What Price Wildlife?

By Prof Brian Child

There is no doubt that intact natural systems and wildlife are in serious trouble. Man’s impact on the planet is summarized by an article in Science in 2011 entitled ‘A Global Perspective on the Anthropocene’. People and farming have expanded into most corners of the globe, mostly in the last 100 years.

Over 90% of total mammalian biomass is now made up of humans and domestic animals compared to under a tenth of 1% at the dawn of agriculture 10,000 years ago (Smil, 2002).

This trend is accelerating. Since 1900, the zoomass of domestic herbivores has increased more than fourfold while that of wild herbivores has halved to only 4% (optimistically); some 50,000 cattle get added to this inventory each day (Ripple et al., 2015; Smil, 2011).

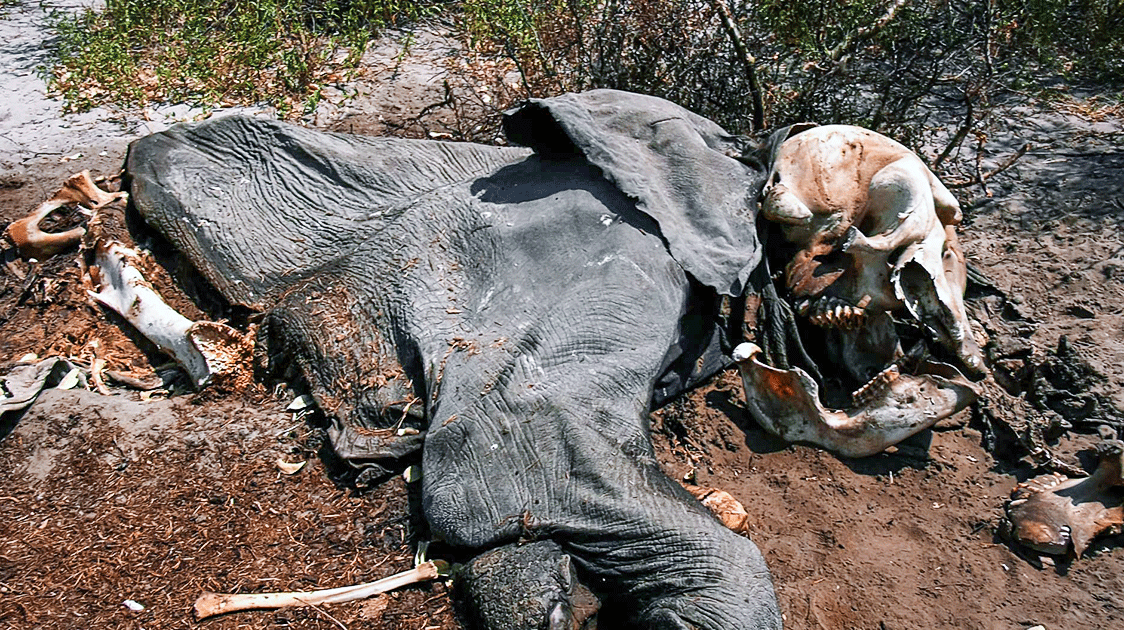

The decline of Africa’s long-surviving wildlife is catastrophic. We have lost well over half of Africa’s wildlife since 1970 inside parks (Craigie et al., 2010) and a great deal more outside (Ogutu et al., 2016), and perhaps as little as 5% of these vast herds survive today.

