Landscapes and Appropriate Land Use

In the 1970s, Kenya was a leader in game ranching research, and Kenyan professor David Hopcraft was one of the pioneers. As a teenager, he was fascinated with desertification processes, and finding a solution to this problem became his life's mission.

After completing a master's degree at Cornell University, Hopcraft received a grant from the United States National Science Foundation to study the model of wildlife ranching as a viable means of land use. He started his research on a cattle ranch by putting up fenced enclosures with cattle on the one side and antelope on the other.

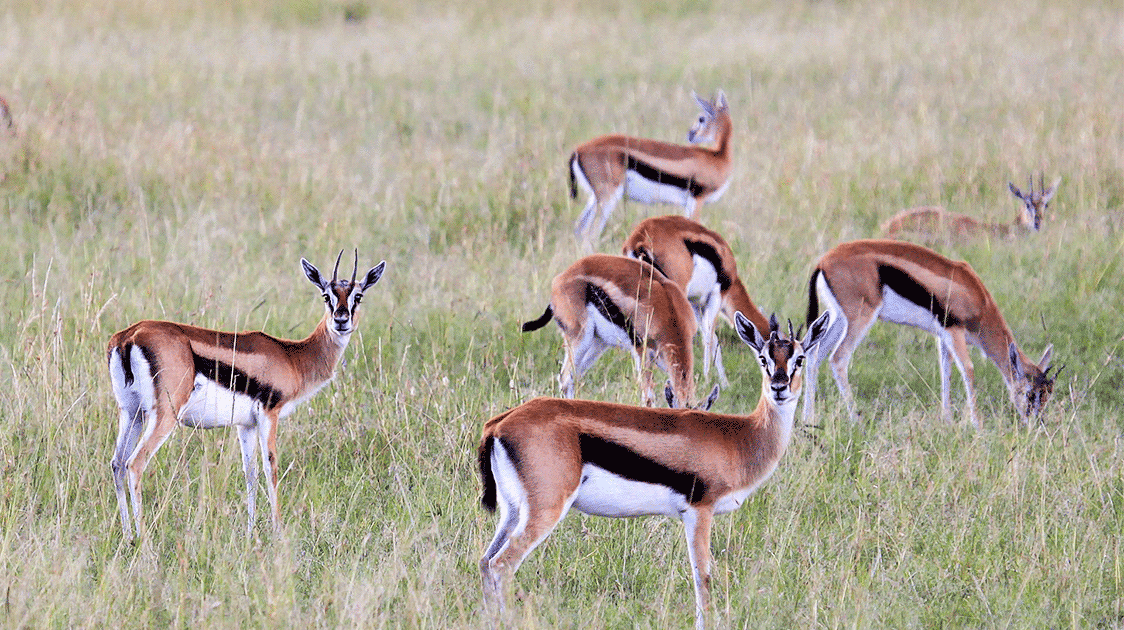

Within a few years, the results proved enlightening. Firstly, the productivity of antelope outstripped that of livestock in lean meat production. Secondly, the antelope enclosure range stayed in good condition.

In the livestock area, the land and vegetation started to degrade and disintegrate through hoof pressure—paths to the water troughs formed lines of erosion.

He found dramatic change by measuring vegetation and cover species diversity. Fewer and fewer species were surviving in the livestock area, whilst the opposite was confirmed in the wildlife area.

