Skinny Tracks, Wide Impacts

By Hank's Voice

Western world bicycle paths are paved trails upon which urban dwellers safely enjoy recreationally riding one of the world’s most efficient, affordable means of transportation. But in Tanzania’s hunting blocks, paths created by bicycles are dirt trails upon which poachers from nearby villages travel to steal and illegally transport valuable natural resources, primarily game meat and honey.

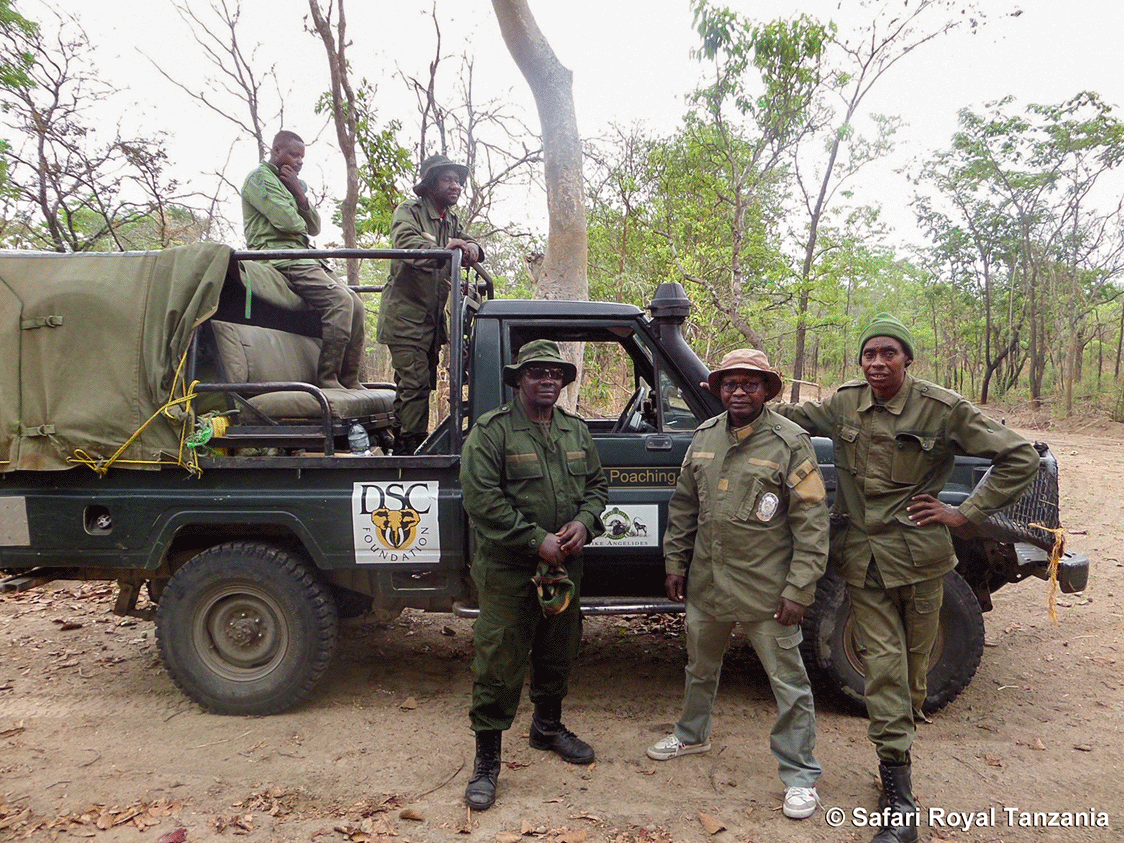

Mike Angelides, the owner of Safari Royal Tanzania, operates in the miombo woodlands of western Tanzania, and his anti-poaching personnel have extensive experience in countering this threat to conservation.

When poachers enter hunting blocks, they cleverly avoid leaving tracks on the roads, as anti-poaching units patrolling by vehicle readily notice the snake-like tracks that their bicycles make in the sandy soil.

