Standing Too Close to the Elephant – The Amboseli Smoke and Mirrors Show

By Hank's Voice

The video Tuskers: Saving the Last Gentle Giants, produced by the animal rights organization Humane Society International (HSI), seeks to convince viewers that Amboseli's super tuskers are on the brink of extinction—unless trophy hunting in Tanzania is banned. But is that really the primary issue? And does the video accurately portray the Amboseli ecosystem?

Joyce Poole, a star in the film, ironically noted in an Elephant Voices social media post in 2024: "The world is so contradictory." Indeed, this film exemplifies that contradiction.

Do Super Tuskers Drive Amboseli Tourism?

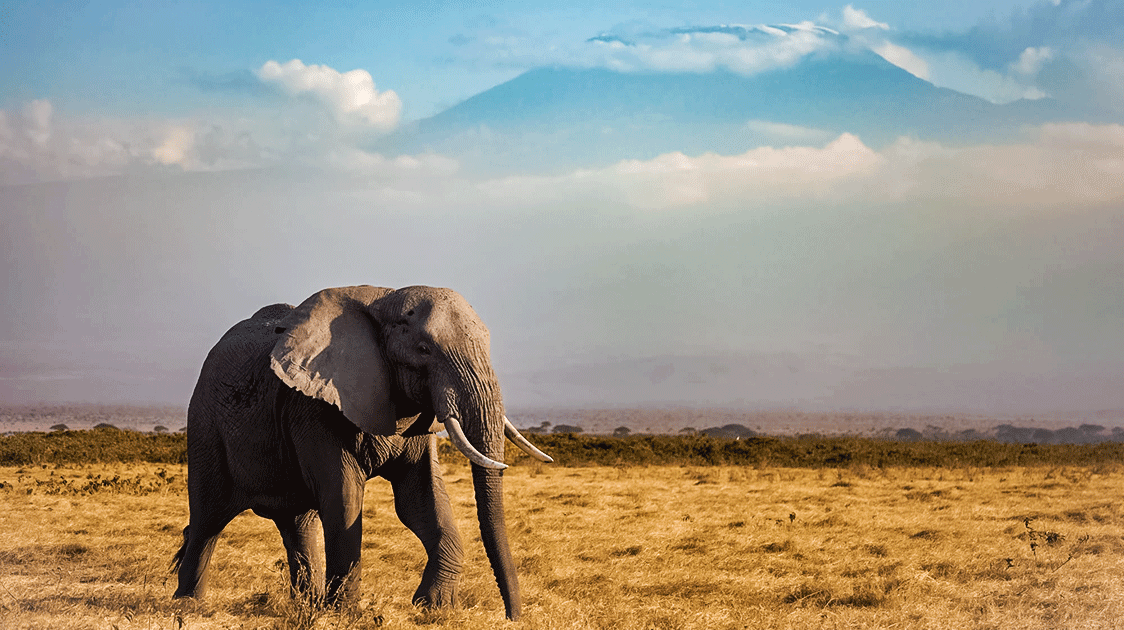

Are super tuskers the main attraction for Amboseli tourists, or do visitors find equal excitement in seeing elephants of any size, with the real highlight being Mount Kilimanjaro rising dramatically from the plains?

While spotting a super tusker inside the park is possible, it's not likely. Take the legendary bull Craig—he primarily roams community lands where off-road driving is permitted, making it easier for photographers to follow him. Within the park, his aversion to the relentless fleets of vehicles makes him elusive, and social media posts frequently urge people to respect his space.

Even Amboseli researchers go months or years without seeing specific bulls. Once males reach sexual maturity, they often remain outside the park, returning only briefly during musth (a reproductive state).

Misinformation in the Film

In the documentary, a camp manager in Tanzania's Enduimet Wildlife Management Area (WMA) claims to promote photographic tourism of big tuskers. Yet, his website contains no such marketing. He also states that guides are "heartbroken" when an old bull is seen alive on a morning game drive, only to be killed by hunters by afternoon.

But which bulls is he referring to?

Most famous Amboseli males are accounted for—except possibly Gilgil. In the same film, Richard Bonham admits he hasn't seen any photos of tusks or jawbones from recently hunted elephants. If that's the case, how does he determine whether these were super tuskers—or even their age?

Moreover, Craig is reportedly monitored 24/7 by Maasai guards and no longer travels far. If true, how could he be vulnerable to hunters in Tanzania?

How Many Super Tuskers Remain?

The film claims fewer than ten remain in the Amboseli ecosystem, and only 50 exist across Africa. However, these figures are widely debated:

- Tsavo East, part of the broader Amboseli ecosystem, once thought its super tuskers were gone. Yet, in the early 2010s, intensive aerial and ground patrols discovered 14.

- Their monitoring suggests 30 younger bulls could reach super tusker status in the next decade.

- On World Elephant Day (August 12, 2023), Joyce Poole stated that only 30 remain in all of Africa. Yet, others estimate over 100.

The truth is many African elephant populations:

- Have not been thoroughly surveyed,

- Exist in denser habitats where visibility is low,

- Are significantly larger in number,

- And/or are still recovering from past poaching crises.

