The Arrogance of Conservation Policy

By Prof Brian Child

The success of Homo sapiens lies ultimately in the ability to cooperate in bands, clans, tribes, nations, and as a global civilization. We are bound together in common enterprise through uniquely human myths, norms, and rules.

As the only species with the ability to trade, we have created enormous wealth through innovation, specialization, and trade. We are, indeed, Economic Man. But our success lies in the making, following, and enforcing of the rules that shape and enable this collective power.

These formal and informal rules that structure human behavior are known as institutions. We will not solve the intertwined problem of poverty and environmental loss by denying the power of the global economic system.

The question is, rather, can we reshape the rules that govern our interactions with nature to get better outcomes for us all?

Unfortunately, the biological rules of natural selection and evolution do not apply to institutions. Institutions often become stuck in unhealthy configurations, held in a state of non-evolution by the people benefiting from the status quo, for decades, centuries, and even millennia, sometimes to the point of collapse.

As a species, we do not always get these rules right, as evidenced by the violence and inequity in the world, but nonetheless, we seem, slowly, to be moving in the right direction.

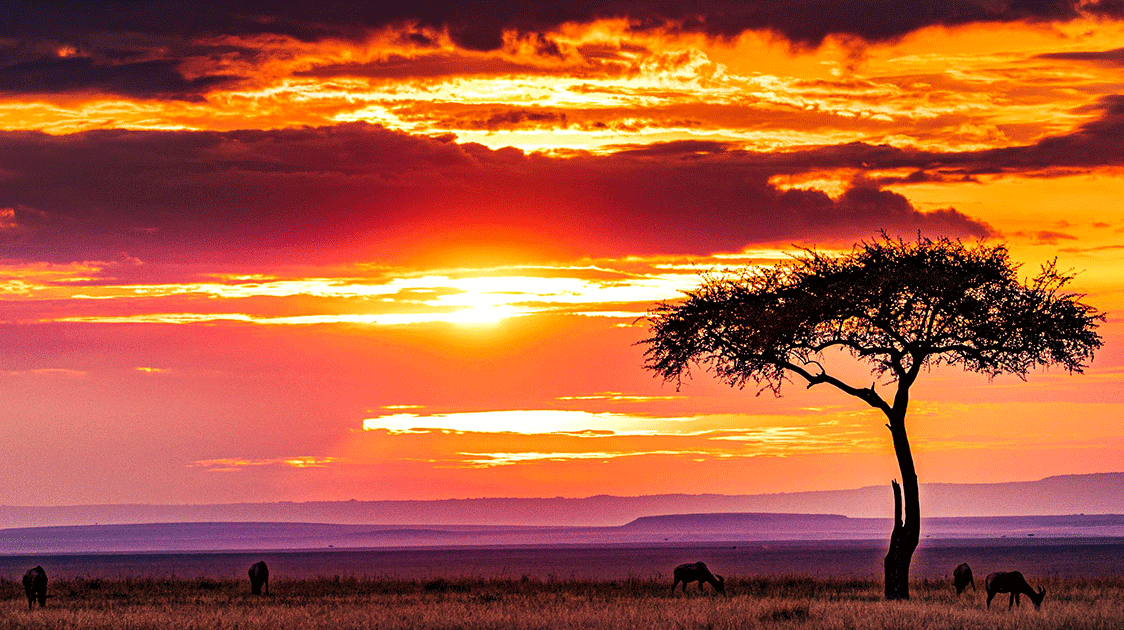

However, at the interface of environment and poverty in forests and drylands, we are patently getting the rules wrong: these systems and the plants, wildlife, and fish they support are depleted, while the people living in them are disproportionately vulnerable to violence, hunger, and deprivation.

The United Nations reports that the forces driving environmental degradation in drylands alone create social instability and even violence and may force as many as 700 million people to migrate to new homes.

This will, inevitably, disrupt the stability of the planet as we know it, and is the direction in which we will continue to travel until we change the current rules and norms.

Wild resources and the people who depend upon them are locked in institutional configurations that evolved on the frontier of the Industrial Revolution, were designed for a different age, and are no longer fit for purpose.