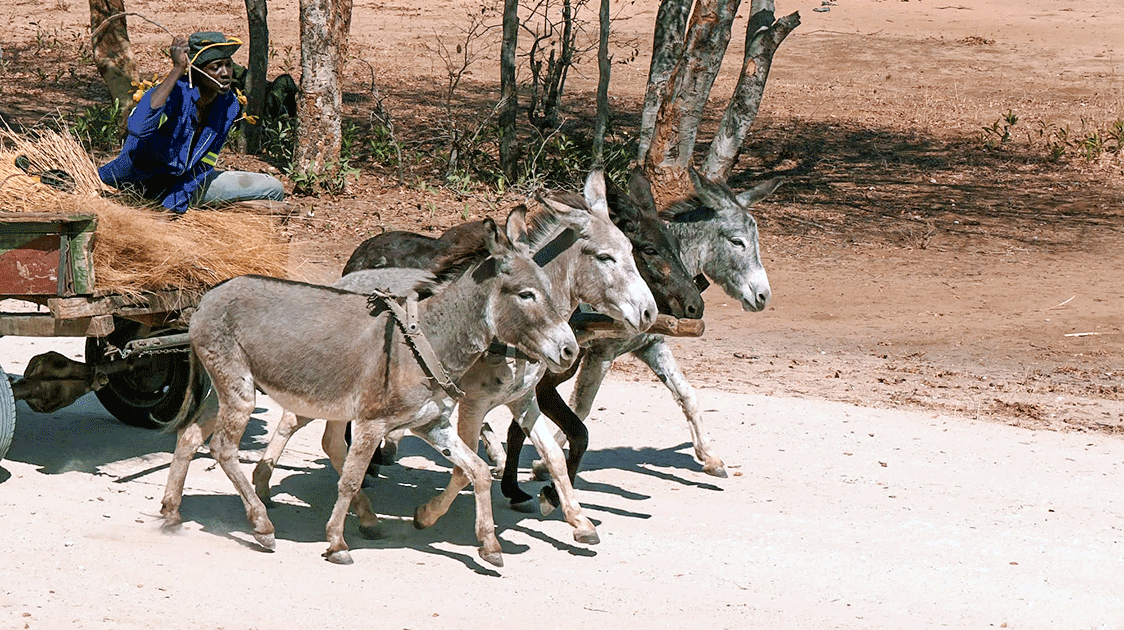

Three major drivers are eliminating wildlife: the cow and the plough, overutilization (bush meat harvesting and the illegal wildlife trade), and conflict (Ripple et al., 2015).

With the media sensation associated with poaching and trade bans, we seldom pause to note the deep economic inconsistencies in these outcomes. The cow and the plough replace wildlife because it has little or no value to landholders.

On the other hand, wildlife is over-exploited through uses such as the bush meat trade and the illegal wildlife trade because it is too valuable.

Which is it?

Failure to analyze the problem carefully leads to incoherent solutions based on erroneous assumptions, such as wildlife bans and demand reduction, which have almost totally failed.

The no-value versus too-valuable conundrum is a critical puzzle we must solve. Solutions based on the secondary matter of price will remain futile until the primary issue – wildlife ownership – is resolved.

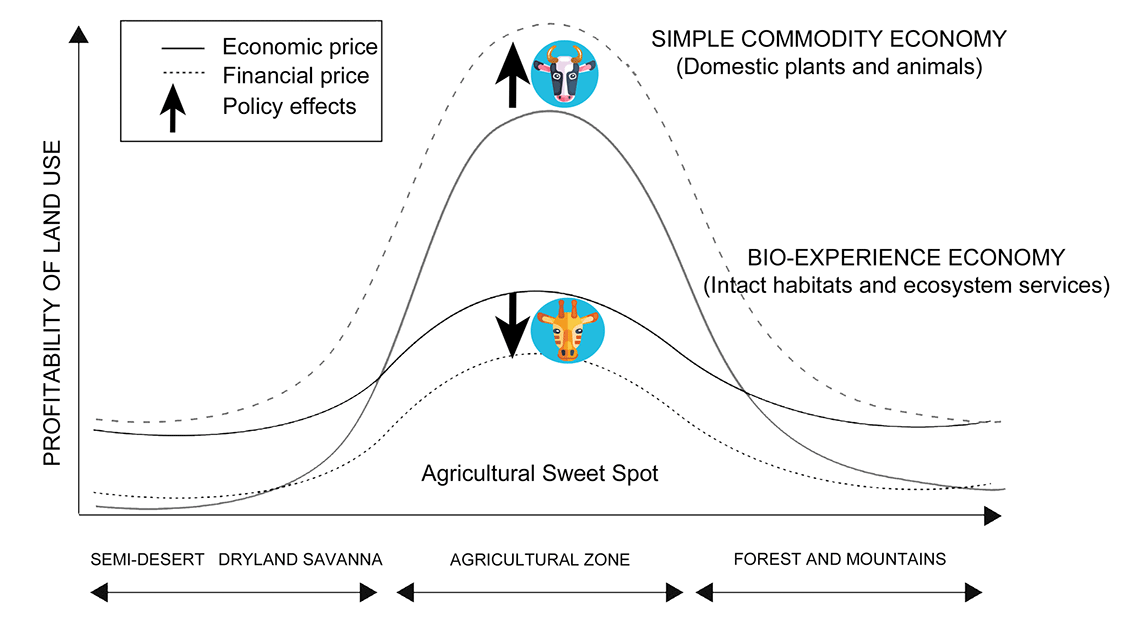

If the previous arguments hold, intact wildlife systems often have a comparative economic advantage in drylands and forests.

