People Versus Wildlife: The Kariba Dam Saga

By Zig Mackintosh

Progress is perhaps inevitable, but must it come at any cost?

Can a nation of people be expected to embrace wildlife conservation after forced eviction from ancestral lands, where the outside world places a higher value on the life of a wild animal than their own?

The Zambezi is Africa's fourth largest river system, and its basin encompasses some 540,000 square miles. From its source in a soggy marsh in Zambia, the river flows eastwards for 2,200 miles to its delta before finally draining into the Indian Ocean.

The world-famous Victoria Falls is the river's most prominent landmark and defines the boundary of the upper section.

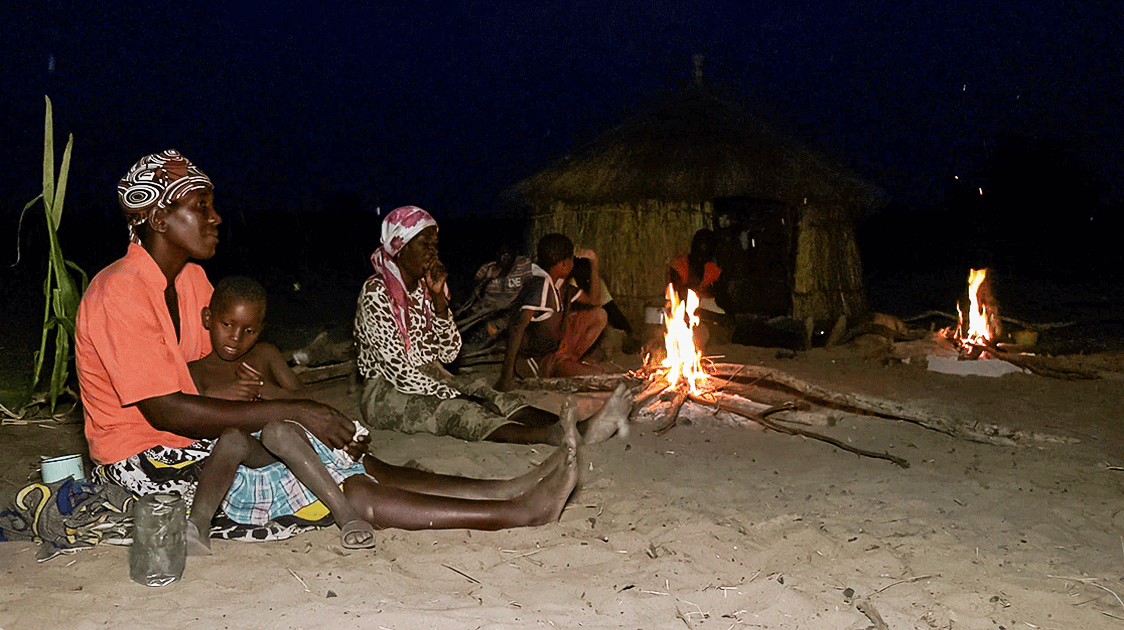

Within the middle Zambezi region lies the ancestral lands of the Tonga people. For centuries, the forbidding escarpments rising from the banks of the Zambezi River, the deadly tsetse fly and the scorching heat isolated the Tonga from the rest of the world.

The river was not just a lifeline but an integral part of the Tonga cultural, spiritual, and social life. They referred to themselves as Basilwizi, "the River People". Villages were located along the banks of the river and around the mouths of tributaries.

The annual flooding of the Zambezi deposited alluvial soils and fertilized their riverine fields. The tsetse fly infestation of the 1830s and the rinderpest epidemic of the 1890s decimated cattle numbers, forcing the Tonga to rely more on goats, sheep, and chickens.

While the Tonga people went about their daily lives, the outside world closed in.

The copper mines of northern Zambia were developing rapidly between 1920 and 1945 due to strong worldwide demand and favorable prices. This, coupled with the brisk growth of the manufacturing sector in Zimbabwe, necessitated a cheap and secure electric power source.