Only by governing wildlife and wild spaces differently, by aligning economic rules and forces in new ways, can we address the wicked problem of poverty and environmental decline. The hope that public ownership and management could control how wild species are used on the private and community lands that comprise 85% of the land area outside protected areas is widely misplaced.

The long hand of the law cannot possibly reach out into all the places where it needs to protect wildlife and is ineffective where it is not welcomed.

Neither will it be accepted until the people who live with wildlife and their age-old livelihood practices of hunting and gathering are legitimized (and modernized) and they have a genuine seat at the rule-making table from which they have been so long excluded.

Without this, we cannot overcome the deep resentment and resistance that outsiders have caused when they impose foreign environmental norms on millions of rural people.

The imperiousness of conservation policy continues to this day; somehow, species like elephants and rhinos are so important that, in deciding their future, we do not need to listen to the opinions and wisdom of the local people and farmers who live with them.

Daniel Kahneman (2011) suggests that we solve problems in two different ways. Usually, we do this by thinking fast emotionally and repeating the patterns we know. And occasionally, by thinking slow, carefully analyzing systems, and inventing truly innovative solutions.

We need to think slow to have an intelligent (slow) conversation, not an ideological one, and to open-mindedly consider that the solution to the problems we share may be very different from our current norms and practices and require very different models, principles, skills, and approaches.

At some stage in our lives, we have all played or witnessed a game where unclear and poor rules have led to conflicts and arguments, turning something that should be fun into a mess.

When rules are fair and clear, by contrast, there is a lot of fun to be had, and you can focus on the game and not the rules or the politics and conflicts surrounding the rules.

The study of rules or institutions is called new institutionalism or institutional economics. It is gaining currency as an explanation for the difference between affluent and vulnerable societies, and some of the best-known economic historians use the theory of institutions to explain why some societies prosper and others do not.

Historically, prosperous societies are rare. Living in an age of unprecedented freedom and prosperity, it is easy for us to forget that, until very recently, the conditions of life for most humans were bleak.

For example, after the collapse of the Roman Empire, the European Dark Ages lasted nearly a thousand years, a period in which human populations, ravaged by war, famine, and disease, hardly grew.

