Spotty Information: The Chasm Between Delusion and Reality

By Hank's Voice

Jaguars (Panthera onca) are the largest native felids in the Americas and third largest globally, behind tigers and lions. However, they occupy only 51% of their historical range. Although classified as "Near Threatened" on the IUCN Red List, most subpopulations outside the Amazon are "Endangered" or "Critically Endangered" due to small, isolated populations and lack of protection.

Listed under CITES Appendix I since 1975, international trade of jaguar parts is banned. Prior to this, high demand for the European and North American fashion industry for their spectacular skins drove a vigorous but unsustainable commercial activity.

The "jaguar craze" spanned much of the 20th century. In 1968, for example, 23,347 skins were imported into the USA from Brazil alone.

Between 1904 and 1969, an estimated 180,000 jaguars were killed in the Brazilian Amazon, exceeding even the least conservative estimate of the current global jaguar population.

But did drawing a bureaucratic curtain over the trade and banning all legal sport hunting of jaguars stop the killing?

Illegal Trade and Poaching

A 2021 CITES study by Melissa Arias examined the current illegal trade in jaguars. This 141-page document is informative, summarizing information compiled from annual reports, wildlife trade databases, seizure data, literature searches and surveys.

Yet the author cautions that much more research is needed because the study revealed spotty data and inconsistent reporting. The study probably underestimates the actual scale of poaching and illegal trade by orders of magnitude.

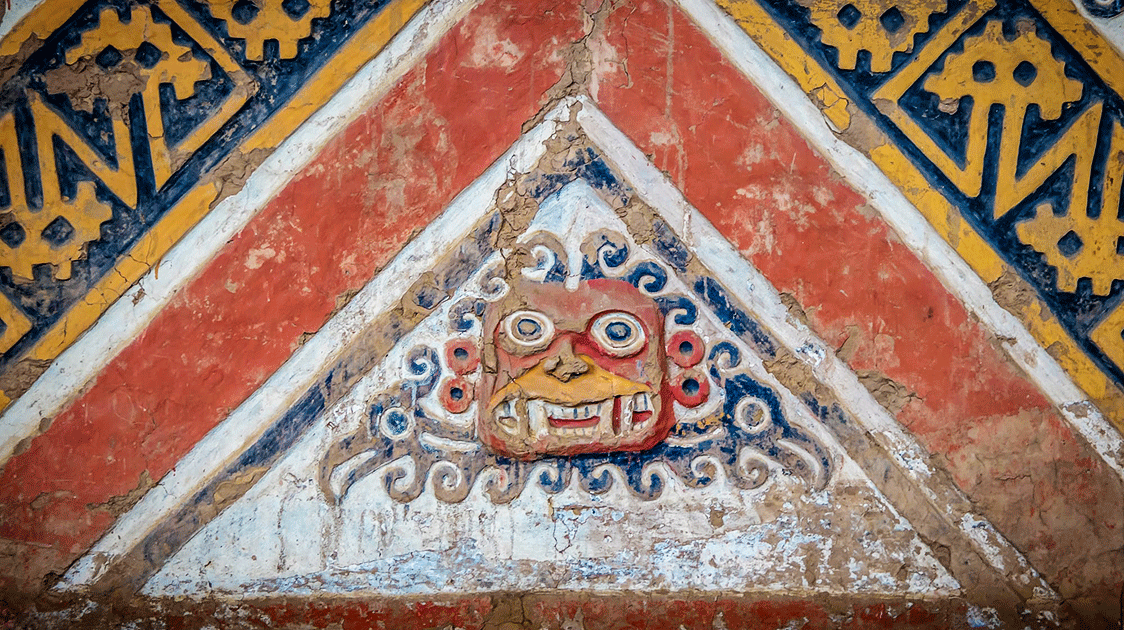

Indigenous and mixed-ethnic groups in Central and South America have long utilized and traded jaguar body parts. This is integral to their culture.

This domestic illegal trade seems to dominate the space but appears to be trending towards more organized international trafficking.

