The Environmental Refugee Threat

By Prof Brian Child

Farming has a massive environmental footprint, and it is difficult to discuss wild species and spaces without some understanding of agriculture. The strength and weakness of agriculture is that it greatly simplifies ecological systems.

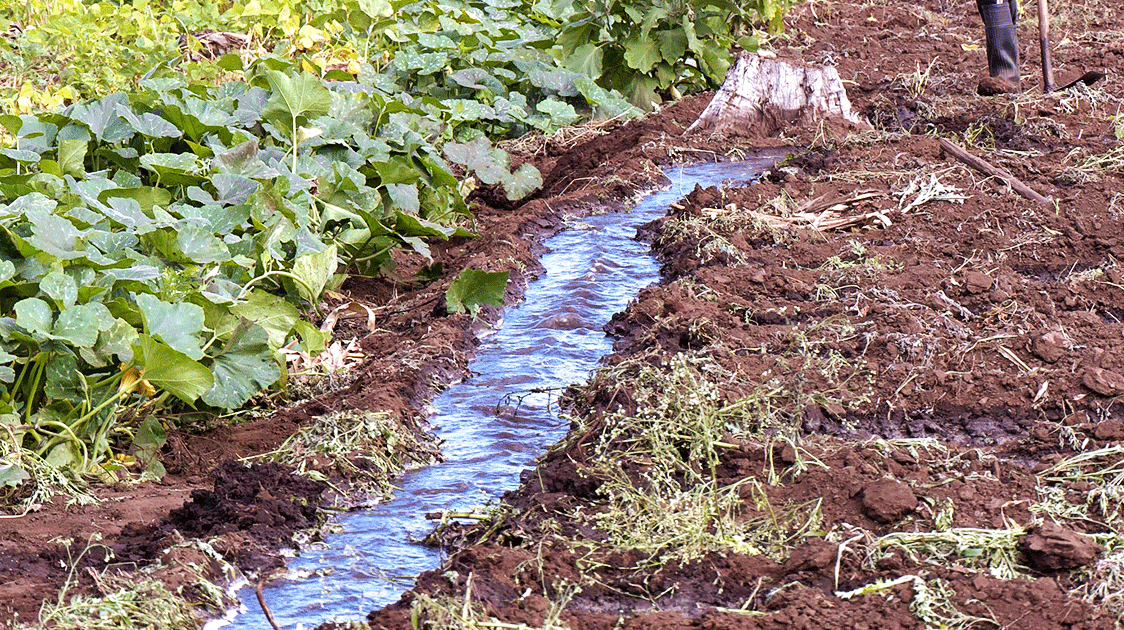

It replaces multi-species ecosystems with crop monocultures or near monocultures and ecological feedback loops with man-made controls through tilling, fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation.

Thus, farming simplifies ecosystems so that it can maximize and concentrate the conversion of light, water, and nutrients into a narrow range of food, fiber, fuels, and other raw materials that are useful to man.

Ecological simplification may work in the agricultural sweet spot – the fertile and well-watered prairies, deltas, and steppes that have been converted wholesale into farms. However, it is not suited to the ecological complexity of dryland and forest ecosystems, especially given the much lower yields here.

Farming in the agricultural sweet spot is a wise use of land – we must produce food and do it where agriculture is economically more productive than other land uses.

Interestingly, we often justify conservation to protect the original biodiversity for insurance and option values. Yet the agricultural landscapes where many of these important species presumably preside contain few protected areas and are seldom incorporated into maps of biodiversity hotspots (Myers et al., 2000).

Implementing community wildlife management requires a good understanding of the complicated relationship between people, farming, and nature, especially in the 21st century when we need to feed over 7 billion people, with the expansion of agriculture the primary threat to intact drylands and forests.

The relationship between people, farming, and food is complex and emotional and differs greatly on different continents, with no easy answers. About 11,700 years ago, man emerged from the Ice Age (the 2.5-million-year Pleistocene) into the warmer, wetter Holocene and began domesticating plants and animals in the mid-to-late Stone Age.

Most early civilizations occupied the ‘agricultural sweet spot’ – the Nile Valley and Fertile Crescent, the Indus and Ganges Valleys, and the Yellow River Valley – where there was sufficient (and sufficiently reliable) water and soil fertility to grow crops consistently.

Farming has also allowed profound societal changes, not always for the better. The pastoral vision of farming as a comfortable lifestyle is far from the truth. Historically, farmers may have delivered a food surplus but were often worse off.

Farmers worked harder than hunter-gatherers, their diets narrowed towards grains and carbohydrates, disease was more prevalent, and farmers became shorter, less healthy, perhaps less happy than egalitarian bands of hunter-gatherers, and trapped at the bottom of hierarchical societies (Diamond, 2002; Fukuyama, 2011).

Even today, small-scale farmers are often trapped in a life of drudgery, with marginal and hard livelihoods (Harari, 2014), and prone to food insecurity and disease.

Even now, the term ‘agricultural development’ remains an oxymoron. Farming is important because it provides food and is a major activity for the poor.

These are not the same things.

Most of the planet’s food comes from high-input farming, and the low-input farming that does so much environmental harm can hardly feed the people who do it.

Historically, peasant farmers seldom prosper or gain political freedoms, and countries have rarely advanced to modernity by tilling the soil – consider the challenges faced by the peasants in feudal Europe and the vulnerability of contemporary farmers in the tropics.

Farming places severe pressure on land and wild resources, utilizing nearly 40% of available land by the end of the 20th century (Foley et al., 2011).

Croplands comprised a third of this area, and the global cropland area doubled every century after 1500 (Goldewijk et al., 2010).

A further third of the planet comprises hot and cold deserts. Despite the increasing scarcity of farming land, land degradation affects 38% of the world’s croplands, or 2 billion hectares, and is particularly serious in the drylands in poor countries (Rekacewicz, 2005).

Not surprisingly, the major threat to nature is the plough and the cow, as the space for nature is squeezed. Using species-area curves, Wilson (2016) calculates that today’s protected areas, which cover 15% of the planet, will conserve roughly 62% of species, but we need half the planet to save 84% of species.

Croplands expanded by 35–80% between 1961 and 2013 (FAO, 2009; Deepak, 2016), mainly at the expense of forests and drylands in poor countries, including Africa.

In Africa, farming yields have remained stagnant at about 1 ton per hectare (Sanchez, 2015), so food production depends on clearing more land; croplands have expanded by 50% since 1960.

These forces farming beyond the prime agricultural zone and into forests and drylands where it becomes a major threat to surviving wildlife and habitats, a situation that will worsen, even to the point of catastrophe, as the African population approaches 2 billion people in the next few decades.

African farms and the environment are already not coping (IPBES, 2018), yet 54% of global population growth will be in Africa (and 82% by 2100). Apart from Africa, most population growth will be in South Asia and Central America, where agricultural expansion is also a significant threat to wild habitats (20% expansion).

By contrast, croplands are retracting in North America, the European Union, and Eastern Europe (FAO, 2009). We are dealing simultaneously with several problems – feeding the world, rural poverty, and space for wild animals and places. These challenges deserve far more intellectual attention.

Most of the world’s food comes from high-yield and industrial agriculture, and we have the technical ability to feed the world. The agricultural expansion that is so damaging to forests and drylands is mostly through low-input farming by extremely poor people who, paradoxically, are often hungry.

Low-input farming in agriculturally marginal areas is not sustainable and will have severe human and environmental effects, not least in projections of 50–700 million environmental refugees (IPBES, 2018).

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)