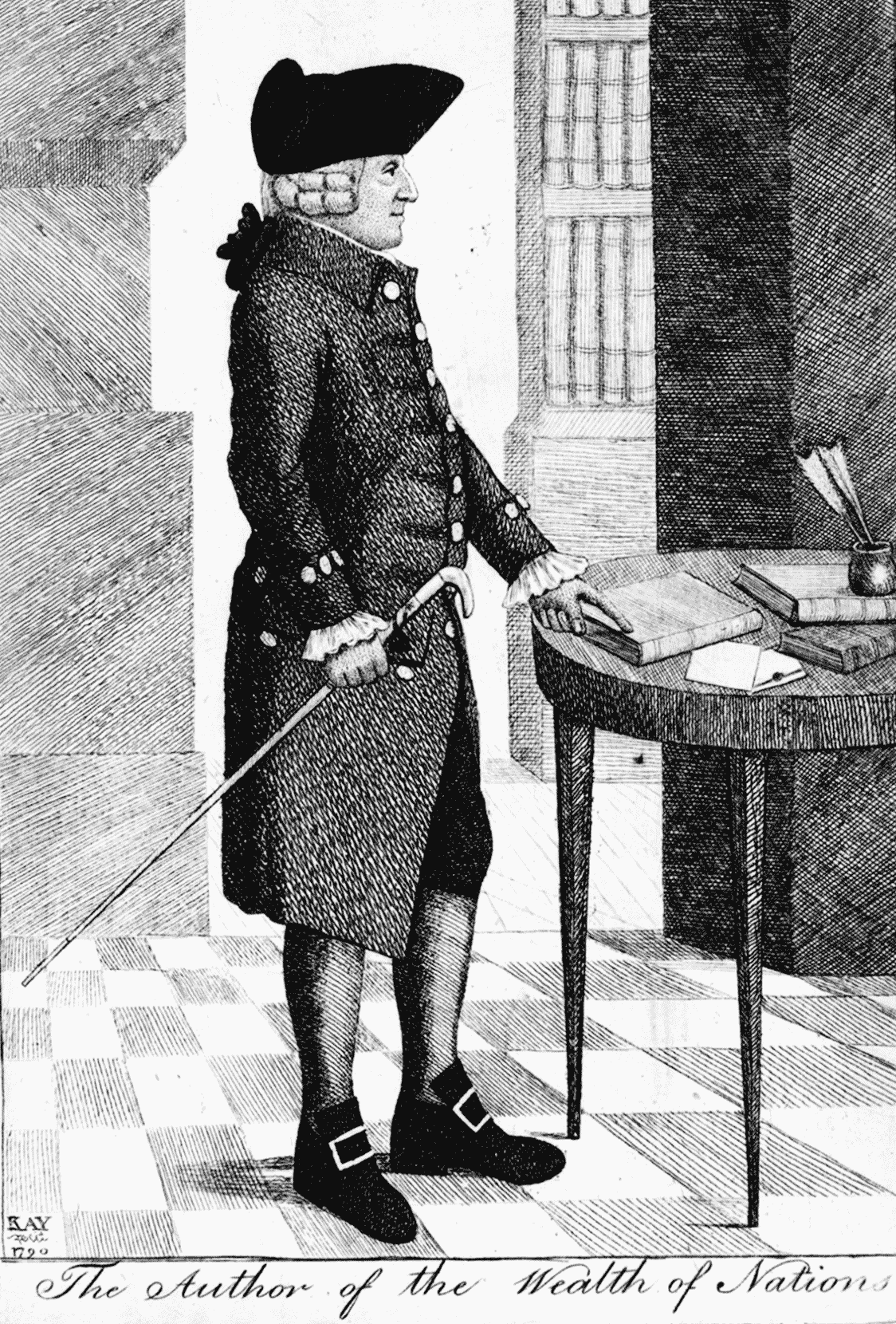

Then, a series of transformations occurred at a critical juncture around the time of the Glorious Revolution in England. These included the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution, and the Industrial Revolution.

The governance of society was radically altered when the rights of man replaced the divine right of kings and when the purpose of property was transformed to protect individuals rather than as a means of extraction by the ruling elite. ‘Warre of every man upon every man’ (Hobbes, 1651) was superseded by the security of person and property, and the way political systems and the economy functioned was revolutionized.

This was the time of Adam Smith. Great wealth was created as value was added to raw materials through the economic processes of specialization, diversification, and exchange.

The Industrial Revolution led to Western society's colonization of much of the planet and ignited the flames of environmental destruction.

Paradoxically, the response to environmental destruction was, in institutional terms, almost the exact opposite of the conditions that led to prosperity. The future of wild resources was placed in the hands of the state, not the people. Wildlife, writ large, became a public good, not the property of the local people who had lived with it since time immemorial.

Indeed, wildlife governance failed to adopt the principles of ownership, self-governance, specialization, diversification, and exchange upon which prosperity was being built.

Rather, leaders like Roosevelt suggested that wildlife was destroyed by human ‘greed’. As powerful bureaucrats, they took the future of wildlife into their own hands and nationalized it, banning commercial uses and taking wildlife out of the marketplace. This laid the foundation for conservation ideology for more than a hundred years.

The underlying problem was incorrectly analyzed.

It was not human greed and markets. Rather, it was the lack of enlightened rules and local controls for channeling and controlling this ‘greed’.

This era also saw the birth of national parks, an idea that has stood the test of time. Parks are an example of effective public management that is well aligned with the needs of society. Parks work – provided that the considerable benefits they provide to society are recognized in sustainable funding and quality management, and where public management is accountable to society.

However, governing wildlife as a public good on private or community land outside parks is an idea that has failed and has failed catastrophically.

The pressures of demography and a global economy shine an ever-harsher light on the underlying deficiencies of the misfit between public goods on non-public land.

Wildlife and wild spaces are being replaced at an unrelenting scale by domestic species and farming, even when this farming is hardly viable, does little to reduce poverty, and is environmentally hazardous.

Over-exploitation also threatens wild species in the absence of institutions to protect them.

Looking back, has taking wildlife out of the economy and placing it under public management been a mistake?

Do we need to take the hard-headed approach of leveraging the high value of wildlife to pay for and protect itself?

And if we do, can we achieve two things at once – reduce poverty by conserving biodiversity and using it wisely?

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)