Poachers can easily lift a lightweight bike off the road, carry it reasonably far into the bush, and continue riding relatively undetected. One hundred or so meters back into the bush, bicycle paths resume and often fan out, resembling the many branches of a river delta, ultimately leading to spots where meat or honey is poached and collected.

Mike and his staff are increasingly finding that poachers are dragging a tree branch behind their bikes to eliminate deep tire ruts or repeated paths, effectively making their tracks less noticeable. This trend is happening especially in frequently patrolled areas which, with increased patrols, is just about everywhere now.

In any hunting blocks that contain human settlements, bicycle tracks from law-abiding villagers would be difficult to discern from those made by poachers. But in Mike’s wilderness block, the only bicycle tracks belong to poachers, thus necessitating their level of stealth.

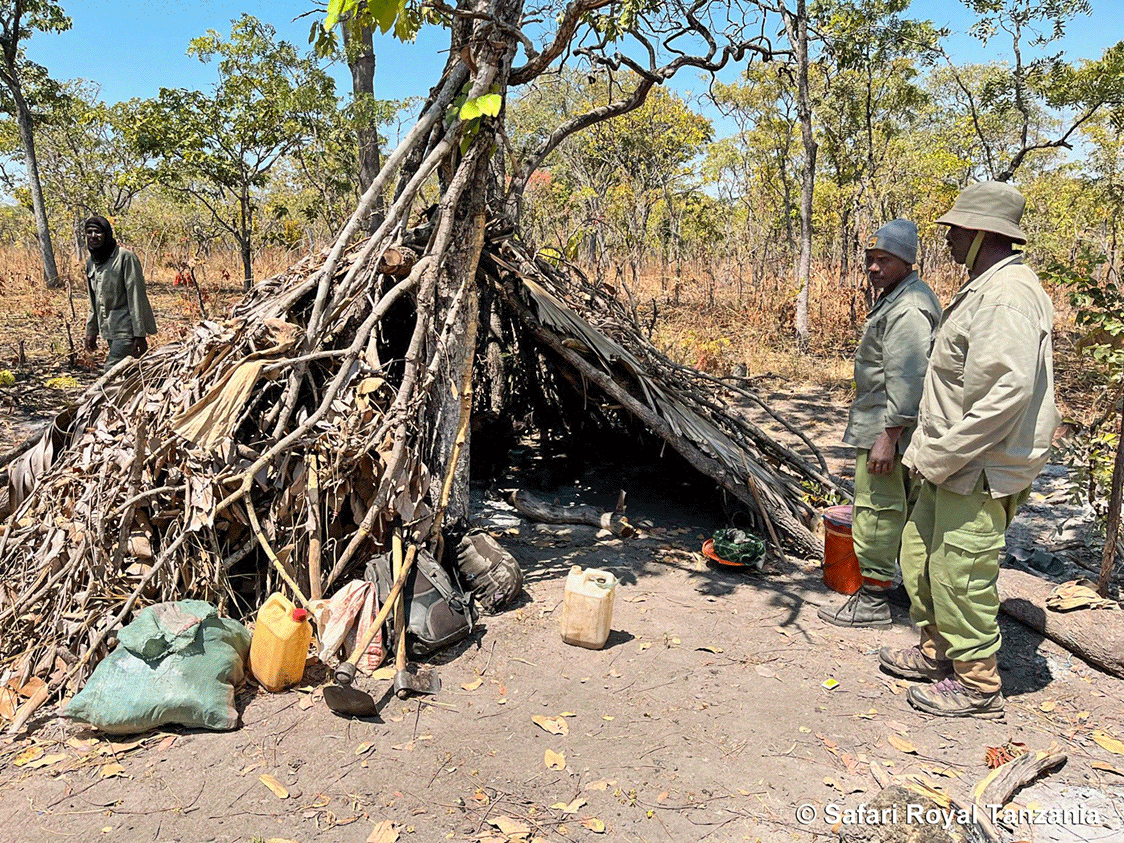

Bicycles are easy to hide in the bush, and poachers are increasingly doing so at their minimalist camps, along with any other gear they don’t want to risk being confiscated.