This is illustrated by the solid (economic) lines in the diagram above. However, the property and pricing ‘failures’ illustrated by the black arrows favor domestic species and disadvantage wild species, so landholders produce the wrong things.

The solid curves show how land should be allocated, and the dashed curves show how land is allocated after policy failures have distorted underlying prices.

Therefore, farming expands even where it does not make economic sense and replaces wildlife. This also exacerbates poverty because it is economically less efficient.

The alternative future lies in getting these prices right so that land is allocated according to the relative positions of the economic (solid) curves.

This pathway to sustainable poverty reduction requires local people to have strong rights to utilize wild species and intact natural habitats as profitably as possible (rather than converting them to agriculture), maximizing the value of wild species by trading them globally and correcting for missing markets such as ecosystem services.

This is not a binary farming-versus-the-wild argument. Both are necessary, but we can improve the productivity and sustainability of drylands and forests by lifting the financial curve for wild resources upwards to reflect the total economic value better and ensuring that wild resources are competitive.

This is not a pipe dream.

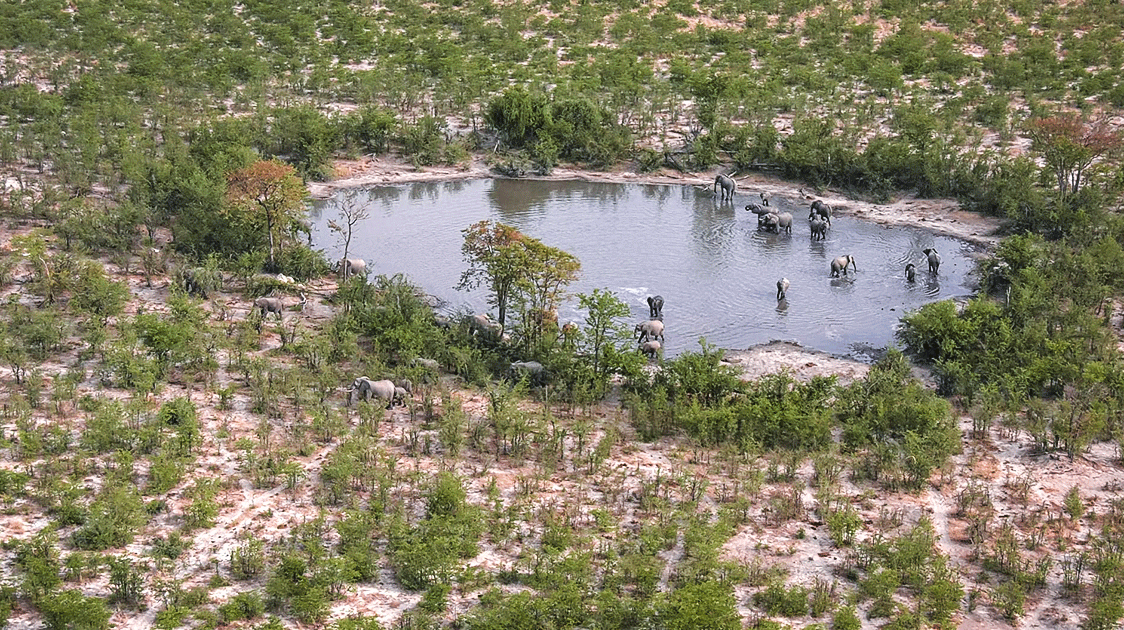

Models like the wildlife economy in southern Africa provide an empirical example of the proactive policy reforms needed to rewild domesticated landscapes.

Theoretically, wildlife landscapes have economic advantages, and terms of trade are moving against raw commodities and agriculture and towards the bio-experience economy, so these advantages are increasing.

However, leveraging the wildlife economy to address poverty and biodiversity losses will require bold institutional reform based on new assumptions about the drivers of poverty and biodiversity.

There will be no progress without effective local ownership of wildlife and wild lands, effective community governance, and active promotion of new and global markets for wildlife.

These new ideas began to emerge under the name of ‘community-based’ solutions in the 1970s as a response to the threats to forestry, fisheries, and wildlife in Africa, Asia, and America.

(Prof Brian Child is an associate professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida and the Life Through Wildlife Project director. His book, “Sustainable Governance of Wildlife and Community-Based Natural Resource Management”, is available on Amazon.)

Comments ()