Conflict between bulls is more intense in Botswana, Zimbabwe, and South Africa, where elephants are chronically overpopulated. Many have broken or missing tusks due to fighting. Could some of these elephants have been potential super tuskers?

A Misleading Conservation Narrative

Richard Bonham claims that Amboseli's super tuskers exist because Kenya has protected them for decades. However, since these elephants are transboundary, Tanzania has also protected them. The claim that only Kenya's efforts have safeguarded them ignores the broader conservation efforts at play.

Can Future Super-Tuskers Descend Only from Present Ones?

A 2024 Elephant Voices post stated:

"Although the genetics of tusk shape and size is still largely a mystery, we know that males and females inherit characteristics of their mother's tusk shape and size. We know less about the inheritance of their father's tusks, as we don't often know paternity. But where we do, we have seen some striking resemblances."

The largest tusks ever recorded belonged to an elephant killed on the northern slopes of Kilimanjaro in the late 1800s. Each tusk weighed over 200 lbs. Amboseli researchers believe his genes were passed down through generations.

If this is true, how can the legal hunting of five bulls significantly deplete the gene pool, as some alarmists claim?

A study conducted in Amboseli from 1972 to 2000 could only assign paternity to 119 calves out of 1,238 born (about 10%). Yet, researchers argue that few individuals make an outsized genetic contribution. How can they be sure of this?

For example, when the famous elephant Tim died, researchers stated:

"Without DNA analysis, we're not sure how many offspring he has, but it must be a significant number. His legacy will live on."

This is sheer speculation rather than scientific certainty.

How Many Mature Bulls Are Needed?

Only 3.8% of all males in Amboseli are over 35 years old, and this is supposedly one of the best-protected elephant populations in the world. So how many mature bulls are needed, as the Amboseli population, in general, is considered stable to increasing?

Researchers state that elephants can live up to 70 years but also report that the average male life expectancy from natural causes is 42 years. In the first 47 years of study, only 14 males lived beyond 50.

For example, Paolo, a well-known elephant, died naturally on February 4, 2024, at 46. This was described as a respectable lifespan for a wild bull. If a legal hunter in Tanzania had shot him, critics would, instead, claim he was "cut down in his prime."

Despite his death, no concerns were raised about:

- Disrupting elephant social systems

- Depleting the gene pool

- Devastating Kenya's photo tourism industry

- Crippling long-term research projects

This apparently only magically happens when bull elephants are legally shot.

Are We Really Removing Elephants from the Future?

In the video, Dereck Joubert states:

"We are basically doing a time splice. We are taking them out of the present and removing them from the future as well."

However, most super-tuskers are already approaching the end of their lifespan, meaning they will soon be gone regardless. And Amboseli researchers claim that when old, famous bulls die, their legacies live on in all the offspring they've sired, so where’s the problem?

Should Super Tuskers Be Heavily Protected?

Protecting super tuskers raises questions about natural selection. Researcher Cynthia Moss argued in 2016:

"By killing older males for their tusks, the very individuals who should be breeding are taken out of the population and younger, in a sense – unproven, bulls are mating instead. Eventually, the health and vigor of a population decreases when natural selection is removed and replaced with human selection for males with the biggest tusks".

If excessive human intervention—such as veterinary care and rescues—keeps super tuskers alive, isn't that also interfering with natural selection?

Many iconic elephants have been repeatedly treated for injuries from spears, poisoned arrows, and fights. Some have even been rescued from mud.

Excessive darting has suppressed musth in certain bulls for years. Between 2000 and 2024, the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) treated 3,600 elephants.

Tolstoy, a famous super tusker who died from spear wound infection, had his tusks trimmed because they were too long, and he couldn’t walk properly.

Are Amboseli Elephants Fully Habituated to Humans?

Not all Amboseli elephants are accustomed to humans. Many simply travel through the area, encountering vehicles along their routes. Over 50 years of research have shown that some elephants tolerate people while others remain aggressive.

For example, one bull named Bad Bull would charge at researchers from 400 meters away. On average, 80% of males are only seen eight times a year, making complete habituation unlikely. In the past, researchers even used vehicles to chase aggressive elephants away.

Habituation also depends on location. In the park, elephants have been known to raid campsites, open car doors, and scavenge at garbage dumps, raising concerns about their comfort around humans.

Has Amboseli's Elephant Population Been Free from Hunting?

Despite claims that Amboseli elephants haven't been hunted for 60 years, legal hunting occurred across their range (including Tsavo, Chyulu Hills, and northern Tanzania). Additionally, mass poaching in the 1970s and 1980s drastically reduced their numbers.

While poaching has decreased, human-elephant conflicts have risen.

In 2017, hundreds of people marched in the Global March for Elephants, Rhinos and Lions, yet that same year, one of the "last big elephant bulls in Africa" - 49-year-old Little Male was suspected of killing a farmer and was shot and killed by authorities. He was described as in his prime, fathering calves and passing on his good genes.

In Longido District, Tanzania—where hunting is legal—elephants have killed or injured dozens of people, including children, over the past eight years. As conditions improve on the Tanzanian side, more elephants will move there, increasing human-wildlife conflicts.

