Pachyderms (and Paradise) Lost

By Hank's Voice

A New York Times article on September 1, 1973, declared, "Kenya has banned all elephant hunting in the country and all dealings in ivory". At the time, J.K. Mutinda, Kenya's chief game warden, said that 99% of elephant carcasses in Kenya's game parks bore evidence of poachers' spears, arrows or snares.

The authorities estimated that about 12,000 elephants were being poached per year. Rumors swirled that many Kenyan residents were buying up ivory and exporting it illegally to get their money out of the country and avoid exchange-control regulations.

The official Kenyan government line was that it recognized that elephant populations were plummeting at alarming rates and that drastic measures were necessary to preserve the species.

It symbolized a shift in policy from utilizing wildlife as a resource to viewing it as something that needed protection for future generations.

With this shift, Kenya assumed "leadership" in African wildlife conservation, making it the darling of Western NGOs and animal rights groups. But not all was as it seemed.

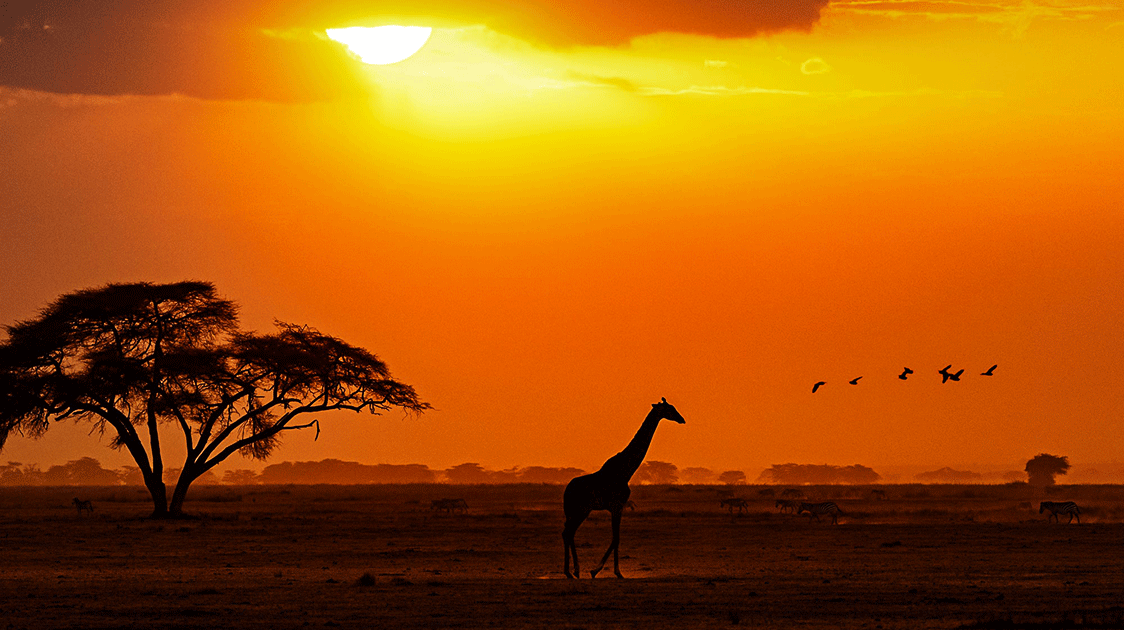

The Tsavo National Park was created in 1948. However, during the 1960s, there was concern over elephants destroying woody vegetation, further aggravated by drought and increasingly frequent fires.

This recognition of an "elephant problem" led to a debate about whether culling should occur.

The Tsavo Research Project was established in 1966, and aerial surveys estimated the park's population at a minimum of 35,000.

Culling was rejected as a solution in favor of simply "letting nature take its course".

