Sizable Portions – Who's Really Eating Away at African Conservation Efforts?

By Hank's Voice

On 25 January 2024, the Belgian Parliament voted to prohibit the importation of legally obtained hunting trophies from threatened and endangered species, claiming some of them could be further imperiled unless trade is limited.

They, along with Humane Society International (HSI) and other anti-hunting/anti-sustainable use/animal rights organizations, hailed this decision as a monumental triumph for wildlife conservation and animal welfare.

The executive director of HSI/Europe even bragged, "With this decision, Belgium positions itself as a leader in protecting biodiversity and endangered species." Bravely marching on to "save" wildlife, they will try coercing France next, and other European Union (EU) countries, ultimately, to adopt similar bans.

But before they claim that the LEGALLY hunted, highly regulated, INEDIBLE "trophy" parts of wildlife are the problem, they should gain firmer control over the ILLEGALLY and indiscriminately obtained and trafficked EDIBLE parts of wildlife entering their countries daily, in concerning quantities.

Not by much-maligned "trophy" hunters but by other residents of their lands, who are engaging in or supporting bushmeat poaching activities, often knowingly and on a commercial scale, with seemingly no regard for its adverse effects on conservation.

The EU prohibits the importation of any meat and meat products unless they are specifically authorized, certified for commercial consignments, and presented with correct documents.

Important reasons for this include potential disease transmission to humans and animals (both wild and domestic) and potentially threatening the continued existence of wild species or populations by their UNREGULATED take for bushmeat purposes.

These restrictions are not new.

Yet what persists and is thought to be growing in the EU, particularly in Belgium and France? A thriving, organized, luxury bushmeat market. And what is a major threat to wildlife globally, particularly in the tropics, specifically in Western and Central Africa, regions of incredible biodiversity?

The poaching of wildlife for bushmeat.

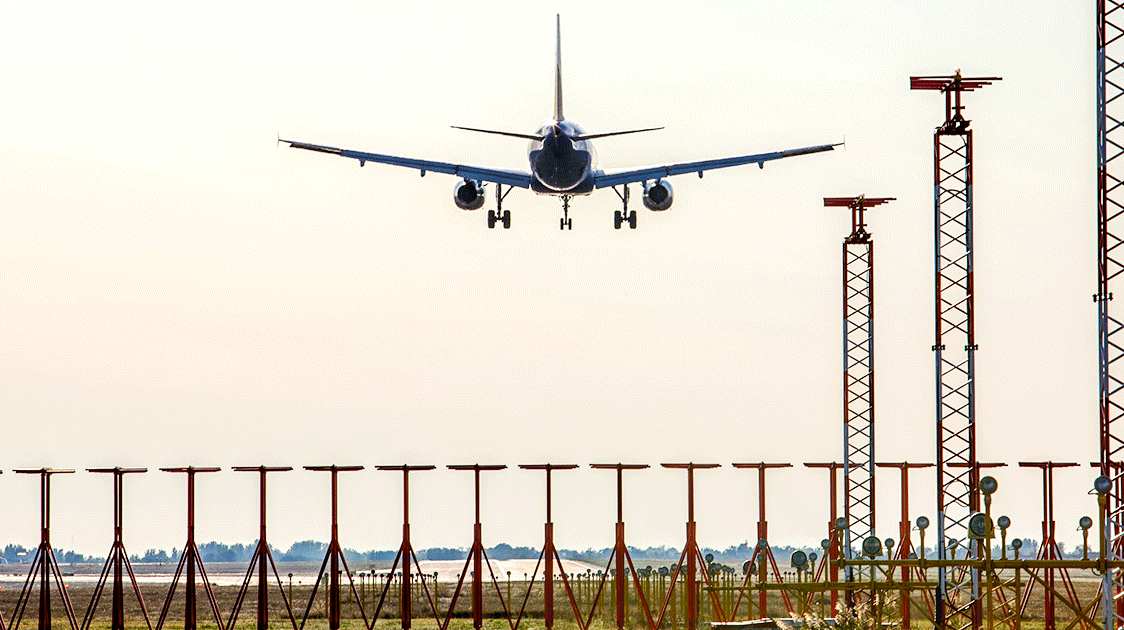

Although it is unfortunately not as well-documented as it should be, there is a growing body of scientific papers reporting that alarmingly large quantities of bushmeat are being illegally brought into the EU via airplane passengers, cargo shipments, and the postal system.

