Kruger National Park Management Issues: Water

By Dr. Salomon Joubert

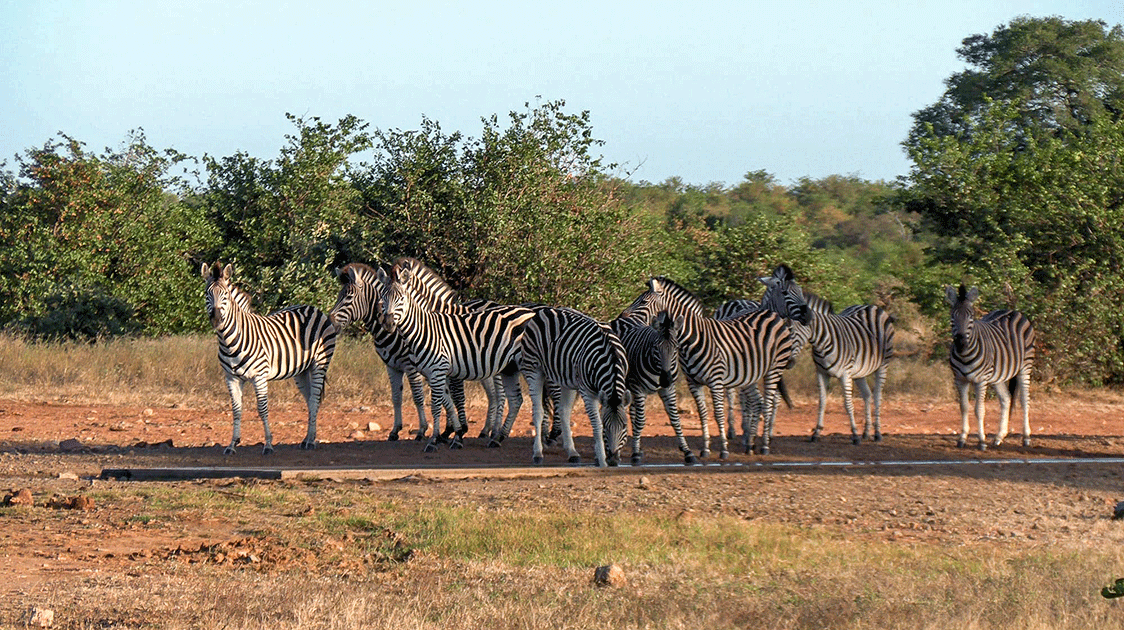

Water provision in the Park has come a long way since the early 1930s. Essentially, the underlying motivation for providing artificial water points was to try and achieve larger numbers of animals (for the sake of tourists) by enticing them to waterless areas with sufficient, under-utilized grazing.

There were also several additional motivations, inter alia, to compensate for the loss of natural resources with the erection of the western boundary fence, to safeguard rare herbivores and endangered aquatic species and to provide resources for periods of drought, especially after the Park was fenced.

The water provision program progressed slowly up to the early 1960s, after which it gained some momentum. However, even at this early stage, it was acknowledged that some dams that were injudiciously placed were defeating their object and causing problems through disruptions to some grazers' spatial and temporal cycles.

