Why Are There No Quotas on Domestic Livestock?

By Prof Brian Child

The purpose and importance of quotas—a form of regulation that costs the landholder or community some degree of sovereignty—needs to be analyzed.

Where wildlife proprietorship replaces a tragedy of the commons, quotas set in distant administrative capitals serve no purpose; they are administrative window dressing that invariably does more harm than good.

Centralized decisions are usually less informed than local ones, while quotas serve to truncate the rights and sovereignty of farmers and communities, who often value rights over wildlife as much or more than financial benefits (Louw, Pienaar et al. 2021, Merz, Pienaar et al. 2023).

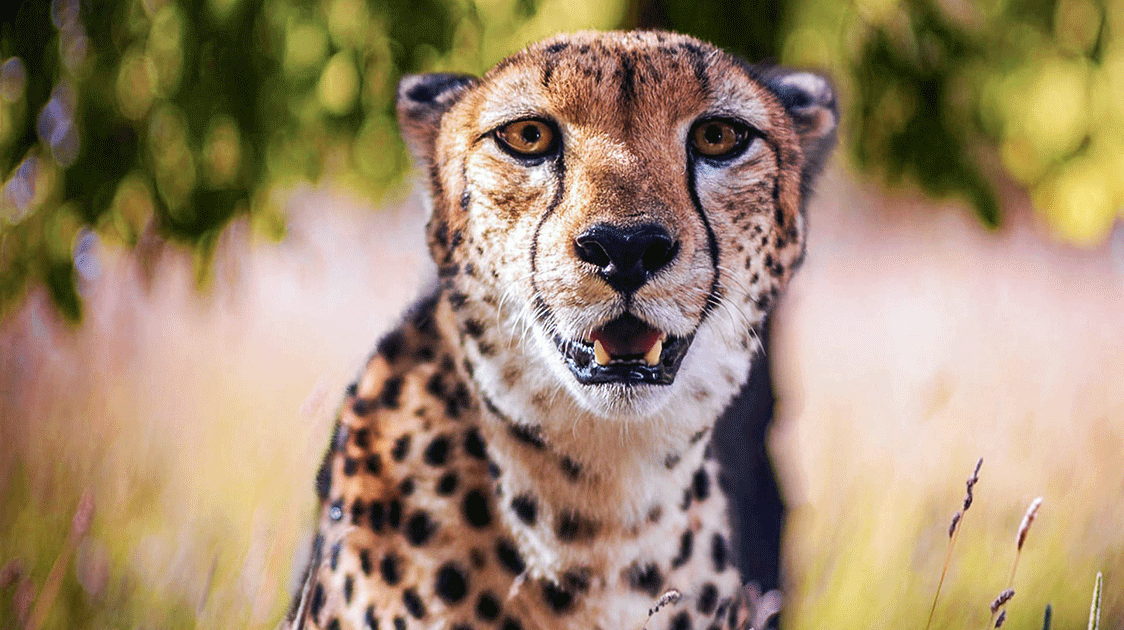

This is partly why farmers in Namibia and Zimbabwe manage leopards judiciously but shoot the ‘governments’ specially protected cheetahs on site; it is true that cheetahs kill livestock indiscriminately, but farmers stopped killing cheetahs in Zimbabwe once they had the right to utilize them, even when they did not exercise these rights (Child 1995).

Note also that when Zimbabwe’s Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975 signaled confidence in wildlife ranchers by devolving proprietorship and eliminating all quotas in favor of collective self-regulation (Child and Child 2015), Zimbabwe’s wildlife population increased more than fourfold on private land (Booth 2002).

As predicted by Ostrom’s theories, devolved self-regulation was low-cost, highly effective, and had far fewer instances of abuse than top-down systems.

Further, the wildlife authorities recognizing that quota permit systems were outdated, inefficient and costly to the sector.

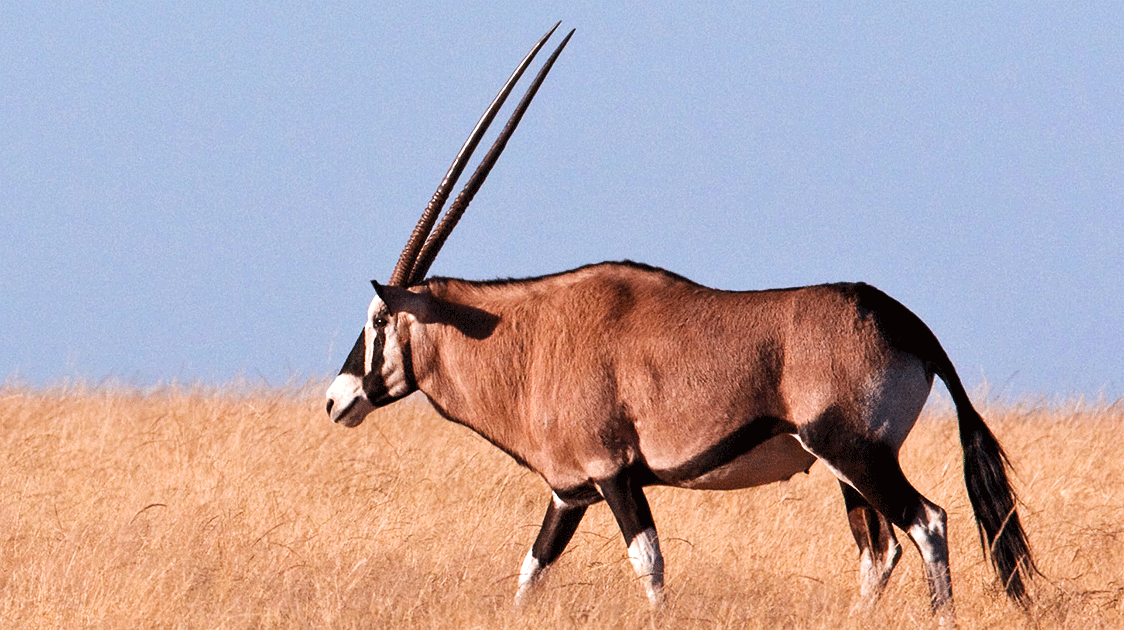

The persistence of quotas is an interesting phenomenon. They are never applied to domestic species by ministries of agriculture, where the culture is to facilitate farming.

Quotas are a form of aborted devolution (Murphree 2002). They reflect a culture of top-down control rather than one of industry facilitation and landholder empowerment and provide administrators with leverage that can be used for good or ill.

When conservationists bray for animal counts and stricter quotas, they completely underestimate the system's checks and balances.

If quotas are necessary, the underlying problem is invariably policies that hold wildlife in an open-access status, and the solution is to address this problem.

Born out of the norms that wildlife is an open-access resource, the technical understanding of quotas is also deficient; the knee-jerk requirement for animal counts and stricter quotas reflects a scarcity mentality, misunderstands that hunting adult males has almost no direct consequences for wildlife populations, misses the point that trophy quality and adaptive triangulation provide a technically and financially superior approach to setting quotas (Taylor, Bond et al. 1997), and under appreciates the checks and balances in the system.

Top-down quota setting usually results in wildlife being undervalued.

(Prof Brian Child is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography and Center for African Studies at the University of Florida.)