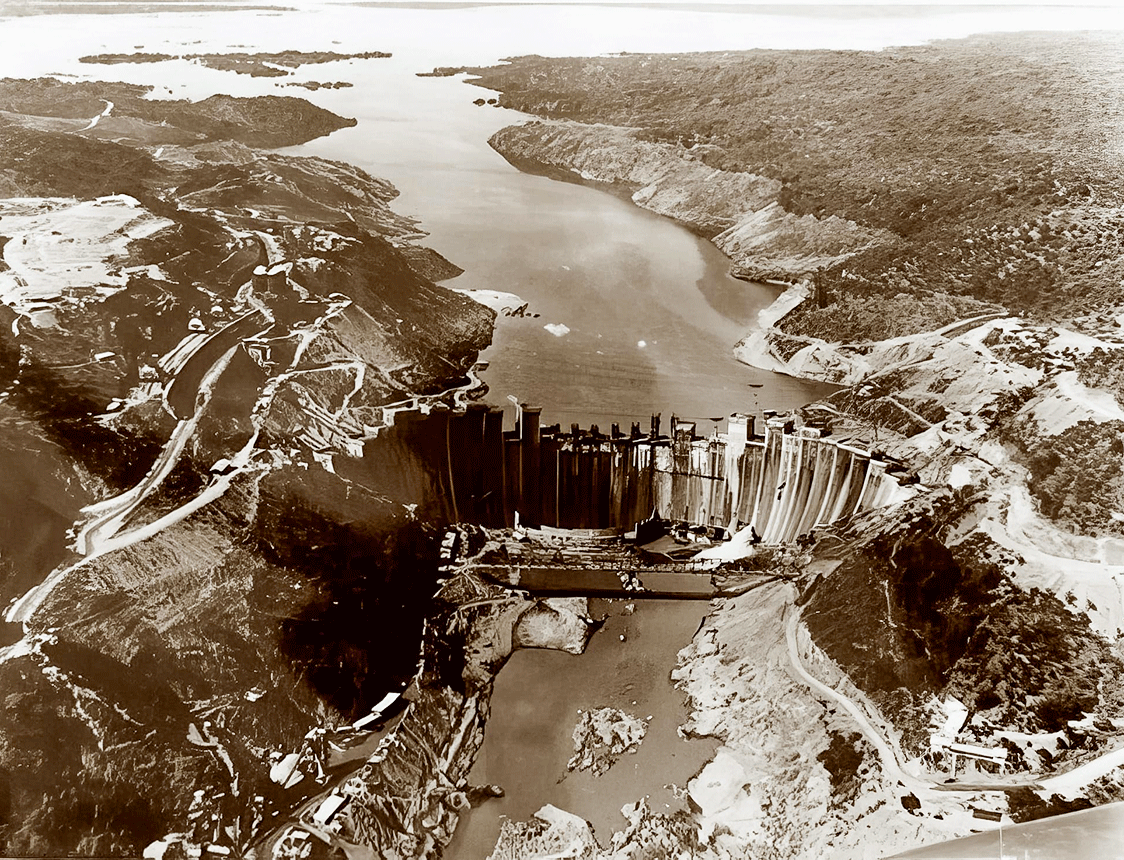

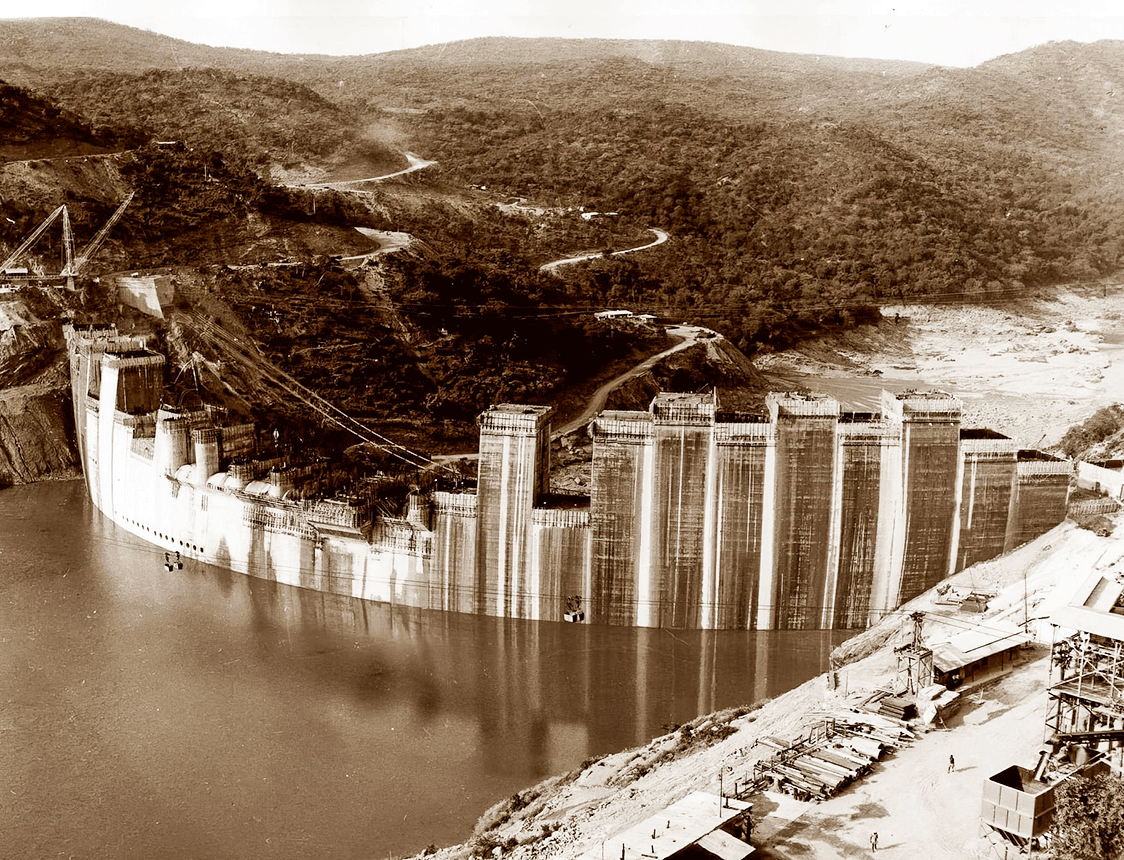

Hydroelectric power was the obvious solution, with the perennial Zambezi River forming the boundary between the two countries. Construction of the dam wall began in 1956, but two floods in 1957 and 1958 hampered its progress.

The Tonga people believed that the floods were the work of their river god, Nyami Nyami, who would never allow the taming of the Zambezi, but in 1959, the dam wall was finally completed.

