Why do Southern African Conservationists and Communities Support Hunting?

By Prof Brian Child

The spread of Western civilization was synonymous with the spread of domestic species and the domination of nature, often with deleterious consequences (Monbiot 2022).

Importantly, the economic superiority of domestic species did not drive this, but because, for deep historical reasons, farmers owned livestock but were denied these rights to wildlife (Bowles and Choi 2013, Child 2019).

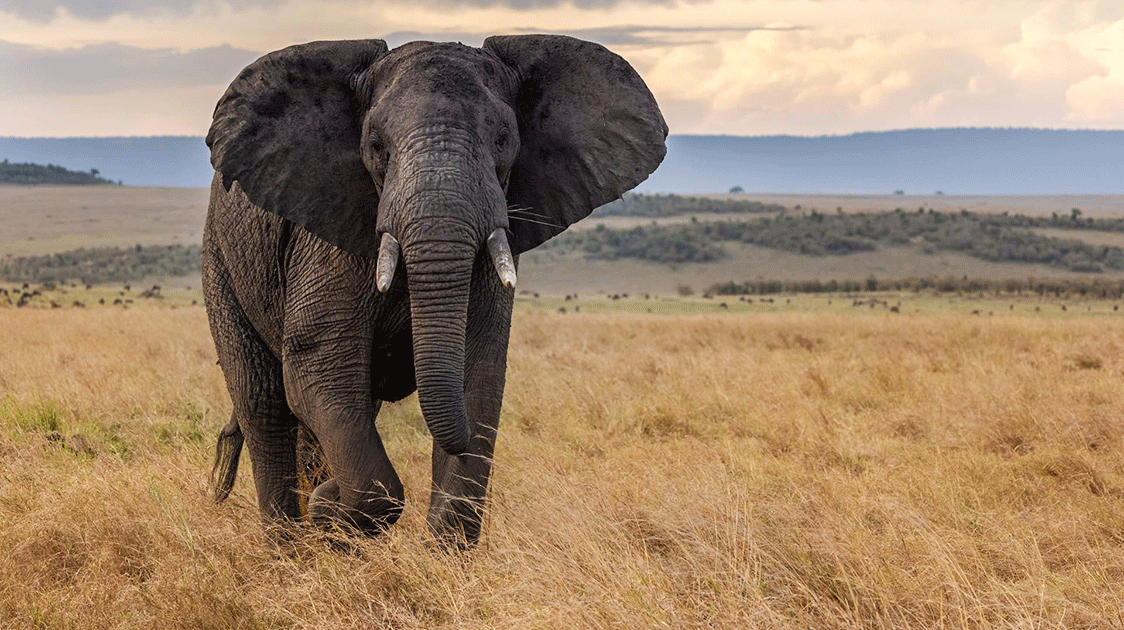

By the 1960s, it was clear that livestock were eliminating wildlife across southern Africa (Pringle 1982) while also causing environmental degradation, including soil erosion, bush encroachment and the destruction of wildlife. Wildlife administrators hypothesized that wildlife would provide superior land use (Riney 1960, Bigalke 1966).

To test this, they changed the legislation to allow farmers to own wildlife (Child 1995). Their objective was never to impose a conservation agenda on farmers and working lands.

They knew this would backfire.

They aimed to open up economic opportunities, reducing as much as possible outdated regulations and restrictions on wildlife.

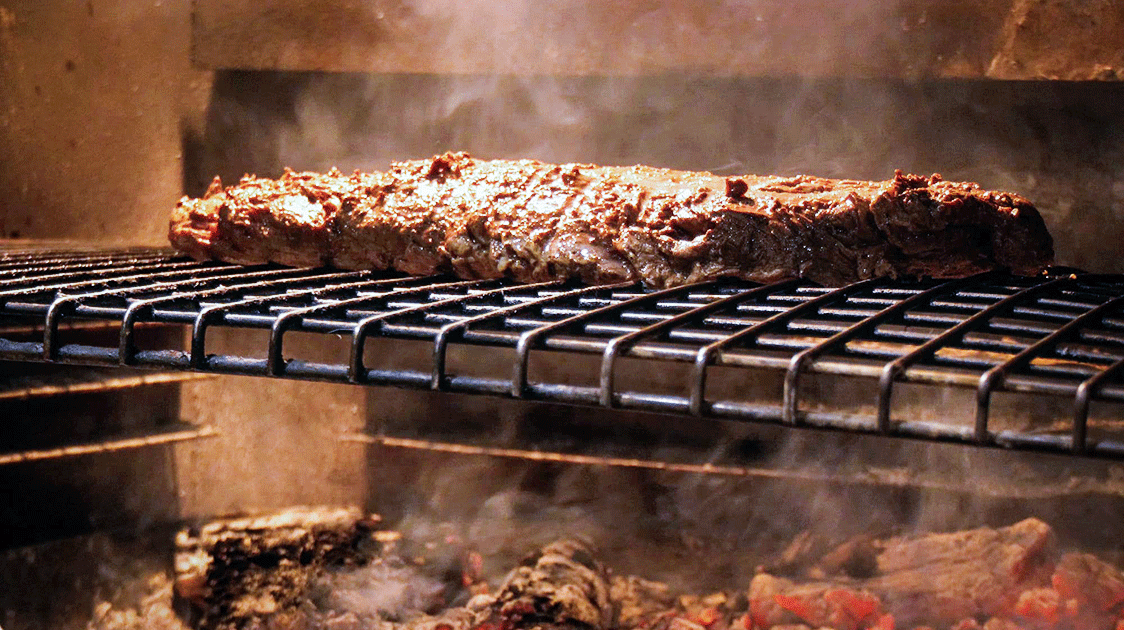

Scientists anticipated that game would produce more and better meat than livestock (Talbot, Payne et al. 1965, Roth 1966). To this day, game meat remains a by-product of other forms of wildlife utilization (Walker 2012), reflecting our argument that dry savannas are suited to a bio-experience economy and not to commodity production.

Starting in the 1960s and 1970s, farmers were permitted to harvest small numbers of wild animals surviving on their lands, usually browsers like kudu, which survived livestock over-grazing. Game meat was not profitable, and there was no market for hides and skins.

However, farmers noticed a big bump in their paychecks from hunting a very small number of adult male animals on mini hunts. They incrementally reduced cattle to make space for more wildlife and brought back species wiped out by farming.

Wildlife and hunting saved some 15,000 ranchers in Southern Africa from financial and ecological bankruptcy.

Hunting was never the objective of bold wildlife legislative reform or, indeed, of landholder motivations.

Making a living was.

It just so happened that high-fee hunting emerged as the most powerful tool for rewilding, financing some 70% of wildlife and wild lands in Southern Africa.

The farmers make a living by returning their farms to nature through hunting. These working lands are not public conservation areas.

Wildlife conservation is the unintended dividend of unlocking the economic potential of wildlife and is measurably the world’s greatest conservation success of the past five decades.

(Prof Brian Child is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida.)

Comments ()