed: Ian Parker

15 February 1975

Comments ()