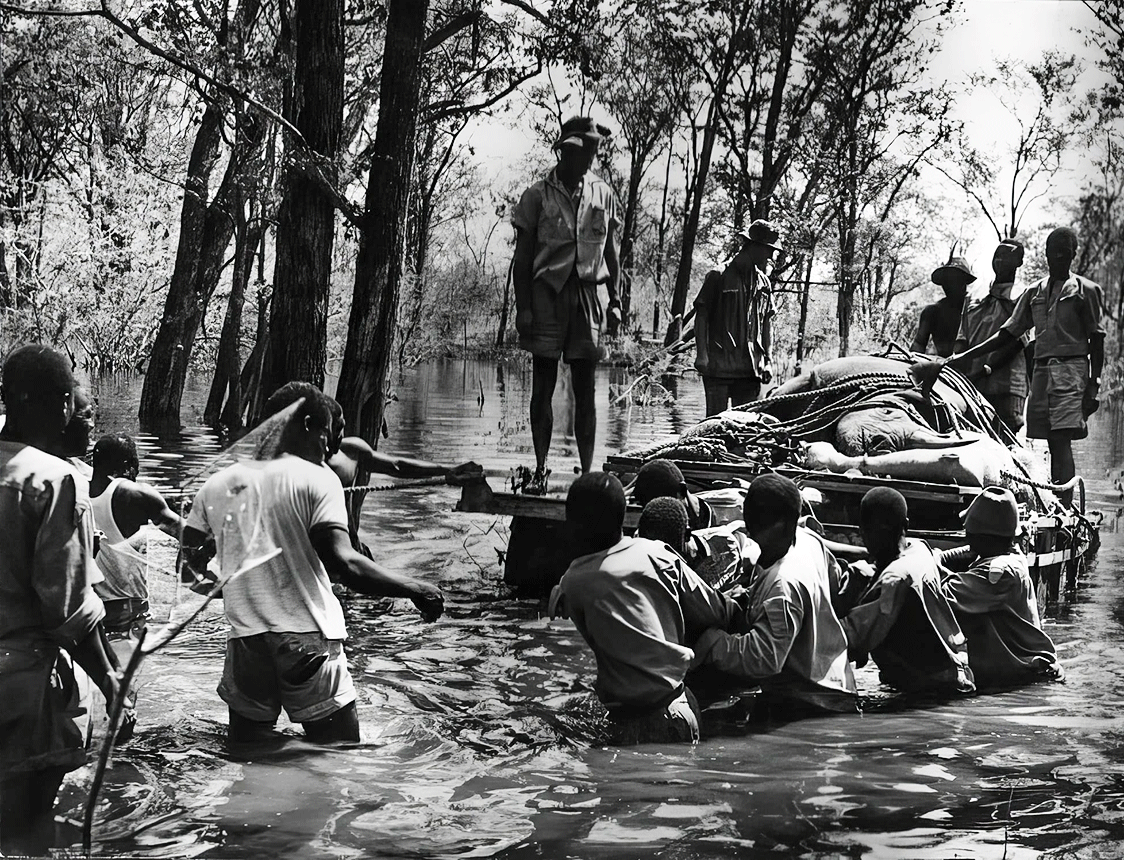

The administration estimated that around 30,000 Tonga people would have to be relocated from the floor of the new dam. The Tonga were incensed about leaving their ancestral lands, and, as if that wasn't enough, the authorities poorly managed the relocation program.

The operation's budget was set at £4 million, but the actual number of people to be resettled had been seriously miscalculated. The numbers were closer to 57 000 than 30 000. Cynically, the budget remained unchanged. This fiasco led to insufficient arable land for resettlement.

The Tonga were unceremoniously bundled into the back of open trucks, forced to carry with them what they could before being offloaded in unknown territory. Their cattle were herded long distances on the hoof, with many dying along the way.