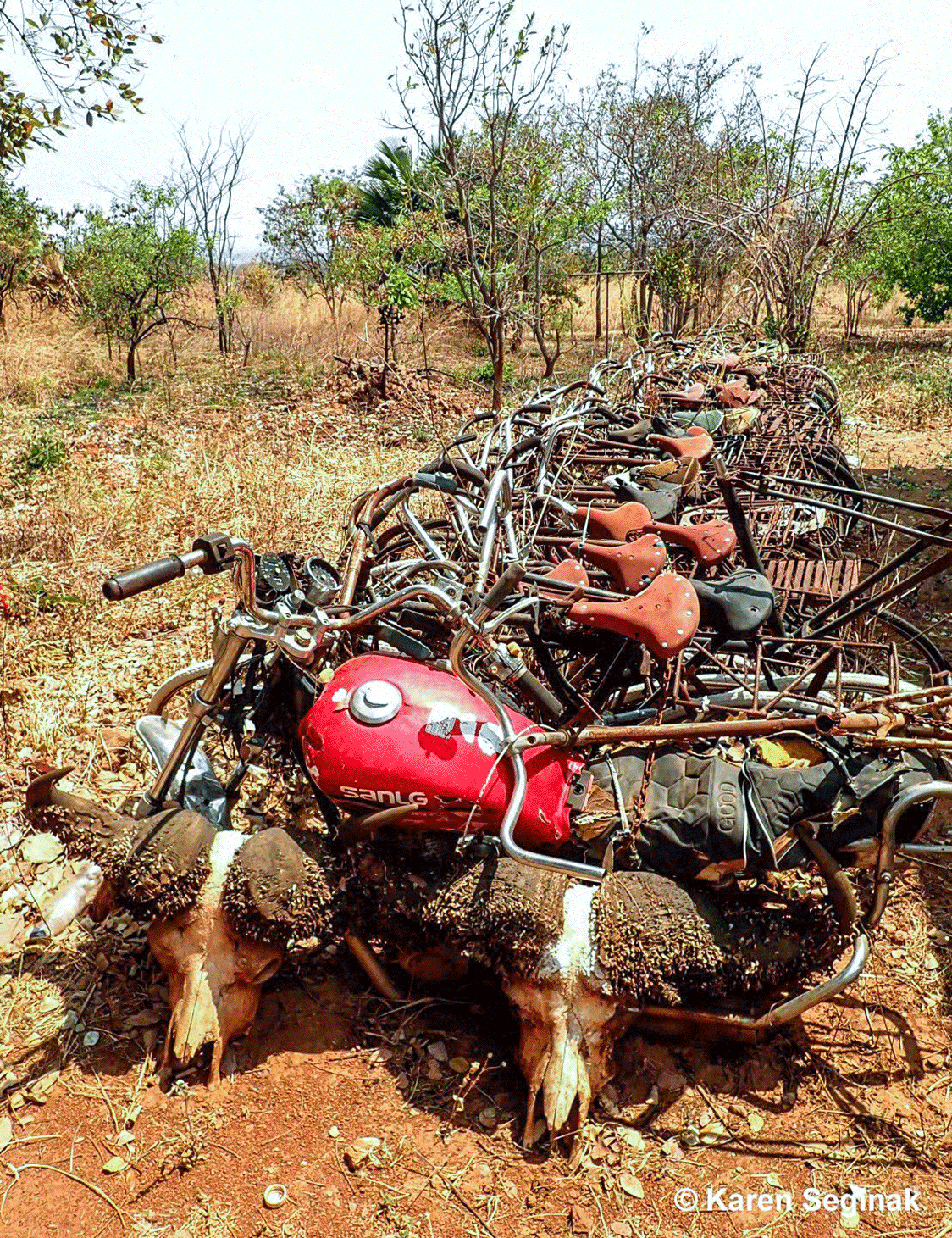

Anti-poaching patrols carry out broad sweeps of 100 to 200 meters around discovered poachers’ campsites to find these hidden items. Confiscating these items may not stop the poachers from striking again, but at least it delays them until they can replace such essentials.