And not just for personal consumption; it also supplies clandestine markets and restaurants in big cities, such as Paris and Brussels. Bushmeat is often sold there at the top range of prices of premium domestic livestock and legally obtained wild game.

And CITES-listed species (threatened or endangered) are amongst those sold and consumed, with many species mislabeled.

Yet expat urban elites consider bushmeat a delicacy and a way of retaining cultural ties to their homelands.

Efforts to document and estimate the extent of the bushmeat problem began in 2006, when Justin Brashares of the University of California at Berkeley recruited volunteers (expats from Western African countries) to visit illegal markets in Paris, Brussels, London, New York, Montreal, Toronto and Chicago, resulting in evidence of greater than 6000 kg (13,227 lbs) of bushmeat moving through these seven markets each month.

A 2008 study by Chaber et al., estimated that 5000 kg (11,023 lbs) of bushmeat each week were illegally transported in personal baggage through Paris's Roissy-Charles de Gaulle Airport, contributing to a whopping 273,000 kg (601,862 lbs) annually, on Air France carriers alone.

Assuming the detected rates were truly representative, as they could actually be higher. Seven percent of passengers searched were carrying bushmeat in quantities of 20 kg (44 lbs) on average, ranging up to 51kg (112 lbs).

The most recent data comes from Belgium, in a 2017 – 2018 study by Gombeer et al. The very first of its kind on the clandestine bushmeat markets in Brussels.

Travelers responding to a survey and vendors, upon questioning, indicated that they knew bushmeat was illegal and why. Yet they were willing to risk transporting and selling it to stay connected to their countries of origin, to enjoy preferred food items, and to benefit financially.

Some even earned enough to pay their travel expenses, which are typically significant. Some Brussels vendors admitted having stores and customers in other Belgian cities and providing phone numbers to their customers to check on when the next shipment would arrive. The average interval was one to two weeks, and prices ranged from 31 – 62 euros/kg (15 - 30 USD/lb).