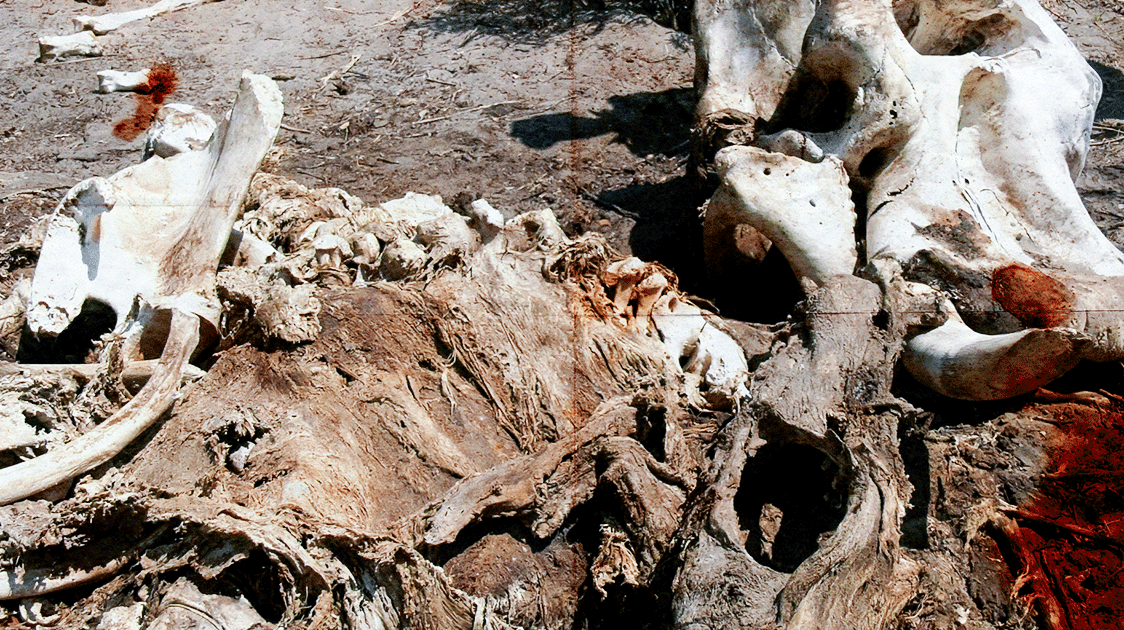

Consequently, around 6,000 elephants died of starvation in the 1970-1972 drought, mainly in Tsavo East.

By 1974, the Tsavo Ecosystem elephant population was declining at an estimated 4% per annum due to numerous causes, including poaching. Ivory prices increased sharply in the 1970s, stimulating an increase in poaching at first, primarily from the poisoned arrows of Indigenous Wakamba hunters.

Before 1975, there were two wildlife authorities in Kenya – the National Parks and the Game Department. The latter was responsible for the Ivory Room in Mombasa, where the country's ivory stockpiles were stored and from where they disappeared.

In 1975, these two departments merged into one - the Wildlife Conservation and Management Department but funding became problematic.

Revenue from legal elephant hunting was no longer available, and other revenue streams generated by the parks, which went directly back into operations, were now sent to the central government treasury.

By 1976, Tsavo National Park was under siege, and the field staff were stretched to their limits. Armed Somalis began poaching in the park, and elephant populations quickly plunged to just 20,000.

In 1977, the head of the anti-poaching unit at nearby Galana Ranch was shot dead by poachers. Elephant poaching had been contained on the ranch up to that point. Still, the newly declared ban on all hunting countrywide prevented management from deriving any benefits from wildlife, and they were forced to abdicate, leaving the elephant at the mercy of Somali bandits and poachers.

By the late 1980s, Kenyan parks lacked serviceable vehicles and fuel, and underpaid rangers were armed with malfunctioning WWI and WW2 rifles. Leadership was lacking, and morale was low.

Key personnel were transferred elsewhere, aircraft were withdrawn from Tsavo East, and severe financial constraints prevailed.

By 1987, the situation had deteriorated further, and elephants were being slaughtered across the country.