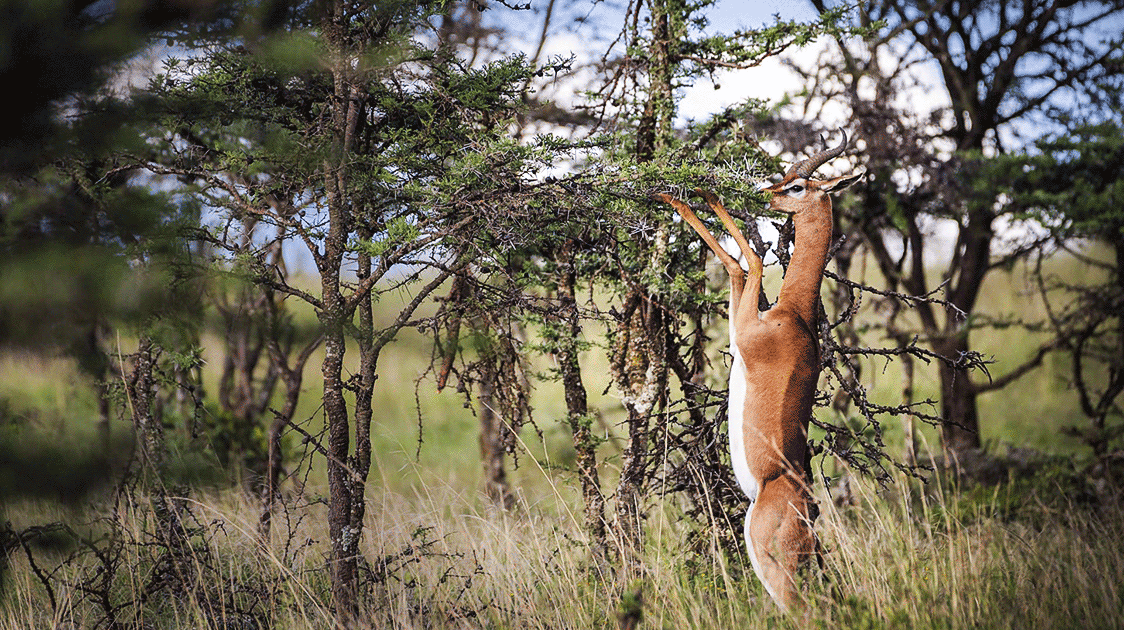

The reason that wildlife did better and did not destroy the habitat centered around water. The antelope species that Hopcraft used in the research did not need to drink water, so he removed the water supply.

This action brought about several environmental benefits. The flattening of the vegetation by the hooves of the animals walking towards the water stopped, and the ground was no longer compacted into a hard pan, so runoff was reduced significantly when the rains came.

The provision of water for either livestock or game animals is expensive. Wells must be drilled, and pumps, fuel for the pumps, tanks, piping, and labor are necessary to run and maintain the systems.

Hopcraft wondered why these wildlife species didn't need water and the mechanisms behind the process. His research showed the animals could eliminate most of the water lost in urine. Urination lasts only a few seconds, whereas a domestic cow can urinate for up to 10 minutes.

Long convoluted tubules in the game animals' kidney system concentrate the waste with minimal water. Most of that water comes from metabolic water, a byproduct of carbohydrate digestion.

The difference in the composition of the droppings was also a critical factor. A cow produces a pat full of water. The nitrogenous waste is converted to methane and ammonia and released into the atmosphere, causing atmospheric issues.

With antelope, the food goes through the large intestine; the waste is converted into little pellets covered in a mucus layer. The mucus layer maintains an anaerobic environment, so all the microorganisms survive using the nitrogenous waste and take that back into the soil.

Another interesting thing he discovered was that a large percentage of the water loss is through panting, evaporation and sweating. Using telemetry, he found that these species acted precisely like cold-blooded animals. When it gets hot, they get hot; when it gets cold, they get cold. They don't keep a constant temperature like humans or cattle, so there is no water loss through sweating or panting.

Adaptation over millions of years has produced wild animals that can not only thrive in the African environment without destroying it but also assist it.

Hopcraft's research showed that game ranching is more environmentally friendly than cattle ranching. Instead of embracing the concept of game ranching and becoming a leader in the field, Kenya adopted an anti-utilization policy, thereby debasing the wildlife resource and accelerating its demise.

The vanishing wildlife through poaching, which cattle replaced, meant that not only were the wild animals disappearing but also all the insects and organisms that lived off the different kinds of droppings.

At the end of the day, conservation is all about landscapes and appropriate land use, not iconic wildlife species.