Should Wildlife be Used as a Food Source?

The Southern African and Kenyan models of wildlife conservation are at opposite ends of the gamut. In Southern Africa, wildlife generally belongs to the landowner and can be sustainably utilized consumptively and non-consumptively if responsibly.

In Kenya, the preservationist model rules: take only photographs and leave only footprints (carbon included!) But there was a time when the Kenyan authorities toyed with the idea of the commercial use of wildlife as a food source.

Ian Parker was a Game Warden with the Kenya Game Department in the 1950s. 1964 he left after eight years and started Wildlife Services, Ltd. with his wife and four friends. Theirs was the first wildlife research and management consultancy in East Africa.

In 1973, Parker submitted a report to the Kenyan Government called "Game Use on Two Kenyan Ranches." The Kekopey ranch at Gilgil and the Suguroi estate in Laikipia were the two ranches.

The idea was to explore the potential for game meat marketing in Kenya and establish cropping techniques within the acceptable hygiene standards applied to domestic livestock. The Kenya Government's Veterinary and Game Departments laid down strict conditions for the operation.

- All carcasses had to be bled out while the heart was still beating. If the animals were shot, only head or upper neck wounds were permitted.

- Body shots resulted in automatic condemnation due to inadequate bleeding and the risk of contamination.

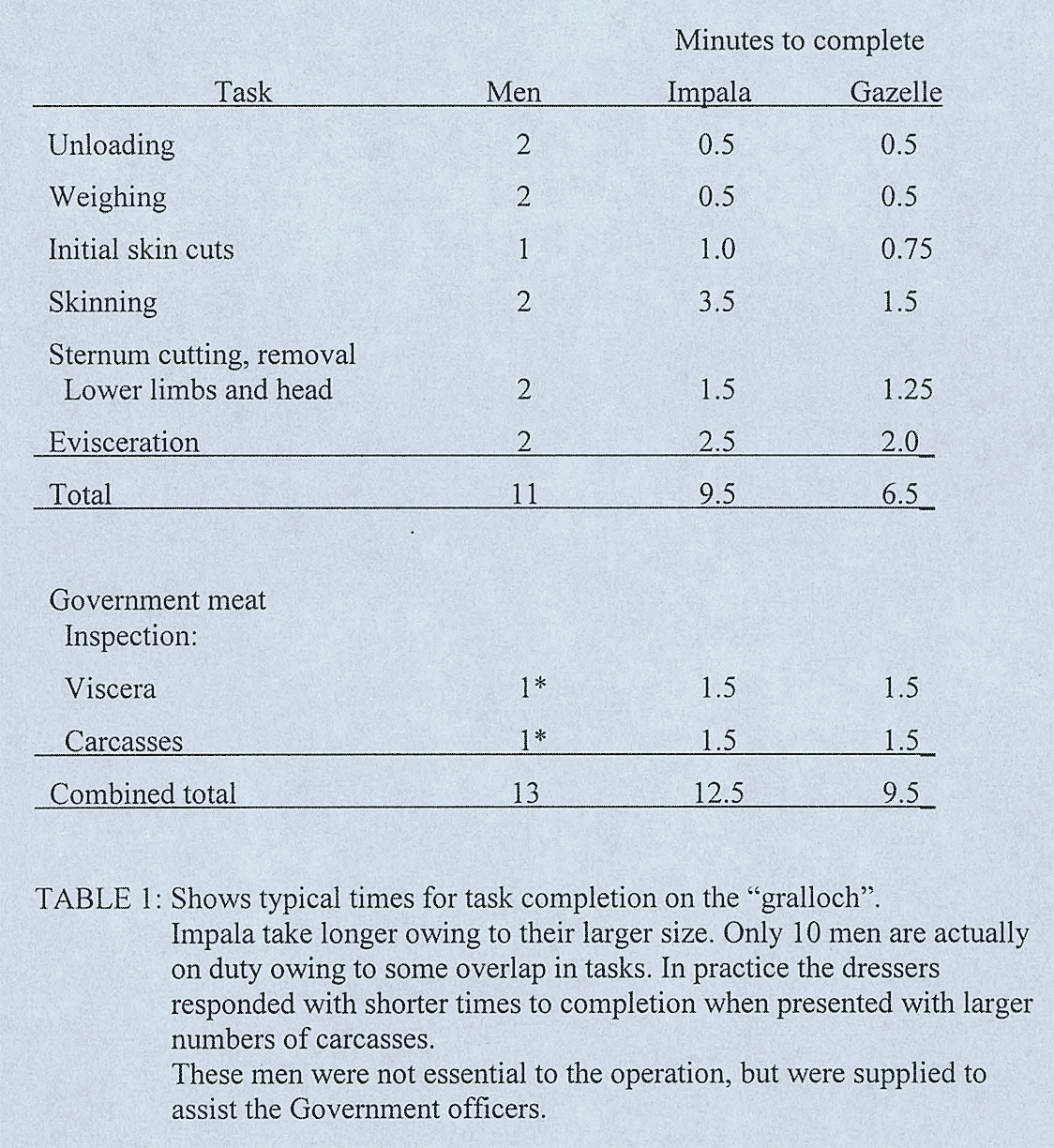

- The evisceration of the animals had to be completed within 60 minutes of slaughter and inspected by a qualified meat inspector of the Veterinary Department.