The relocation occurred on both sides of the Zambezi, and the new lake's physical barrier split the Tonga people into two groups.

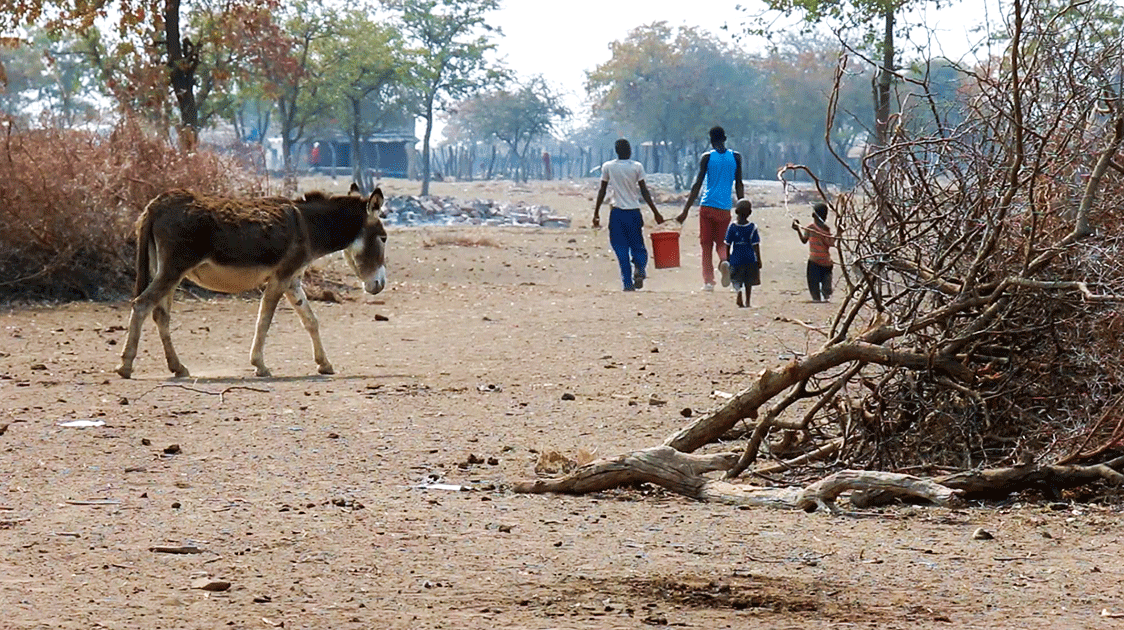

The environment of the resettlement areas was inhospitable. Instead of a fertile floodplain with plentiful water, the Tonga were now faced with hand-tilling poor soils in a highly erratic rainfall area.

While £4 million was set aside for the resettlement of the Tonga people, a much more significant sum was raised from local and international sources concerned with the plight of wild animals in the face of the rising lake. During Operation Noah, 5,274 animals were captured. A net total of 4,129 were saved, nearly 50% of which were the ubiquitous impala.