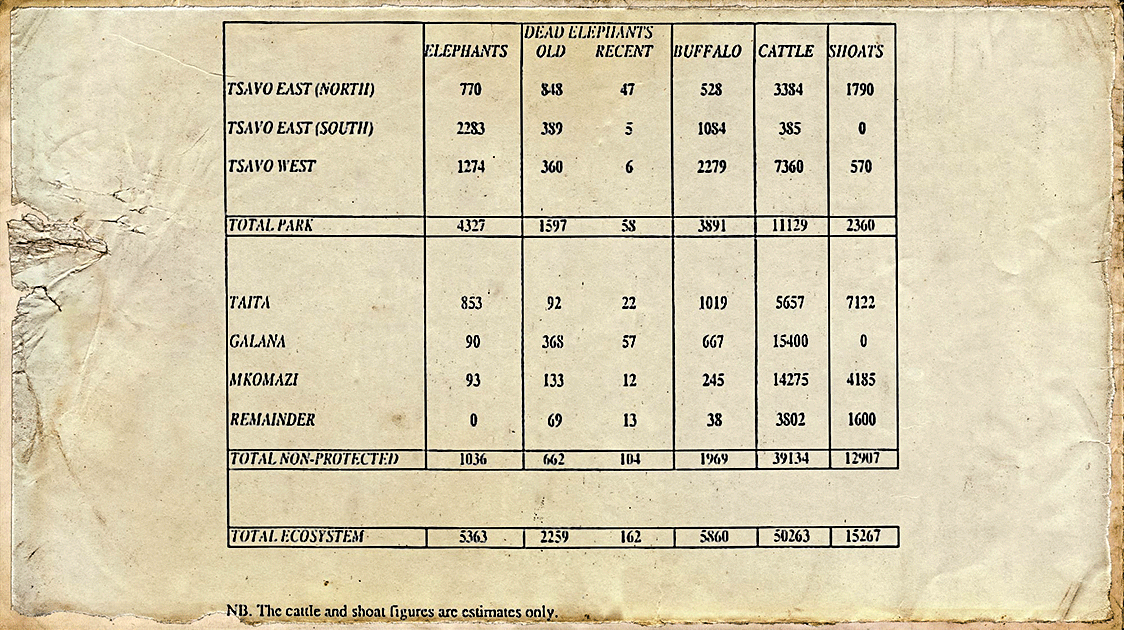

In February 1988, a survey of elephants, buffalo, and livestock was conducted in the Tsavo region, the first of its kind in ten years.

It was funded by an eclectic mix of sources, including the Kenyan Government, European Economic Community, East African Wildlife Society, United Nations, Shell, Firestone, General Motors, Kodak, Ker & Downey, Hilton, Coca-Cola, and various safari lodges.

Eleven airplanes and fifty personnel covered approximately 40,000 km2, including Mkomazi Game Reserve, in neighboring Tanzania.

The count revealed 5,300 elephants, 81% of which were in the Tsavo National Park, a 75% decline from the last major count in 1972.

Tsavo East was almost devoid of elephants. The 6,000 counted in 1972 had fallen to just 770, a 90% decline.

In previous surveys, cattle had never been found in the park. However, in 1988, an estimated minimum of 11,000 cattle and 2,400 sheep and goats were noted, which was likely an underestimation.

Since 1978, livestock have encroached into Tsavo National Park, with illegal cattle grazing increasing since 1982, resulting in overgrazing, trampling of the vegetation and severe erosion.

Tourists were barred from Tsavo East (North), which had degenerated into a free-for-all for poachers and Orma herdsmen with their livestock.

Although seven rhinos were thought to still exist in Tsavo West, none were detected. In the early 70s, an estimated 5,000 lived in this region. The black rhino population was considered one of Africa's most significant.

A total of 3,891 buffalo were counted within the park, with 5,860 estimated in the whole ecosystem—a 49% decline since 1970, possibly due to disease or poaching for meat by local Wakamba settlements.

Vanishing game trails and a noticeable decline of kongoni suggested both subsistence and commercial poaching.

The authorities uncovered corrupt rangers who were colluding with the poachers for a cut of the profits.

They facilitated ivory transportation and did some poaching of their own from vehicles that were provided to help protect the elephant.

In 1988, 27 senior wildlife department officers in Kenya were dismissed for corruption and incompetence. The government also stated it intended to eliminate domestic livestock encroachment into the national parks once and for all.

In 1973, when the elephant hunting ban was enacted, Kenya had an estimated 167,000 elephants.

Fifty-one years later, despite massive anti-poaching, human-elephant conflict mitigation efforts, increased tourism, and other programs, the estimate is 36,000.

In 1969, there were about 42,000 elephants in the Tsavo Ecosystem. This number dipped to a low of 5,300 in 1988, and 36 years later, it has only recovered to around 16,000 elephants.

As livestock numbers countrywide continue to grow, encroachment into the parks endures.

Poaching has not been eliminated, and human-elephant conflict is a serious problem with no end in sight.

In Southern Africa, where safari hunting of elephants is still legal, there is a serious overpopulation of elephants in parts.

So, the question is, did the 1973 elephant hunting ban help save Kenya's elephants?