Seizures of jaguar parts (primarily skins and teeth) have remained relatively constant over the past two decades. However, due to differences in vigilance, detection, and reporting in countries or areas, seizure trends are not necessarily the same as in poaching or illegal trade.

To learn more, CITES Notification 055/2020 requested information, with 15 range and 5 non-range states providing inputs.

The number of illegally traded parts reported ranged from 1 in Serbia to 603 in Bolivia. The total number was 689 teeth, 103 live jaguars, 65 skins and 65 unidentified parts.

The numbers reported poached, but not necessarily traded, ranged from one in Mexico to 369 in Panama.

But this data, too, is spotty, as it was from varying time frames.

Between 2000 and 2020, reported poaching across various countries ranged from 206 to 3,955 jaguars annually. Teeth, skins, live animals, and unidentified parts are frequently traded. However, reporting inconsistencies and differences in enforcement obscure the whole picture.

Wild meat hunting is the leading driver of poaching in seven range countries. Surveys in Bolivia found that 40% of respondents had used jaguar parts, while 48% expressed a desire to kill jaguars.

Over half of the 301 poaching incidents in Venezuela from 2001 to 2014 were driven by subsistence hunting encounters.

Forty-two such poaching events from 1995 to 2009 occurred in Argentina's northern Misiones province. Most of these poaching incidents are by wild meat hunters, hunting for other animals, who incidentally have the chance to kill jaguars, too.

Jaguar meat is also consumed. Some cultural taboos suggest it causes sickness, but other cultures eat it for nutritional and/or spiritual reasons. In Costa Rica, the meat is eaten to access the mountain spirits. In Brazilian reaches of the Amazon, jaguar poachers donate meat to local communities.

More than 45 million people in Central and South America hunt and rely in part on wild meat hunting. However, its sustainability is poorly understood, and it can also reduce populations of jaguar prey species, thereby causing more conflict with humans.

Other forest-dependent livelihoods are connected incidentally to poaching, such as collecting Brazil nuts or acai fruit in Bolivia or logging and artisanal gold mining in Suriname and French Guiana.

Human-Jaguar Conflict

Habitat loss and fragmentation due to deforestation for agriculture expansion (soybeans, palm oil, cattle, and subsequent growth of human settlements) heighten human-jaguar conflict.

The economic loss of livestock leads to fear, loathing, retaliation and persecution and the jaguars killed in these conflicts provide contraband for the illegal trade.

In Venezuela, 42% of documented jaguar mortalities from 2001 to 2014 were due to conflicts. In 4 years, 85 cattle ranches in Bolivia killed 347 jaguars.

Belize's estimated annual offtake due to livestock depredation is 200, roughly 45% of the population residing outside the two main protected areas.

Lethal control in conflict is allowed, and no utilization is permitted, but invariably, body parts are extracted.

There have been cases where ranch staff intentionally injure calves to attract jaguars to kill them for rewards from ranch owners. In Panama, ranchers sometimes offset their economic losses by allowing poachers to use jaguar body parts as pay.

Blurred legal lines complicate matters. 14 out of 18 countries (78%) have no specific jaguar laws or regulations, and only half have national jaguar conservation plans.

Cultural and Commercial Uses

Indigenous people and mixed-ethnicity groups can legally hunt jaguars in some areas. Some illegal trophy hunting does occur, with the most organized form thought to be in Brazil, but this is a relatively low threat compared to other forms of poaching.

Jaguar body parts hold cultural and economic value. Teeth are prized as jewelry and status symbols. In Belize, community leaders, government officials, and military personnel are seen openly wearing jaguar teeth. Skins are used for traditional costumes and, especially in Argentina, for horseback riding gear.

Skulls and taxidermy heads are decorative items or trophies in Costa Rica homes. Tail tips become keychains.

Claws and paws can be found at souvenir markets, particularly in Peru. Organs and genitalia are used medicinally in Mexico, Belize, and Bolivia, and fat is used in traditional medicine as well as a repellent for crop-raiding herbivores.

Tourism may be a leading driver of poaching in some countries. In Peru, in one year alone (2018 to 2019), 102 body parts were seized by the authorities at 27 craft markets.