- Processing of carcasses had to take place in dust and fly-proof conditions.

- All carcasses had to receive the Islamic blessing to make them acceptable to Muslim consumers.

- Carcass bone temperature had to fall below 13° C within 4 hours of slaughter and below 3° C within 16 hours, and the fall had to be continuous with no temporary gains.

The shooting occurred at night during the dark phase of the moon, which allowed close approaches with minimal disturbance to other animals, cooler temperatures, and no flies.

A "Mini Moke" vehicle, chosen for its cheapness and manoeuvrability, carried a driver, shooter, and Islamic meat blesser. Animals were approached within 30 - 70 meters, dazzled with a 100-watt spotlight, and shot through the head or neck.

They were immediately bled out, blessed by the Mohammedan, and loaded into the vehicle. With a daily target of 150 carcasses, hunting and processing continued throughout the night.

Capturing animals in nets was tried to speed up the slaughter rates. A 500-metre nylon net with 250 mm mesh was suspended from a ranch fence, and a herd of gazelle was driven into it.

Four animals were caught, but the carcasses were so badly bruised from the animals' struggles in the net that they were condemned as unfit for sale, and the idea was rejected.

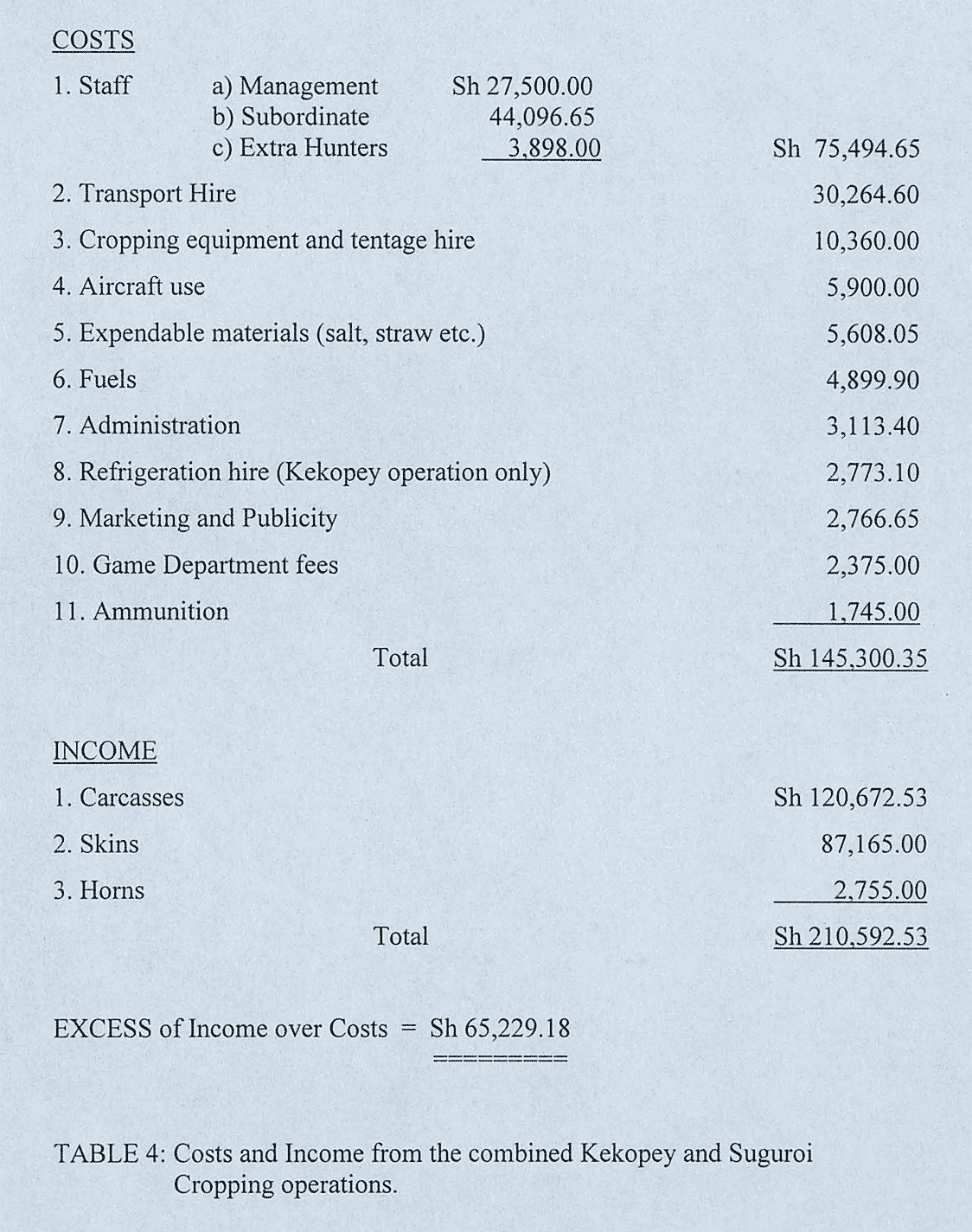

The Game Department stipulated that all carcasses should be sold to or through the Kenya Meat Commission (KMC). The producer sold carcasses at Sh 7.00 per kilo and was charged a handling fee of Sh 0.60 per kilo by the KMC.

The KMC withdrew from the project in December 1971 as it had been unable to sell all the carcasses and ran out of storage. The producers were then permitted to sell directly to meat wholesalers, but KMC still received Sh 0.10 per kilo sold. All skins were sold to Nairobi Hides and Skins Ltd. at Sh 35.00 per gazelle, and Sh 40.00 per impala skin, and the horns were sold to curio dealers in Nairobi.

In his final report, Parker made several observations.

- The experiment was a success in that 2 358 antelope were cropped, and the skins and 35 tons of dressed carcasses were sold with a profit of Sh 65,229.00.

- The marketing of game meat, however, proved to be challenging. Local hotels and restaurants reported little tourist enthusiasm for game meat, contrary to expectations.

- Airlines flying into Kenya showed some interest in serving the product onboard, but no orders were placed.

- Several European buyers were keen, but veterinary regulations precluded the import of fresh meat from tropical Africa into Europe.

- Parker noted that more marketing research would be required before any future investment was warranted. He thought that canning game meat for either human or pet consumption was a possibility, but the demand in Africa was low.

- Only 0.5% of the corned beef production from the KMC was sold in Kenya. The Western market was shaky; public pressure forced a ban on canned horse and donkey meat for pet food. African game meat would undoubtedly be even less popular.