Bicycles also make it easier to transport heavy weights, especially if a pannier has been rigged up on the back, in addition to what the poachers can carry on their backs.

Once the concession boundary has been reached, the bicycles can be easily stashed, and the contraband transferred to the transporters.

Motorbikes are preferred as they are cheaper and less expensive to operate than cars. The poached goods can be whisked away to a distant village far from the watchful eyes of the local game scouts.

Poaching and counter efforts are like co-evolution; anti-poaching operations must become savvier as poachers get wilier.

How do anti-poaching teams become more efficient, and what alternative techniques might be effective was the question asked of Mike Angelides.

For instance, could bicycles be used on patrol?

These hunting blocks are enormous, and it is challenging enough to cover the area even with vehicles, but they could be used on short forays from fly camps.

Game scouts could cover more ground on patrol with electric bikes, but they have limitations, primarily the need for charging after only a few hours of ride time. Solar-powered mobile charging points would have to be strategically located across the hunting concession.

They are also heavy, require training to operate, and are expensive, at around USD 13,000 each.

Motorbikes are an affordable option, but their noise quickly alerts poachers.

They, too, require training and can be highly dangerous off-road for inexperienced riders. Utilizing them for road patrols would save fuel costs, but if left unattended while pursuing poachers on foot could render them vulnerable to theft or sabotage by poachers circling back.

Aerial surveillance is helpful in open country but challenging in the miombo woodlands due to dense tree cover, which also prohibits landing even a helicopter in many places.

A fixed-wing airplane is more cost-effective than a helicopter, but ground patrols must still get a vehicle into the area to apprehend the poachers. This can be very difficult and time-consuming.

The best use of aircraft patrols may be to maintain a noticeable presence to deter poachers and collect GPS coordinates of poachers’ camps.

Appropriately equipped drones are expensive, require experienced operators, have limited range and flight time, and need a reliable power source to keep them charged.

The thick miombo canopy can interfere with the drone’s operating signals, and the engine noise makes them easily detectable. Low-flying drones could be shot out of the air by poachers. Night flights with thermal imaging would help locate poaching camps but would, again, be risky with the forest canopy.

So, the most cost-effective and appropriate anti-poaching techniques are probably the ones currently employed, boots on the ground.

Poachers are tough, can survive on the bare minimum, generally know the topography they operate in and typically have nothing to lose.

The same is not always true of the anti-poaching teams, which require far more logistics. Each team needs drivers, game scouts and two camp attendants to protect the camp while the others are out on patrol, along with a trailer packed with fuel, food, radios, and camping equipment.

The more mobile units available, the more successful the anti-poaching operation; the higher the risk of being caught, the lower the likelihood of willing poachers.

Safari hunting can also help with anti-poaching efforts. While out hunting, the hunting team covers territory for the anti-poaching unit, effectively providing eyes and ears on the ground and acting as a deterrent to poachers.

Although there may be no time to follow up on poaching signs, the information can be relayed to mobile anti-poaching teams.

The hunting outfitter shoulders most of the costs of running anti-poaching operations with help, at times, from their clients and supporters.

When booking a hunt with a prospective operator, safari clients should scrutinize the corporate and conservation responsibility of the outfitter.

Some high-profile operators garner social media attention but invest little in anti-poaching. Just as the skinny, worn-out bicycle tracks of poachers can have wide impacts on ecosystems, so too can thin commitments to anti-poaching.

Helping to expand efforts effectively in situation-appropriate ways, and widening the reach, is the best way to fight the poaching scourge.

Comments ()