Jaguar parts are openly displayed where tourists gather, and hotel staff and tour guides may be intermediaries in this illegal trade chain.

"Ayahuasca tourism" is a major driver as well. Bracelets and pendants made with jaguar skin and teeth, especially in Peru, are sold to increase the effects of this traditional herbal psychoactive brew.

In Bolivia, illegal trading behaviors amongst local communities are more strongly associated with tourists of European descent than with domestic Bolivians or the Chinese.

Live jaguars, especially cubs found in their dens or after their mother is poached, are also illegally trafficked. Kept as pets or sold to tourist attractions, their possessors are sometimes also associated with drug trafficking and money laundering, as in Honduras, for example.

They are often kept without permits and in deplorable conditions at hotels, restaurants and wildlife facilities in Guatemala, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Mexico.

The sale of jaguar parts and contact details have been boldly featured on Bolivian radio.

Many are traded domestically and exchanged as gifts. Legal businesses are often used as cover-ups to distribute parts. Online platforms, private social media groups, encrypted message apps, and direct approaches to tourists are also selling avenues.

Social media posts and directly approaching communities or through networks of contacts are also utilized throughout range countries.

Advance payment is sometimes made with poaching equipment such as firearms, ammunition, and flashlights.

International Demand and Enforcement

Demand for jaguar parts in the USA is evident, where the most recorded seizures occurred (30 between 2015 and 2019), but this may reflect stricter vigilance.

China, the primary market outside of range countries, has received far more media attention than the USA.

In one case in 2015, a passenger from Bolivia traveling to China via Brazil and France was caught with 119 teeth, 13 claws, and 2 anteater claws. This resulted in a USD 7,836 fine and a prison sentence of four and a half years.

There are no comprehensive studies on the Chinese use of jaguar parts. It doesn't seem to appear in traditional medicine. The teeth are primarily trafficked, and this demand may be related to the Chinese subculture of 'Wenwan' - collectibles that show an owner's taste, discernment and status.

Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama and Peru all signed on to the 2018 London Illegal Wildlife Trade Declaration. Jaguars were recently included in Appendices 1 and 2 of the CITES Convention on Migratory Species.

But are any of these actions solving the problems jaguar populations face?

Conservation Challenges and Solutions

Increased land conversion, resource extraction, agriculture, ranching, and tourism all occur amidst the ever-persistent background of traditional domestic uses.

Yet solutions to enforce laws are limited by finances and human resources. The danger of organized criminal networks, lack of legal clarity, corruption, remoteness, and poor civic engagement in conservation likely prevail, even inside protected areas that are all too often underfunded and understaffed.

Basic logistics like lack of vehicles and fuel hinder efforts, and environmental and park guards are increasingly busy with other violations such as illegal gold panning in French Guiana.

Basic essential information is also lacking. Between 1990 and 2014, less than 10% of peer-reviewed published literature addressed the illegal trade of Latin American wildlife.

Information on legal actions taken is missing, too. Mainstream and social media focus in biased manners on only select (and perhaps minor) parts of the problems, like illegal trophy hunting or Chinese involvement, as domestic trade driven by incidental encounters and conflict is likely far more impactful.

Nine of 18 countries have no literature regarding national population estimates. The two main range-wide population estimates that do exist vary greatly. In 2017, a figure of 64,000 jaguars was calculated, of which 89 % are in the Amazon subpopulation.

A different study estimated 173,000 in 2018. However, these estimates were based on limited robust surveys in protected areas or well-conserved habitats.

Disturbed lands, instead, make up a significant portion of the currently occupied jaguar range. Therefore, present levels of domestic-driven poaching combined with habitat loss and fragmentation may already be problematic for some jaguar populations.

Is it perhaps time to reinstate well-regulated trophy hunting of jaguars?

Could the legal killing of a few individuals each year help to reduce the illegal killing of many more by providing essential funds for habitat protection, population monitoring and anti-poaching?

Will giving a tangible value to the animal create more incentive to conserve the species?

Is it time to try a sustainable-use model?

The current model, quite evidently, is not working.