At the time, the demand and price for carcass meal were rising locally and internationally. Parker believed that, as any type of carcass can be converted into meal, there would be no barriers to export if game carcass meal was produced correctly.

The wildlife authorities thought it would be unprofitable, but Parker suspected a more profound psychological reason. "Game", with its connection with "royalty" being too good for a powdered stock food.

Parker's report stated that the trials had established practical cropping techniques but were not easily transferable to new situations or inexperienced operators, as certain aspects required high proficiency standards.

The production of carcasses and skins to acceptable standards set by the Kenya Government was comparably more difficult and expensive than domestic stock. These strict regulations significantly reduced income potential.

Both ranches were capable of cropping operations, just not at the same speed and precision as his company, Wildlife Services. If they had carried out the cropping at their own pace, using only the skins as their source of revenue and disregarding meat production, their income would have been Sh 77,165.00, significantly exceeding the Sh 32,614.59 they received after profit sharing with KMC.

Ongoing cropping operations would only be justified if either the price of meat increased substantially or they undertook the work independently. Parker concluded that it was unlikely to happen as long as the Kenyan Government denied the landowner ownership of his wildlife to develop and manage on his land per his own plans.

He was proved right.

Kenya went down the preservationist road and, since the 1970s, has lost close to 70% of its wildlife through habitat loss and poaching.

In Southern Africa, the authorities have an opposing perspective, and the success of allowing private ownership of wildlife can be quantified.

The State of the Wildlife Economy in Africa Report notes that in 2014, an estimated 21 220 tons of game meat and a further 18 930 tons from biltong hunting across 21 species was produced in South Africa.

Utilizing indigenous herbivores may have lower net carbon emissions than livestock production due to the lower inputs needed in production and lower shipment costs associated with directly supplying local and regional markets.

Game processing had a direct economic value of USD 340 million in 2018. Revenues from game meat have grown at an annual rate of 18% since 2008, and it is estimated that by 2030, South Africa could produce up to 206,000 tons of game meat a year, driven in part by a projected 50% increase in land available for wildlife ranches.

With this irrefutable evidence showing the value of sustainable utilization, it is a mystery why the Western world keeps pandering to the animal rights charade.

Comments ()