Elephants as Ecosystem Engineers

Elephants shape their environment, but only when given large, unrestricted spaces. In Kenya, fences are now necessary to protect trees and biodiversity. Human activity is the dominant force shaping the ecosystem today.

Amboseli's elephants are not representative of all African elephants. Their movements are predictable, and they are protected by 370 Big Life rangers over 1 million acres—protection that is unattainable in most of Africa.

The Role of Trophy Hunting in Conservation

A 2022 study found that 76% of Africa's elephants are in transboundary populations. Some conservationists oppose trophy hunting in these areas, yet Kenya remains unique by banning it entirely.

However, evidence suggests Kenya's 1970s hunting ban accelerated wildlife losses due to increased poaching and habitat destruction. While poaching is now under better control, conflicts between elephants and humans continue.

In the early 1990s, Kenya's elephant population plummeted from 167,000 to 26,000 due to poaching. By 1994, with the human population doubling from 15 million to 27 million, many Kenyans believed there were "too many elephants."

At the time, Joyce Poole—then coordinator of KWS's Elephant Program—ordered the killing of problem elephants, authorizing 124 between 1990 and 1993. Today, she opposes the hunting of five mature bulls, raising questions about consistency in conservation policies.

The Impact of Drought and Habitat Loss

Drought is a major killer of Amboseli's elephants, especially males over 50 and abandoned calves. This triggered the rise of the elephant orphanage industry in Kenya, which tugs on the heartstrings and loosens the purse strings.

Swamplands outside the park have been converted to farmland, and Kilimanjaro's glaciers—vital for Amboseli's water supply—are 85% gone, possibly vanishing by 2050.

Infrastructure developments are cutting off migration corridors. The crucial Kimana Wildlife Corridor is now reduced to just 85 meters wide and 800 meters long.

A 2022 study analyzed 9,182 elephant deaths in Kenya from 1992-2017:

- 31.5% were due to poaching (2,920 deaths).

- 19.9% resulted from human-elephant conflict (1,827 deaths).

Elephants are being poisoned at waterholes, caught in snares, hit by vehicles, speared, and shot, threats that worsen during droughts.

Are the Maasai Truly Living in Harmony with Elephants?

The Maasai have historically speared rhinos and elephants in protest of conservation policies.

In 1977, Amboseli researchers, including Moss and Poole, noted that elephants feared Maasai the most, often fleeing at the sight or smell of their clothing. A 2007 study confirmed this, showing elephants reacted with extreme fear to Maasai garments.

Some tragic incidents highlight this conflict:

- Teresia, a 62-year-old matriarch, was speared multiple times and left to die over 10 days in 1984. As painful as her death was, though, Joyce preferred that over being killed cleanly, efficiently, and painlessly by a bullet.

- Fritz, a 5-year-old male, was found gruesomely speared by a Maasai gang.

Spearing has declined but still occurs, with many bulls suffering from poisoned arrows.

Misinformation in Conservation Narratives

The Humane Society International (HSI) claims to work tirelessly around the globe to promote the human-animal bond and confront cruelty to animals in all its forms.

However, in this video, HSI misrepresents key facts, suggesting that Maasai livestock grazing benefits elephants, yet Amboseli's management plan states that overgrazing is a major ecological threat.

Kenyan authorities have a history of secrecy regarding conservation data. KWS has been accused of illegal ivory sales, and reports on Amboseli's economic impact remain unavailable.

Similarly, the Maasai Mara has seen over 40 lions disappear since early 2024, with suspicions of illegal herding and KWS cover-ups.

Amboseli's Changing Landscape

Amboseli has drastically changed over the past 50 years. In 1979, only 149,000 people lived in Kajiado County; by 2023, the population exceeded 1.2 million. Kenya's total population is projected to reach 85 million by 2050.

In her book, Joyce Poole described the Amboseli elephants, even three decades ago, as existing on "islands in a sea of hostility". She lamented even then that, "Where elephants and people could not coexist, we erected fences, we shot elephants, and we drove elephants out of troubled areas with helicopters and bands of armed rangers."

New lodges and tourism pressures threaten to disrupt communication as lodge generators interfere with elephant vocalizations.

Soon, Amboseli National Park will transfer from KWS to the Kajiado County Council. Conservationists hope wildlife needs remain a priority, but financial interests may take precedence.

Conclusion: A Broader Perspective is Needed

Conservation must address habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, and rising populations. Yet many activists use hashtags like #NotYourTrophy and #EndTrophyHunting, focusing solely on stopping hunting rather than tackling these more significant issues.

"Amboseli" comes from the Maa term Empusel, meaning "salty, dusty place." Just as dust can obscure vision, so too does smoke. Especially the figurative sort generated by various entities involved in Amboseli, who wish to create the illusion that if only Tanzania stopped hunting elephants, they would be "saved."

The winds of change have been blowing increasingly stronger there for decades now. Any future for the wildlife and people of this region will require those 'standing too close to the elephant' to zoom out to see the bigger picture.

Comments ()