The authorities also set aside land as national parks for the translocated animals. An evaluation of expenditures between the two operations showed that about £900 was spent per saved animal compared to £70 per person.

While Operation Noah was in progress, the Department of Veterinary Services, Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Control was busy with its own agenda. Their mission was to eliminate the tsetse fly's host, large wild vertebrates upon which the blood-sucking fly depends for food.

The tsetse fly carries the Trypanosoma parasite, which causes sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in domestic animals, particularly cattle. Much of the country was being opened up for cattle ranching, so eliminating the threat of the disease was essential to ensure the enterprise's success.

Between 1933 and 1958, over 148,000 wild animals from 36 different species were shot, including 208 black rhinos. In 1959, the strategy moved away from wildlife annihilation to destroying the tsetse fly habitat and using insecticides and traps.

These contrary administration agendas of forced resettlement, Operation Noah, and the tsetse fly eradication program, combined with the ever-present danger of human-wildlife conflict, hardened the Tonga people's attitude towards wildlife and conservation, which permeated across generations.

This is the crux of the matter; if rural African communities are prohibited from deciding if and how the wildlife resource is utilized, then there is zero incentive for them to protect it.

The international wildlife conservation agencies, both governmental and non-governmental, have it wrong. The ban on the legal trade of wildlife products and the political flip-flopping around the importation of safari-hunted animals are destroying livelihoods and the wildlife and habitat that they profess to be protecting.

Animal activist groups are at the core of the scam. They have no right to dictate to the African people about how to manage their wildlife.

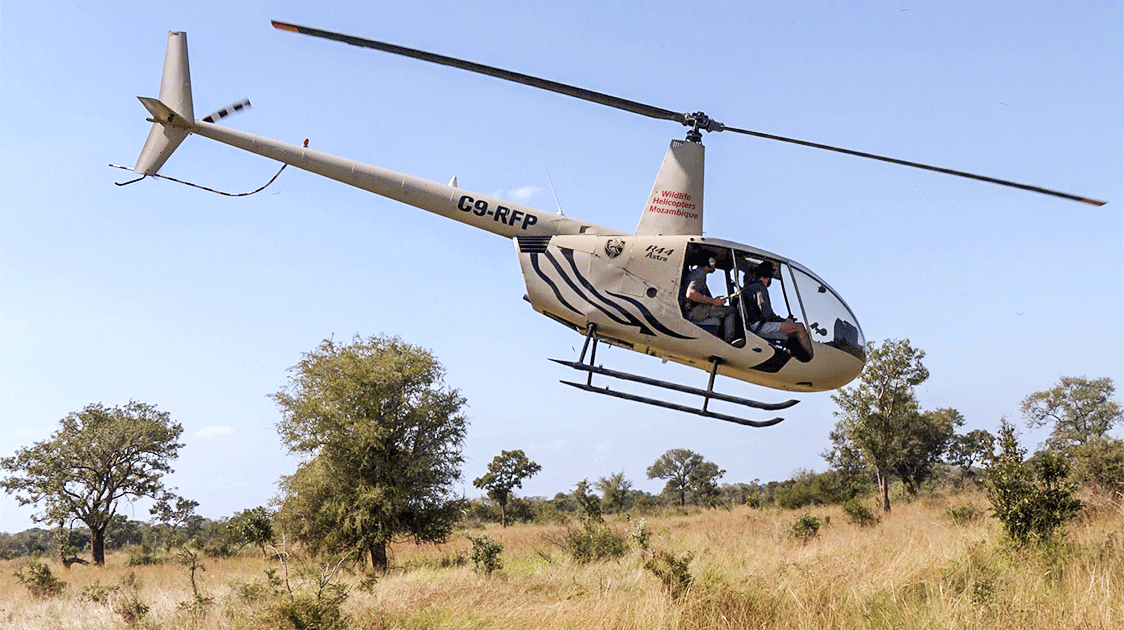

(Zimbabwean native Zig Mackintosh has been involved in wildlife conservation and filmmaking for 40 years. Over the years, he has traveled to more than 30 countries, documenting various aspects of wildlife conservation. Sustainable use of natural resources as an essential conservation tool is the fundamental theme in the film productions he is associated with.)

Comments ()