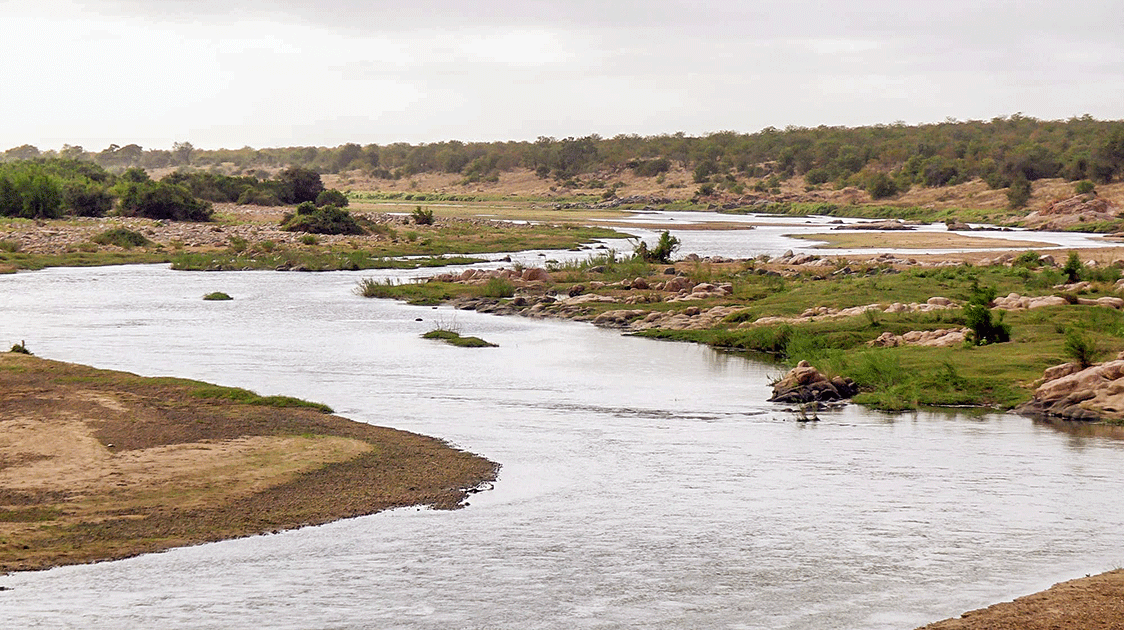

Following several protracted drought years during the 1960s and early 1970s, the water provision program stepped up during the 1970s and early 1980s. This coincided with an exceptionally wet phase of the climatic cycle, which ended in 1982/83—despite the numerous new dams and windmill water points that were provided natural water resources in the form of pans, seasonal watercourses, springs and the perennial rivers provided extensive and superfluous surface water.

Then came the series of drought years from 1983 to 1992, the only period that the artificial water points served any real purpose before the rainfall pattern again improved during the mid-1990s.

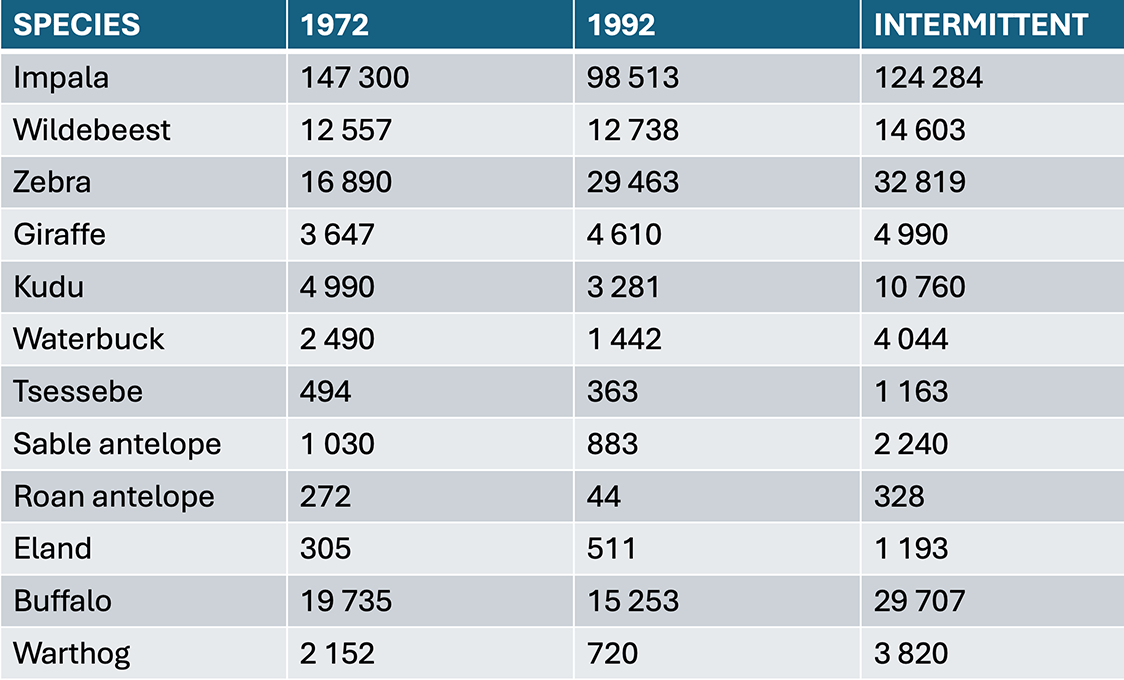

In the accompanying table, the census results for various species are given at the end of the 1960/70's and 1980/90's droughts. These periods were quite similar in duration and intensity, and though the census results were obtained from different methods, the results show a remarkable similarity in the populations at the peak of the droughts – this despite all the water that was provided (zebra and roan are exceptions due to reasons not of relevance here).

I do not think it is unreasonable to conclude that artificial water resources played a minimal if any, role in sustaining the populations through the drought or influencing shifts in distribution patterns.

Much of the new approach towards managing the elephant population is being attributed to the role that the artificial water points have had on the distribution of the elephants.

The question arises: why would elephants be an exception to all the other species?

I agree with the closure of injudiciously placed water points (having personally closed the first 12). Still, I think some of the arguments based on the influence of water on elephants need to be reconsidered.

Table 1: Comparative totals for several herbivore populations at the end of the 1960/70's and 1980/90's low rainfall periods in the Kruger Park and the peaks of the populations in the intermittent (high rainfall) period.

(The late D. Salomon Joubert was the ex-director of the Kruger National Park in South Africa and spent 40 years in the service.)

Comments ()