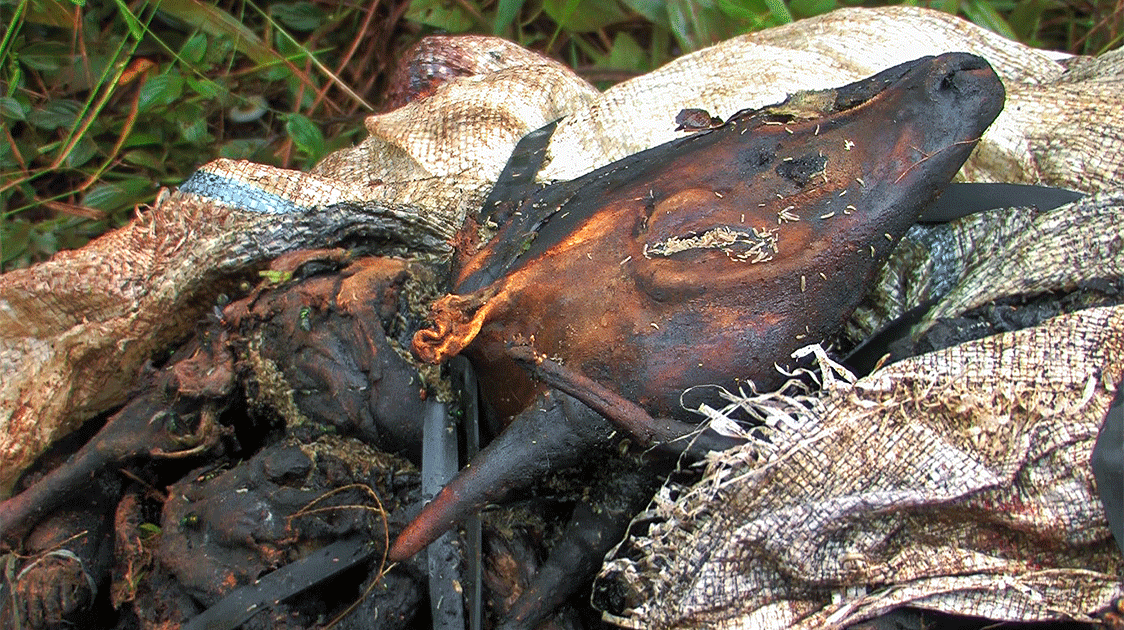

Trafficked bushmeat was typically smoked, dehydrated, or in pieces difficult to discern its species origin from visual inspection alone. Vendors typically claimed samples bought at markets to originate in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Because morphological identification of 15 purchased pieces was impossible, DNA barcoding of mitochondrial markers was used to attempt identification.

Seven of the 15 pieces couldn't be identified to species level. Eight (including three monkey samples) did not correspond to the vernacular name given by vendors.

Three belonged to a different family than the vendors claimed. Three were inaccurately labeled species at the genus level. AND…. four were from CITES-LISTED species: red-tailed monkey, De Brazza's monkey and blue duiker.

Two others simply identified to the duiker level, with no distinction possible between species. Important inadequacy since some duiker species are listed or data deficient.

It is important to note that such challenges with identifying species do not occur with hunting trophy imports, as they are more wholly discernable, readily identifiable parts of which there is much knowledge, as the regulated trade has been legal and highly monitored for a long time.

All bushmeat in these European markets is illegal at the national, EU, and international levels.

So, we do not fully comprehend the actual scope of the problems it creates within and between multiple continents and countries.

But we DO know that the illegal bushmeat trade is absolutely a KNOWN major contributor to the overexploitation of vulnerable and protected species in Western and Central Africa.

Species struggling to exist in, and often endemic to, some of the world's most biodiverse regions. The take of these animals is indiscriminate, as the goal is to obtain meat.

All ages and both sexes are made of meat. No need to be selective. With no regulations, there is no accountability. And there are no incentives to use these resources sustainably.

These areas are hammered by habitat loss due to deforestation and land conversion, terrorism, and exploding human populations.

Their big predators are rapidly disappearing or have already extirpated due to the loss of their prey base and increased human-wildlife conflict.

The bushmeat trade is bad enough in its countries of origin, negatively impacting wildlife populations and the ecosystem services they can provide.

But in many cases, especially in countries that offer no legal hunting, it is sadly one of the few options for local human populations to obtain meat.

The international bushmeat market, for personal consumption or sale in EU countries' luxury markets or restaurants, is infinitely more inexcusable and should not be tolerated.

Yet what does Belgium and HSI purport to be a threat to biodiversity and animal welfare instead? Belgian hunters LEGALLY imported the undeniably relatively paltry purported 308 trophy parts between 2014 and 2018.

It is critical to note that this number may not even represent 308 individual animals, as trophy imports are often counted as separate parts of particular animals, i.e., an antelope's skull equals one trophy, plus its skin equals two trophies.

It is also essential to note that a country exhibiting more honest concerns about conservation (the USA) has developed a permitting system for listed species that requires either non-detriment or enhancement findings to import these hunting trophies.

And this information is indeed available and presented by hunting operators regularly.

Inedible animal parts obtained via legal hunting have been proven to be a proper conservation tool in a myriad of ways, globally, that can sustainably provide valuable food resources, legally, for residents, yet the push continues to ban them.

That's anti-conservation.

It's a true shame that Belgian politicians mistakenly thought HSI's cause du jour was of substance. France, however, is a country well-known for its discerning cuisine, so hopefully, when it comes to conservation matters, it will thoroughly scrutinize what the misguided misinformation campaigns to ban trophy hunting imports are attempting to serve on its plates.

Allowing bushmeat to continue to illegally enter the EU whilst proclaiming legal trophy hunting imports are the real threat to biodiversity, should not be on anyone's menus.

It is fare that is unfair to all those who truly do care about nature's future and its connections with humanity too.